The Rehabilitation-Related Effects on the Fear, Pain, and Disability of Patients With Lumbar Fusion Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The lumbar fusion is an important surgery for the orthopedic diseases. The rehabilitation might improve the outcome of patients with lumbar fusion surgery. The rehabilitation-related effects can be revealed by a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs). The purpose of this study is to clarify the rehabilitation effects in the patients with lumbar fusion surgery.

Methods

We performed a systematic search and a meta-analysis for the RCT of rehabilitation treatment on the patients with lumbar fusion surgery. The comparison between rehabilitation treatment (including psychological rehabilitation, exercise, and multimodal rehabilitation) and typical treatment was performed to find if the rehabilitation treatment can improve the outcome after the lumbar fusion surgery. Fifteen studies of lumbar fusion patients under rehabilitation treatment and typical treatment were enrolled in a variety of rehabilitation modalities. The focused outcome was the rehabilitation-related effects on the fear, disability, and pain of patients after the lumbar fusion surgery.

Results

Five hundred twenty-eight rehabilitation subjects and 498 controls were enrolled. The psychological-related rehabilitation showed a significant decrease in pain-related fear when compared to usual treatment. The multimodal rehabilitation can improve the disability outcome to a greater extent when compared to usual treatment. The multimodal rehabilitation seemed to have a more significantly positive effect to decrease disability after lumbar fusion surgery. In addition, the exercise and multimodal rehabilitation can relieve the pain after lumbar fusion surgery. The exercise rehabilitation seemed to have a more significantly positive effect to relieve pain after lumbar fusion surgery.

Conclusion

The rehabilitation might relieve the pain-related fear, disability, and pain after lumbar fusion surgery.

INTRODUCTION

The lumbar fusion surgery is an important treatment for a variety of orthopedic diseases, including degenerative disc disease, traumatic injury, scoliosis, spondylolisthesis, congenital deformity, spinal tumors, tuberculosis deformity, and pseudoarthrosis, etc [1]. The indications has been broadened in recent years. However, the complications after the lumbar fusion surgery will be the major obstacles for patients to return to normal life and daily function. The complications included the pain-related fear, pain, and disability [2-6], which will be related the outcome. Therefore, the management of the complications after lumbar fusion surgery will be a major issue for the treatment of patients after lumbar fusion surgery.

The rehabilitation might be beneficial for decreasing the pain-related fear, pain, and disability. According to the previous meta-analysis, the complex rehabilitation program might reduce the short-term and long-term disability and fear-avoidance behaviors [7]. However, the low quality evidence might bias the results of the meta-analysis. In addition, another previous systematic review showed no evidence to support the positive effects of rehabilitation in relieving the pain after lumbar fusion surgery [8]. The latest meta-analysis of enrolled more randomized clinical trials (RCTs) studies and showed more conclusive effects of rehabilitation on the pain, fear, and disability [9]. Therefore, more enrollment of RCT studies might be helpful for elucidating the relationship between rehabilitation and relieving effects for the complications after lumbar fusion surgery.

In this study, we will include more RCT studies with the more stringent selection criteria for the enrolled studies. In addition, we will include latest RCT studies of rehabilitation on the patients after lumbar fusion surgery in this meta-analysis. We will also focus on the treatment effects of psychological rehabilitation, which mostly belongs to the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The CBT-related rehabilitation has not been emphasized in previous meta-analysis. Therefore, we chose this kind of rehabilitation as our first measure in this meta-analysis. According to the literature mentioned above, we hypothesized that rehabilitation should have the relieving effects on the pain-related fear, pain, and disability. In addition, different kinds of rehabilitation program might demonstrate the different impacts on the complications after lumbar fusion surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Literature Search and Selection Criteria

The systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews and Interventions. The results were reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [10]. We used the following keywords “rehabilitation” or “lumbar fusion” or “surgery” or “exercise” or “fear” or “pain” or “pain-related” or “disability” or “exercise” or “randomized” or “trials” or “multimodal” or “clinical” or “training” or “short-term” or “function” or “outcome” or “comparison” or “versus” or “usual treatment” or “typical treatment,” and “strength” to search and collect the related articles in the PubMed, ScienceDirect, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus databases, CINAHL (Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and the CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials). The articles were limited to those published or epublished online before March 2022.

