A Prospective, Single-Blinded, Bicentric Study, and Literature Review to Assess the Need of C2-Ganglion Preservation - SAVIOUR’s Criteria

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Joint manipulation for craniovertebral junction instability is often hindered by the C2-ganglion (C2G). Our study aims to compare the surgical outcome among patients with or without C2G preservation and discuss the technical nuances.

Methods

We did a prospective, bicentric study and included all the operated patients with craniovertebral junction anomaly. The outcome was assessed by the Pain Numeric Rating Scale, Patient Satisfactions Score, and Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale. The fusion was assessed using Lenke fusion grade.

Results

One hundred seventy-one patients (88 in group A and 83 in group B) were included. The most common symptom was spastic quadriparesis (n = 165, 96.5%) with median Nurick grade 3.3. Thirteen patients had suboccipital numbness and 12 patients had paraesthesia. Mean blood loss in group A was 490 ± 96.2 mL and group B was 525 ± 45.7 mL; median operative time was 217.9 and 162.2 minutes in the groups A and B, respectively (p < 0.05). At the follow-up (median, 46.8 months), Lenke fusion grade A was achieved in 92.4% and grade B in 7.6%. A trend suggesting better functional outcomes (numbness, parestheisa, scar outcome, and postoperative ulcer formation) in group A was seen with all 6 patients, who underwent O-C2 fixation, developed pressure sore.

Conclusion

Our results support ganglion preservation, especially in the subset of patients where occipital plating is required. Although the study fails to show any statistical significance, we suggest that one should always start with an ‘intent’ of preservation as the functional outcome is better.