The inclusion criteria of enrolled studies were as follows: (1) The comparisons between rehabilitation and usual care or treatment after lumbar fusion surgery. (2) The studies including the baseline and postrehabilitation outcome profile. (3) The studies with detailed data of outcome in the dimension of pain-related fear, pain, and disability. (4) These studies were published in English style in the journals of science citation index database. (5) Experimental rehabilitation or multimodal rehabilitation. The definition of multimodal rehabilitation was simultaneous or sequential application of different rehabilitations with the applications on different dimensions. (6) RCTs. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Detailed outcome data with some parts were unavailable in the content of the articles (the corresponding authors would be inquired about the data we needed in this meta-analysis.) (2) The authors did not respond or already could not have access to the dataset. (3) The studies without the rehabilitation treatment after lumbar fusion surgery. (4) Review articles. (5) Not RCTs. (6) The studies without the comparison between rehabilitation and usual care or treatment after lumbar fusion surgery.

2. Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

The quality of the included RCTs was independently assessed as ‘low,’ ‘uncertain’ or ‘high’ risk of bias by 2 reviewers (CH and LJ), using the Cochrane Collaboration Revised Risk of Bias tool for RCTs (RoB 2.0, version 22 August 2019). Due to the nature of rehabilitation treatment, blinding of participants was impossible. Therefore, the blinding step was not considered in the overall summary risk of bias judgment. The risk of bias for each study was assessed by bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcome, and bias in selection of the reported result. We extracted the following data from the eligible articles. First, the baseline rating scale scores of pain-related fear, pain, and disability of subjects before rehabilitation and routine care respectively. Second, the posttreatment rating scale scores of pain-related fear, pain, and disability of subjects after rehabilitation and routine care respectively. Third, the treatment duration of rehabilitation. Fourth, the baseline and posttreatment rating scale scores of pain-related fear, pain, and disability of subjects under multimodal rehabilitation. For the above data extraction, the sample mean and standard deviation were calculated from reported confidence interval if the standard deviation was not included in the enrolled articles.

3. Meta-Analysis and Statistical Analysis

We used the Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager Software Package (Rev Man Version 5.4) to perform the meta-analyses. The rehabilitation and usual care or treatment were compared to each other to find if the rehabilitation will be superior in decreasing the pain-related fear, pain, and disability. The overall effect size of the baseline and posttreatment rating scale scores of pain-related fear, pain, and disability of subjects was calculated as the weighted average of the inverse variance for the studyspecific estimates. For continuous variables, the weighted mean difference was used to estimate numerical variables. The standardized mean difference was used due to the anticipation of multiple different scales might be used to measure the same outcomes prior to the conduction of current meta-analysis. The method to obtain the standardized mean difference was the Hedges’ (adjusted) g. The χ2 distribution test with Cochran Q, Higgins I2 index, and Tau square test (specific for the random effects model) were used to estimate the heterogeneity. The cutoff value of Higgins I2 index was as follows: 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity*; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity*; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity [11]. The synthesized results were conducted by pooling the data and using a random effects model meta-analysis. In addition, the forest plot was used to estimate if the meta-analysis would favor rehabilitation in decreasing the pain-related fear, pain, and disability when compared to usual treatment.