INTRODUCTION

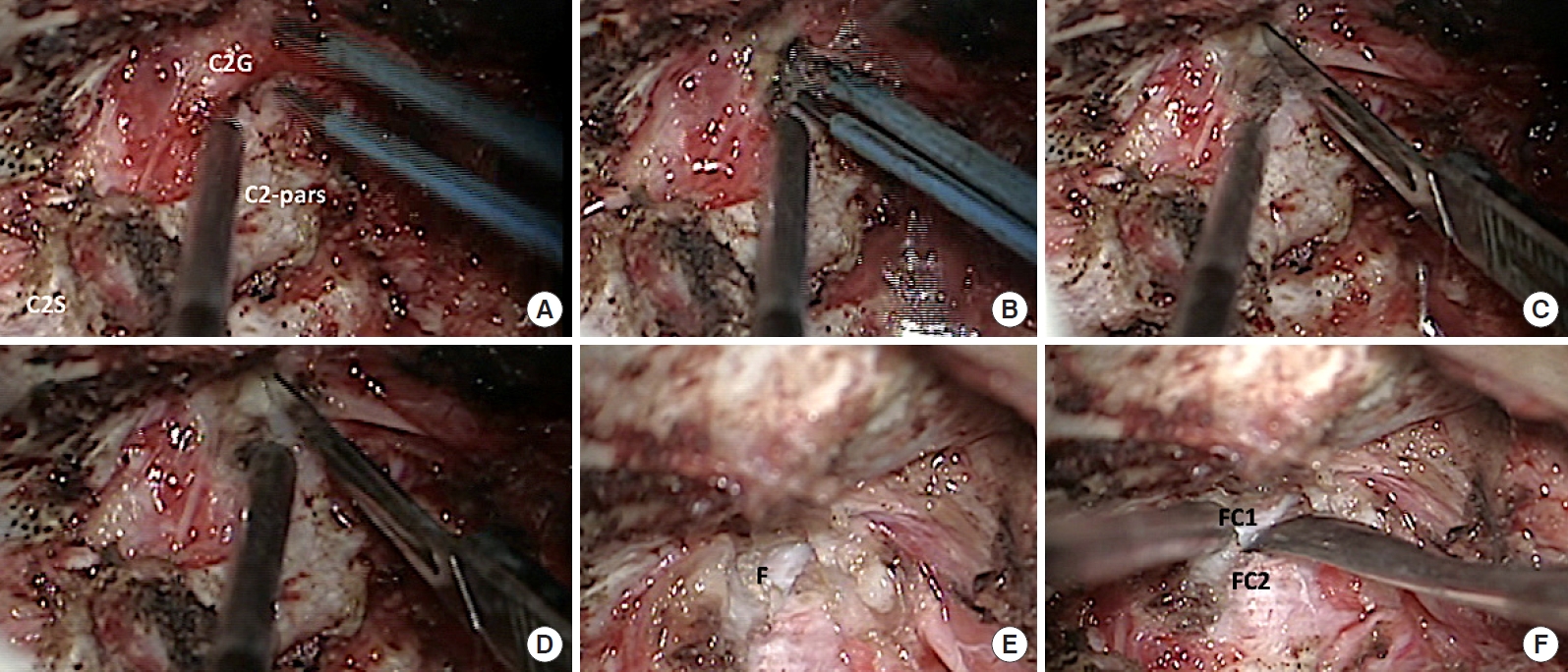

Posterior fixation is one of the most popular techniques for craniovertebral junction (CVJ) instability. Posterior fixation with suboccipital plate (O) to lateral mass of C1 (C1L) and pars interarticularis of C2 (C2PI) or C1L to C2PI has both short-term and long-term reliability, but have certain inadmissible drawbacks, of which, need for C2G preservation remains an obnoxious controversy. Opening the joint, preparing it, and then accommodating bony chips or spacer promises a better fusion rate [1-3]. The joint manipulation is hindered by C2-ganglion (C2G) and venous plexus around it (Fig. 1A-F). If one has to decide among adequate joint manipulation or C2G preservation, anyone will opt to C2G-sacrifice, to meet good visualization and undisrupted anatomy. Literature shows that the quality-of-life remains unaffected except for minor numbness but an acceptable recommendation is still warranted [4]. In our study, we want to highlight the fact that an “intent” to preserve C2-root/ganglion (C2G) is missing amongst surgeons, in order to gain advantage of a wider exposure. Formerly, when rod-and-screw technique was described, the surgeries were performed under direct vision, so the need for wider exposure was in demand. However, with the advent of optics and high-end microscope and endoscope, there is a paradigm shift towards minimally destructive surgery. The study aims to compare surgical outcome in patients after C2G preservation and discuss the technical nuances of procedure. We have also highlighted some factors (SAVIOUR’s Criteria) which help in decision-making preoperatively.

Intraoperative microscopic photograph showing right C2-ganglion (C2G), lamina and pars of C2 (C2-pars) and spinous process (C2S). The right ganglion is coagulated (A) and cut (B-D) using sharp knife. The articulating surface of C1-lateral mass (F) is seen and one can appreciate the severe joint dislocation in this case. (E, F) The C1–2 joint is opened and the articulating surface of C1 (FC1) and C2 (FC2) seen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study Design

We did a prospective, bicentric study (to exclude surgeon and selection bias), where adult patients (age more than 18 years) of CVJ anomaly were included (operated between the year 2014 to 2019). These patients were operated by senior surgeons of 2 premier institutes of the country (with experience of more than 10 years). Institutional ethical permission and individual consent from patients to use clinical and radiological data for publication were taken at time of admission. All the patients with traumatic, inflammatory, or oncological causes were excluded; patients requiring transoral odontoidectomy were also excluded (as the procedure might interfere with outcome analysis).

2. Study Population

The patients were operated upon either ‘with’ (group A) or ‘without’ (group B) of ganglion preservation. Twelve patients needed C2G-resection (C2Gr) despite of an intent to preserve it and we have highlighted the factors responsible for this ‘change of intraoperative plan’ in the discussion section. Both types of posterior fixation (O-C1L-C2PI and C1L-C2PI) were included in our study and distraction-reduction was done as per the requirement. The selection of patient in 2 groups was merely surgeon’s discretion depending upon the radiology and complexity of CVJ anomaly. As our experience increased, we found certain factors continuously governing the decision-making i.e., our SAVIOUR’s Criteria.

3. Study Parameters

Study parameters included demographical profile, preoperative modified Nurick grade, clinical symptoms, surgical procedure with intraoperative details (blood loss and duration of surgeries), complications, and follow-up [5]. The clinical outcome of C2Gr was assessed by Pain Numeric Rating Scale (0 to 10 scale), Patient Satisfactions Score (5-point scale with best given score of 5 and least given score of 1), and an objective SBSES (Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale) (which comprises 5-point score [width less or more than 2 mm; height with reference to surrounding skin; color; suture marks; and overall appearance]) [6]. The fusion was assessed using Lenke fusion grade and occipital neuralgia or paraesthesia was assessed subjectively on 10-point scale (0–10) [7]. The medical history records and duration for which cervical collar was worn were also noted. These study parameters were compared between the 2 groups of patients (with or without C2G preservation). The joint manipulation is defined as ‘exposure of the joint in full surface area with decortication and accommodating the bone chips or spacer inside’ [2,3].

4. Surgical Technique

All the surgeries were performed under general anaesthesia, in prone position, with neck fixed in extended position and traction (according to weight of patient) applied. We followed standard free-hand technique of knock-and-drill [8]. The incision was standardized starting 1 cm below inion to C3 spinous process and technique of fascia-muscle opening and closing was kept similar among all the patients. After skin incision, the fascia was split in ‘Y’ shaped manner (so as to have advantage in closure), muscles were split (rather than cauterized) using sharp knife and bipolar cautery. The subperiosteum dissection and further steps were performed under microscope. The C2G is skeletonized, dissected, and mobilized to create a window for instrument or joint manipulation (Fig. 2). For rod-and-screw fixation, we follow entry point or trajectory as described by Goel and Harm’s, using high-speed microdrill (Fig. 3) [1-3].

Intraoperative photograph showing steps of C2-ganglion (C2G) preservation posterior fixation. (A, B) The ganglion is dissected and retracted downwards creating a window between C1-posterior arch and ganglion. The C1–2 joint is seen with the articulating surface of C1 (FC1) and C2 (FC2) visible clearly. (C, D) The joint is opened and spacer is inserted.

Intraoperative photograph showing steps of pars of C2 (C2-pars) and C1 lateral mass screw insertion in a case with C2-ganglion (C2G) preservation. (A) After the C2G is dissected, the C1–2 joint is appreciated just below the ganglion. A window is created and after placing the spacer (B), C1-lateral mass in negotiated (C). (D) Then C2-pars screw is inserted. FC1, surface of C1; FC2, surface of C2.

5. Follow-up

The patients were assessed postoperatively at 3, 6, 12 months, and at the last available outpatient visit (at time of writing the paper) and a repeat computed tomography (CT)-scan at 12th month for fusion grade. Patients with follow-up of less than 12 months were excluded from our study. The follow-up was done on outpatient clinic basis (blinded assessment).

6. Statistical Analysis

The IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The confounding effect of age and sex distribution was compared using Fisher exact test. Independent Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare the median distribution of study parameters among the cases and controls. Paired t-tests were used to assess differences between pre- and postoperative outcomes. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

From 2014 to 2019, 414 patients (age, 18–70 years) of CVJ anomaly underwent posterior fusion (O-C1L-C2PI or C1L-C2PI) in 2 institutes. Thirty-four patients were excluded because joint manipulation was not done in them (our initial 20 patients, when we were adapting with Prof. Goel’s technique of joint manipulation; and 9 patients had an abnormal medial course of vertebral artery; 5 patients had C1–2 joint fusion and underwent O-C2PIC3 fixation in situ). One hundred nine pediatric patients were excluded as the functional or neurological assessment and surgical nuances are considered different in this population. So, finally, 171 patients were analyzed in our study (88 patients were included in group A where C2G was preserved [C2Gp], while 83 patients were included in group B, were C2G was sacrificed [C2Gr]). Twelve patients were initially planned for C2G preservation but then C2G could not be preserved intraoperatively so were shifted to group B.

1. Demographical Profile and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 171 patients were analyzed with mean age 46.3 ± 11.2 years (male:female, 76:95); of whom 88 patients (mean age, 48.1 ± 7.7 years; male:female, 40:48) belong to group A (C2Gp) and 83 patients (mean age, 42.6 ± 5.8 years; male:female, 36:47) belong to group B (C2Gr). The median distribution of age between the 2 groups was similar (p > 0.05). The most common clinical symptom was difficulty in walking (spastic quadriparesis, n = 165, 96.5%), followed by neck tilt and pain (n = 17, 9.9%). Thirteen patients (7.6%) had suboccipital numbness and 12 patients (7.0%) had paraesthesia in C2 distribution preoperatively. The median modified Nurick grade was 3.3 (C2Gp, 3.67; C2Gr, 3.3). Radiologically, reducible atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD) was present in 46 patients (26.9%) and irreducible AAD in 125 patients (73.1%). Basilar invagination was seen in 74 patients (43.2%), but only 4 of them, with severe BI, were symptomatic; these 4 needed tracheostomy postoperatively. Other radiological features include occipitalised atlas (n = 68, 39.7%), psuedo facets (n = 17, 9.9%), and torticollis (n = 34, 19.9%).