RESULTS

1. Description of Studies

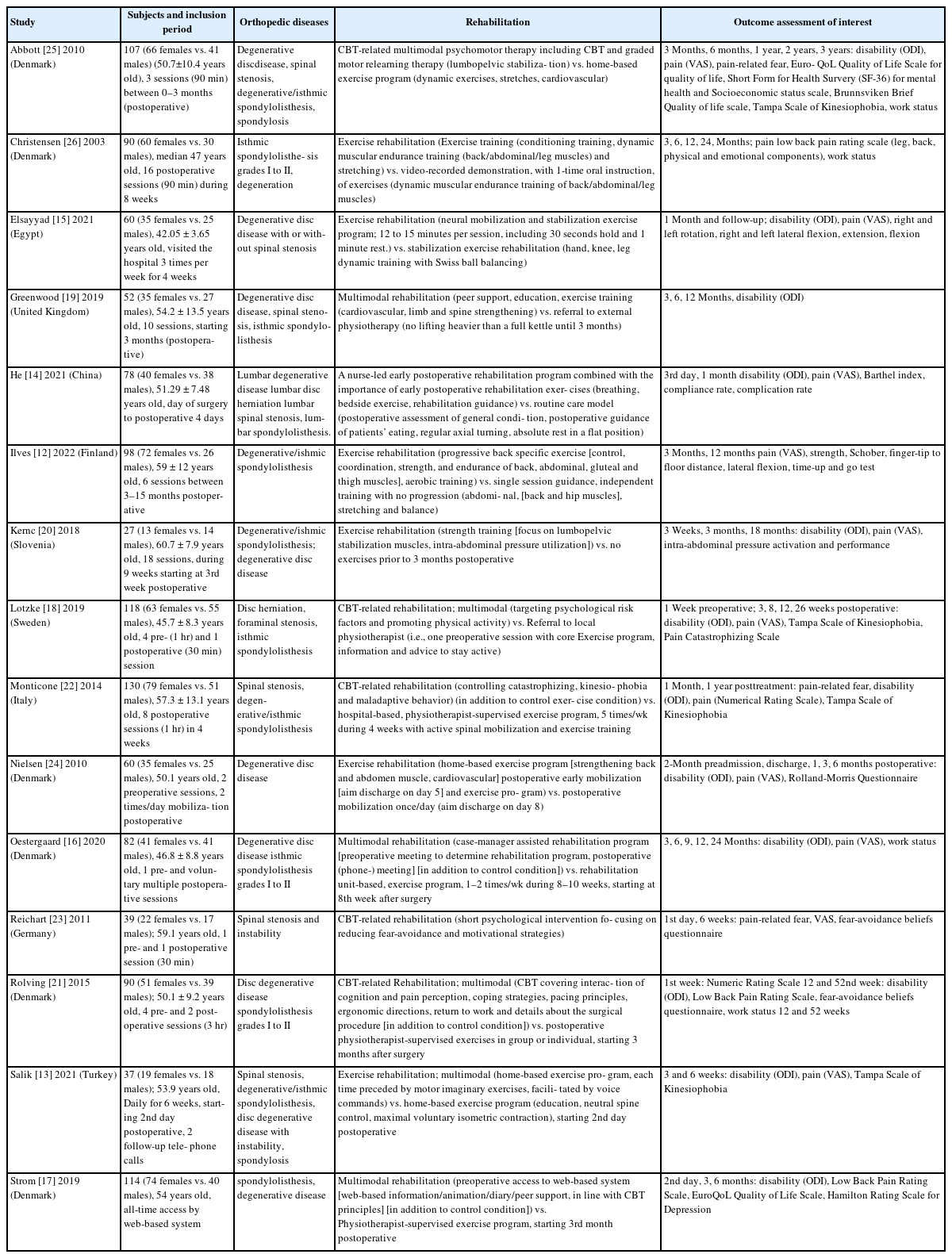

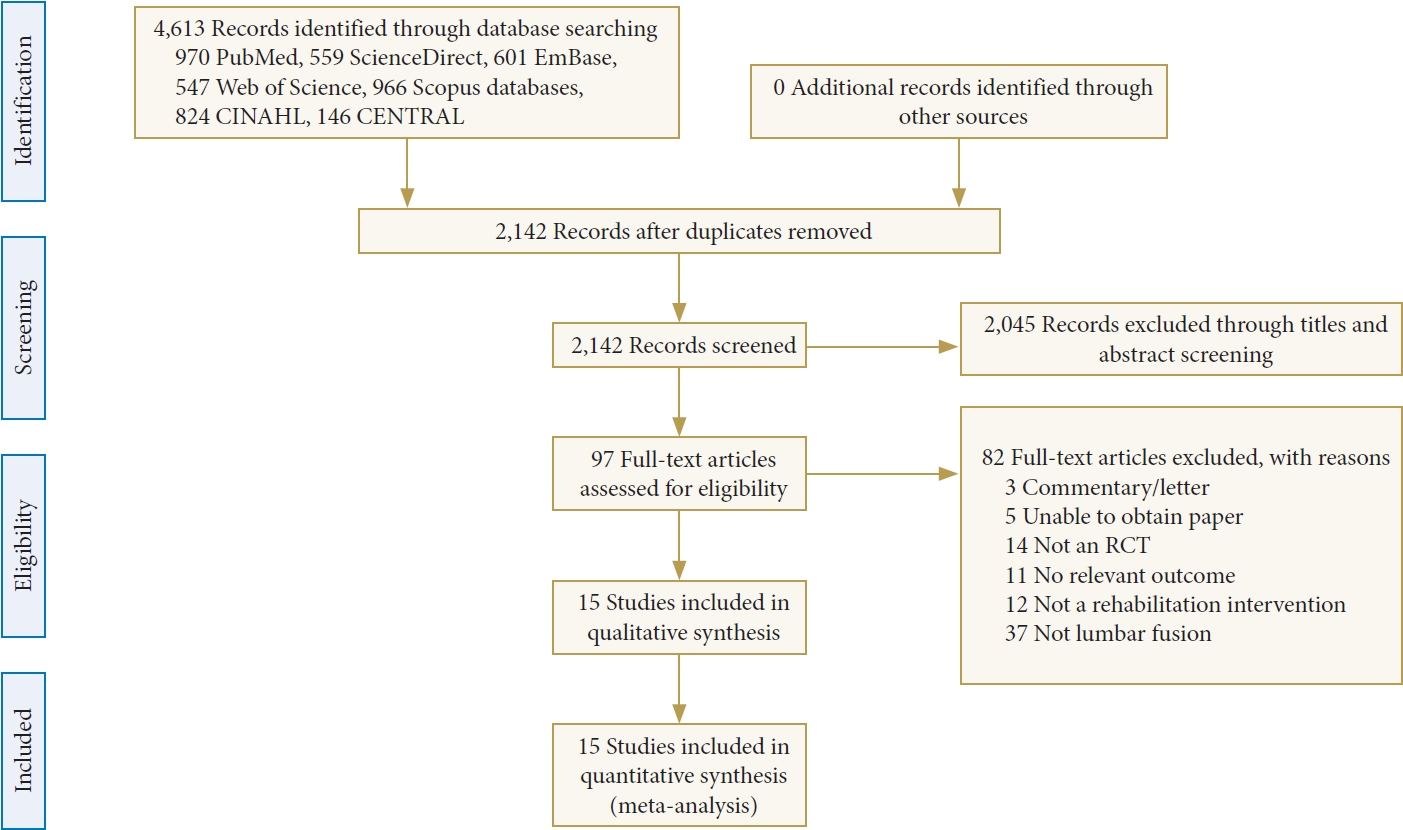

The initial literature search through dataset found 4,613 articles and additional records from other sources were 0 article. Then 2,471 duplicate articles were removed and the residual 2,142 articles were screened according to the relevance of abstracts and titles. The 2,045 articles were discarded after this step. Full text contents were assessed for the eligibility for the 97 articles. Then 82 articles were excluded due to the various reasons (Fig. 1). The qualitative analysis of residual 15 articles was performed and the residual 15 studies were included in this meta-analysis. The flow diagram was presented according to the PRISMA guideline (Fig. 1). The detailed characteristics of the 15 studies [12-26] were also summarized in Table 1. The risk of bias assessment of each study was listed as Fig. 2. The study of Monticone et al. [22] might be the outlier to be excluded in the pain and disability domain due to the high heterogeneity. However, due to that there was no high risk of bias, no huge variation of trial protocol, or no significant difference in trial population, the study was still included in the meta-analysis.

The PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) flow diagram of current meta-analysis. The current meta-analysis followed the PRISMA guideline to identify the potentially relevant literature and screen the identified literature using abstract and title selection. The full text of screened literature was assessed to find the eligible studies and include the suitable ones for the final meta-analysis. RCT, randomized clinical trial.

2. The Meta-Analysis Results for the Pain-Related Fear Under the Comparison Between the Psychological Rehabilitation and Usual Treatment