2. Intraoperative Details and Surgical Outcome

C1L to C2PI fixation was done in 107 patients (62.6%), Occipital plate (O) to C2PI fixation in 54 (31.6%), and suboccipital plate (O) to pedicle of C2 in 10 (5.8%). Mean blood loss in our study was 508 ± 101.3 mL (range, 220 to 1,200 mL) (490 ± 96.2 mL in group A and 525 ± 45.7 mL in group B). The median operative duration was 217.9 and 162.2 minutes in the groups A and B, respectively (p < 0.05). At the follow-up (median, 46.8; range, 12–58 months) Lenke fusion grade A was achieved in 158 patients (92.4%) and grade B was achieved in 13 patients (7.6%). Spacers were appropriately positioned in all patients on postoperative imaging and none of the patients had evidence of instrumentation failure. Postoperative neck pain resolved or improved in all patients. There were 4 instances of vertebral artery injury and 16 patients (9.4%) had cerebrospinal fluid leak. Eighteen patients (10.5%) had postoperative neurological deficit and respiratory distress and required long-term intensive care unit (ICU) admission and tracheostomy (C2Gr, n = 8; C2Gp, n = 10).

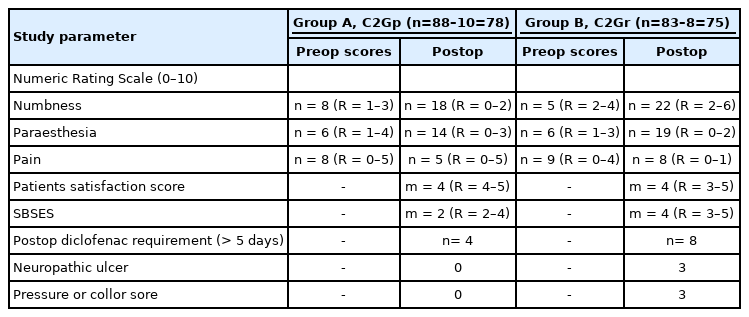

3. Functional Outcome Between the 2 Groups

Excluding the 18 patients who required long-term ICU and tracheostomy, 153 patients (78 in group A and 75 in group B) were assessed for functional outcome. Postoperatively Baclofen 10 mg twice daily for 3 weeks and diclofenac 100 mg twice daily for 5 days were prescribed to all patients. Cervical collar was advised for 3-week postsurgery. A clinical trend suggesting better functional outcomes (numbness, parestheisa, scar outcome, and postoperative ulcer formation) in group A was seen (Table 1). It is interesting to note that all 6 patients who developed ulcer or pressure sore, underwent O-C2PI fixation.

DISCUSSION

The C-ganglion preservation was first described by Goel and Laheri [9] in 1994, among 2 of their patients (out of 30 operated). None of the patient in their series complained of numbness or pain after sectioning the root. The technique described then, was under direct vision, highlighting the use of ‘radius-ulna’ internal fixation stainless-steel plate and screws. The technique was revisited and further discredited in terms that “this seemingly “small” or “minor” surgical step of C2-resection revolutionized the surgical treatment for atlantoaxial stabilization” [10]. C2G resection provides a panoramic view of joints and safe access for the screws with mild inconsequential suboccipital numbness [10]. However, a technique of ganglion preservation was also described in the same article by displacing the C2G inferiorly [10]. Herein lies the ‘intension’ of preserving the ganglion and we strongly believe that the surgeon should ‘always’ try to save C2G.

In our study, 17 patients in group B, experienced new-onset numbness (in C2-distribution) and 13 patients had new-onset paraesthesia; compared to 10 patients having numbness and 8 patients complaining paraesthesia in group A. Contrarily, Kang et al. [11] found that a majority of his patients (19 out of 20) remain unaffected after ganglion resection. Dr. Kang is a tenacious proponent of C2G resection and proposed that the technique allows a better preparation and decortication of the atlantoaxial joint, improves visualization for screw placement, and decreases blood loss and operative time without any major complication. The study population in Kang’s study was less in number (n = 20), in that too, majority (65%) were type II odontoid fracture (which comprises of comparatively easier subset of CVJ anomaly patients) [11]. The prevalence of pressure sore was highest among the patients where occipital plating was done without C2G preservation. One of our patients required the pedicle skin graft for pressure sore. Wherever needed, we followed the technique of resection of Kang et al. i.e., for “distal-type” ganglia the nerve was incised just proximal to the ganglion itself; and for the “proximal-type” ganglia, the ganglion itself was incised [11].