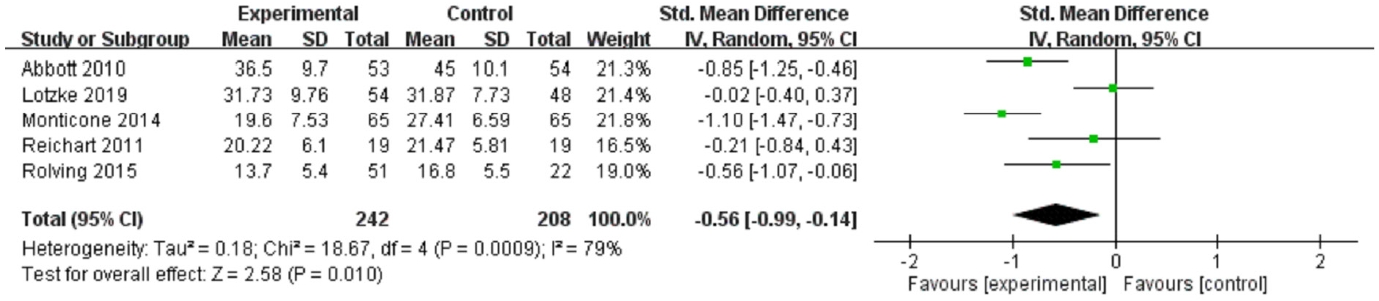

The psychological rehabilitation (CBT-related) group was presented as the “experimental” group in this meta-analysis. The usual treatment group was presented as the “control” group in this meta-analysis (Fig. 3). For the study of Lotzke et al. [18], we collected the data of “Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia” in this meta-analysis. The reason was that we wanted to focus on the kineiophobia, which was more related to rehabilitation perspectives and the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia can objectively quantify the degree of kinesphobia [27]. Total subject number of the psychological rehabilitation (CBT-related) group was 242 and total subject number of the usual treatment group was 208. In the random effect model, the standard mean difference of rating scale scores of pain-related fear between psychological rehabilitation (CBT-related) group and usual treatment group was -0.56 (95% CI, -0.99 to -0.14), which suggested that the rating scale scores of pain-related fear was lower in the psychological rehabilitation (CBT-related) group when compared to usual treatment group. The results were significant (test for overall effect Z=2.58). However, significant heterogeneity was noted (I2=79%).

The forest plot for the meta-analysis results of pain-related fear (psychological rehabilitation [CBT-related] [experimental] vs. usual treatment [control]). The CBT-related rehabilitation were with a lower pain-related fear scores when compared to the usual treatment (statistically significant). A significant heterogeneity was noted. SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom.

3. The Meta-Analysis Results for the Pain Under the Comparison Between the Exercise Rehabilitation and Usual Treatment

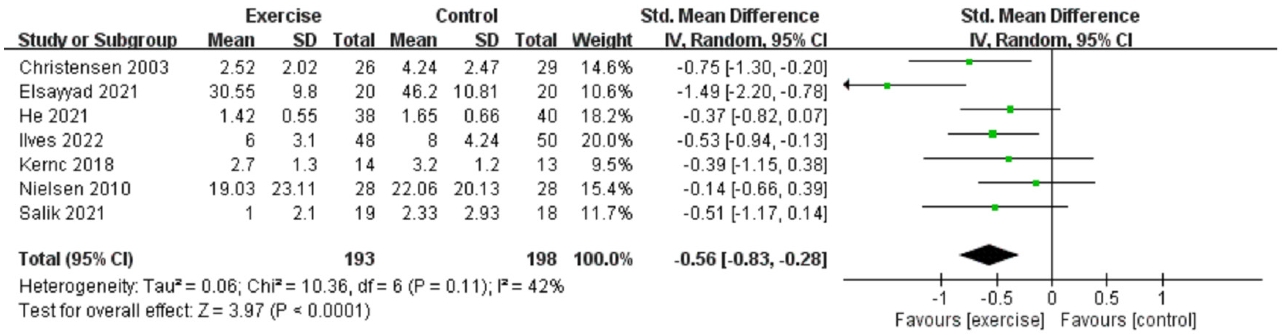

The exercise rehabilitation group was presented as the “exercise” group in this meta-analysis. The usual treatment group was presented as the “control” group in this meta-analysis (Fig. 4). Total subject number of the exercise rehabilitation group was 193 and total subject number of the usual treatment group was 198. In the random effect model, the standard mean difference of rating scale scores of pain between exercise rehabilitation group and usual treatment group was -0.56 (95% CI, -0.83 to -0.28), which suggested that the pain was relatively lower in the exercise rehabilitation group. The results were also significant (test for overall effect Z= 3.97). The significant heterogeneity was also noted (I2= 42%).

The forest plot for the meta-analysis results of pain (exercise rehabilitation [exercise] vs. usual treatment [control]). The exercise rehabilitation was with a lower pain scores when compared to the usual treatment (statistically significant). A significant heterogeneity was noted. SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom.