We also found that the patients in group B had more intraoperative blood loss, signifying that resection of ganglion additionally risks vertebral artery injury. The C2G resection is technically challenging owing to profuse bleeding encountered due to large venous channels [12]. Similar observations have been reported by other series showing a trend toward shorter operative times and less blood loss with C2 nerve sacrifice [13-15]. However, all the series used a subjective questionnaire with a small number of patients.

Patients with severe basilar invagination or complex CVJ anomalies may require ganglion resection. Twelve patients in our series needed resection even when we had planned for ganglion preservation preoperatively. However, in the majority of the patients, the window available after mobilization of C2G is sufficient for screw insertion. A theoretical disadvantage of preserving C2G is excessive stretching of the ganglion may lead to cord traction, but this has not been reported yet [16]. In our experience, with a meticulous dissection, we were able to preserve C2G in nearly all the patients we intended to (except 12 patients). The intraoperative time in groups A and B was 217 and 162 minutes, respectively.

Our study is unique, being a prospectively designed, included exclusively CVJ anomaly patients (without traumatic cases), and bicentric design. Another important point, we wish to highlight is that the average distance of the vertebral artery from the ganglion is just 7.5 mm and sometimes its anomalous course further increases complexity. Therefore, extra vigilance is required in the dissection of ganglion around its lateral end [3]. The technique described by Prof. Goel, was modified by Yamagata et al. [4] but experienced substantial intraoperative bleeding from the perivertebral venous plexus. The bleeding was controlled using bipolar coagulation and a fibrin-soaked collagen sponge [15]. In his series of 16 cases, none of the patients had allodynia or neuropathic pain in the C2G distribution, but, the preoperative pain was compared with postoperative dysesthesia without taking into account the medical history (analgesic drug or dosage). In our study, we have tried to eliminate the confounding factor by fixing the dosage schedule of analgesics. In our surgical practise, we never encountered such exsanguinous bleeding till the step when C1–2 joint is open. We believe that a meticulous dissection under high-zoom-in microscope precludes such bleeding.

1. Technical Nuances in C2G Preservation

(1) The C1-entry point is an important factor for the fate of C2G. Patkar [17] described a novel entry point for axis vertebra, which is 3 mm below the midpoint of superior facet and is also the midpoint C1–2 joint. If the surgeon plans Patkar’s entry point, we believe that C2G resection is necessary, otherwise, 2 screws could not be negotiated in the available space. We used 2 entry points in our patients (a) C1-lateral mass (as described by Harm’s), and (b) drilling the posterior arch till lateral mass is reached and then negotiating the lateral mass.

(2) The contour of rod and plate (Goel’s and Harm’s techniques) may be another important determinant. The plates have larger surface area in contact with C2G, and therefore preserving the ganglion may lead to irritation or neuropathic pain. We used bilateral rods (Harm’s modification of Goel’s technique) to affix C1-lateral mass and C2-pars interarticularis. This was marked in another study by Salunke et al. [18]. Among the 3 patients, wherein, he failed to preserve C2G, actually kinking of the nerve root had occurred after tightening the Goel plate [18]. It is interesting to update a fact that in the originally described technique by Harms and Melcher [1], they did not sacrifice the C2G. They used screws with a smooth unthreaded portion to minimize irritation to the ganglion and to facilitate connection to the rod [15]. This is just a theoretical hypothesis and further needs validation.

(3) The C2G occupies nearly 40% (one-third) of the posterior neural foramen area in neutral position, which further increases to 65% (two-thirds) in neck extended position. Therefore, it is advisable to avoid intraoperative hyperextension, if your intension is to preserve C2G [19].

2. Are We Unfair to the Innocent?

The majority of previously published series, discrediting the technique of C2G preservation was of retrospective design and did not consider joint manipulation (Table 2). In a review by Huang et al. [20], some technical issues pertaining to Goel’s procedure and Harm’s procedure were highlighted. The different entry points were the deciding factor for C2G preservation. Prof. Goel used a screw-plate system for atlantoaxial fixation and in order to leave some space for the upper part of the plate, he described a lower screw entry point than what was proposed by Harms and Melcher [1]. As such, cutting the C2G is unavoidable in Goel’s technique, while Aryan’s and Harm’s used screw-rod system wherein, cutting the C2G is avoidable. Huang et al. [21] proposed a ‘screw index,’ as a predictor of C2 nerve dysfunction, which is defined as the ‘difference in height between C2G and its corresponding foramen’; however, this evaluation is not reproducible in all the patients because of failure to distinguish the C2G on CT. In our clinical experience, we believe that majority of cases, with a small C1-lateral mass, can be dealt by drilling posterior arch and subsequently shifting the C1-screw entry point slightly upwards.

Review of the published series (2010–2019) assessing the importance of C2-ganglion preservation or resection in posterior fixation surgery

Janjua et al. [16] proposed that the decision regarding preserving or sacrificing the C2G should be based on the surgical experience and personal preference of surgeon. In another series of 190 cases, Salunke et al. [18] described the various factors determining suitability to preserve the C2G. He showed that the preservation of the C2G is difficult in patients with C1occipital condyle hypoplasia and extremely oblique joints. In our experience, 12 patients needed resection of ganglion, despite our preoperative intent of preservation. These patients had either thick C2G (n = 4), severe basilar invagination (n = 3), venous sinus bleeding (n = 4), and narrow foramen due to hyperextension (n = 1). Salunke et al. [18] used questionnaires and scale to assess the prevalence of sensory loss after C2G-preservation and found that none of his patients experienced C2 nerve-related pain at three and 6 months of follow-up. We did a longer follow-up, with more number of patients (n = 171) and that too from 2 different centers. A similar analysis was done by Hamilton et al. [15], in a series of 44 cases, where he found that patient satisfaction scores were not negatively affected by C2Gr. Eighty percent of their patients had preoperative occipital neuralgia, which got relieved in postoperative course [15]. Therefore, patient satisfaction has to be better because ‘pain’ is the most worrisome symptom. One may interpret this ‘loss of preoperative pain’ as ‘hypoesthesia,’ thereby changing the whole perspective of conclusion. We believe that presence of positive signs like pressure sore, thinning of muscles, dysesthesia, or paraesthesia carry more significance in assessment of C2G preservation. Traynelis [22] supports preservation of C2G and wrote that the key to avoid bleeding from the venous plexus is to limit the dissection to the subperiosteal plane, which may take a few extra minutes. The severing of C2G for wider exposure does not guarantee that a vertebral artery injury will not occur [23,24]. A meta-analysis by Elliott et al. [25] showed that 11.6% of patients with C2G resection experience postoperative C2 numbness compared to 4.7% in whom C2G was preserved. Another comparison was done by Yeom et al. [26] between preservation and resection group, found that outcomes related to occipital neuralgia are better with C2 root preservation than with its sacrifice.

3. SAVIOUR’s Criteria

Over the years and accumulating experience of more than 800 surgeries for CVJ anomaly, we suggest 7 factors that guide a surgeon in deciding whether one should or should not attempt C2G preservation (SAVIOUR’s Criteria). These include Short neck, Anomalous course of vertebral artery, Venous sinus bleeding, Basilar Invagination, Oblique or vertical orientation of C1–2 joint, Using occipital plate i.e., O-C1-C2 fixation, Robust or thick C2G.

In presence of short neck, anomalous vertebral artery course, exsanguinous venous sinus bleeding, radiological evidence of platybasia, severe basilar invagination, and vertical C1–2 joints, one may try to preserve C2G but intraoperative technical difficulties will be more. The subset of patients, wherein, we applied occipital plate, needs special mention. These patients have high likelihood of developing postoperative pressure sore or neuropathic ulcer; as such, one should always try to preserve C2G.

4. Limitation of the Study

The study is single-blinded and the surgeons knew that in which case ganglion preservation is being done, more to it, it was surgeon’s discretion only that in which case he likes to do C2G preservation. Although we included patients from 2 centers, but still a likelihood of selection bias could not be ruled out. Secondly, Stony Brooke’s scale is used for postoperative scars and its use for incision-mark is not yet validated. In the future, if better scales are available, we will like to use that. A randomized study would have been a better choice.

In conclusion, our results support ganglion preservation, especially in the subset of patients where occipital plating is needed. Although our study fails to show any statistical significance, we propose that one should always start with an ‘intent’ of preservation as functional outcome is better. We also recommend the radiological and technical conditions (SAVIOUR) when a surgeon might have to sacrifice C2G.

Notes

The authors have nothing to disclose.