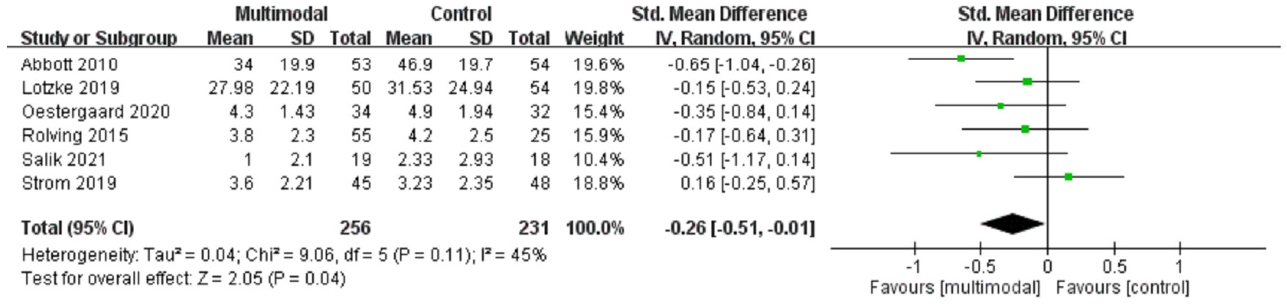

4. The Meta-Analysis Results for the Pain Under the Comparison Between the Multimodal Rehabilitation and Usual Treatment

The multimodal rehabilitation group was presented as the “multimodal” group in this meta-analysis. The usual treatment group was presented as the “control” group in this meta-analysis (Fig. 5). Total subject number of the multimodal rehabilitation group was 256 and total subject number of the usual treatment group was 231. In the random effect model, the standard mean difference of rating scale scores of pain between multimodal rehabilitation group and usual treatment group was -0.26 (95% CI, -0.51 to -0.01), which suggested that the pain was relatively lower in the multimodal rehabilitation group. The results were also significant (test for overall effect Z= 2.05). Moderate heterogeneity was also noted (I2= 45%).

The forest plot for the meta-analysis results of pain (multimodal rehabilitation [multimodal] vs. usual treatment [control]). The multimodal rehabilitation were with a lower pain scores when compared to the usual treatment (statistically borderline significant). A significant heterogeneity was noted. SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom.

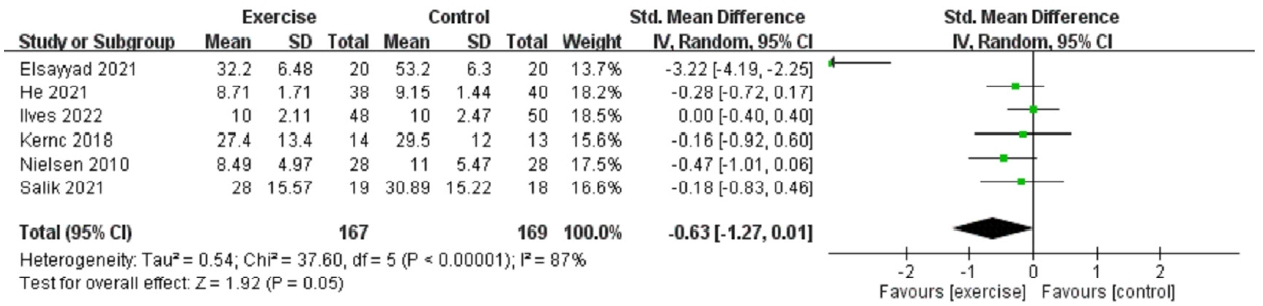

5. The Meta-Analysis Results for the Disability Under the Comparison Between the Exercise Rehabilitation and Usual Treatment

The exercise rehabilitation group was presented as the “exercise” group in this meta-analysis. The usual treatment group was presented as the “control” group in this meta-analysis (Fig. 6). Total subject number of the exercise rehabilitation group was 167 and total subject number of the usual treatment group was 169. In the random effect model, the standard mean difference of rating scale scores of disability between exercise rehabilitation group and usual treatment group was -0.63 (95% CI, -1.27 to 0.01), which suggested that the disability was not significantly lower in the exercise rehabilitation group. The p= 0.05 (test for overall effect Z= 1.92) was statistically significant. However, the 95% CI results still indicated the result was not significant. The significant heterogeneity was also noted (I2= 87%).

The forest plot for the meta-analysis results of disability (exercise rehabilitation [exercise] vs. usual treatment [control]). The exercise rehabilitation were with a lower pain scores when compared to the usual treatment. However, the 95% CI included 0. Therefore, it was not statistically significant. A significant heterogeneity was noted. SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom.

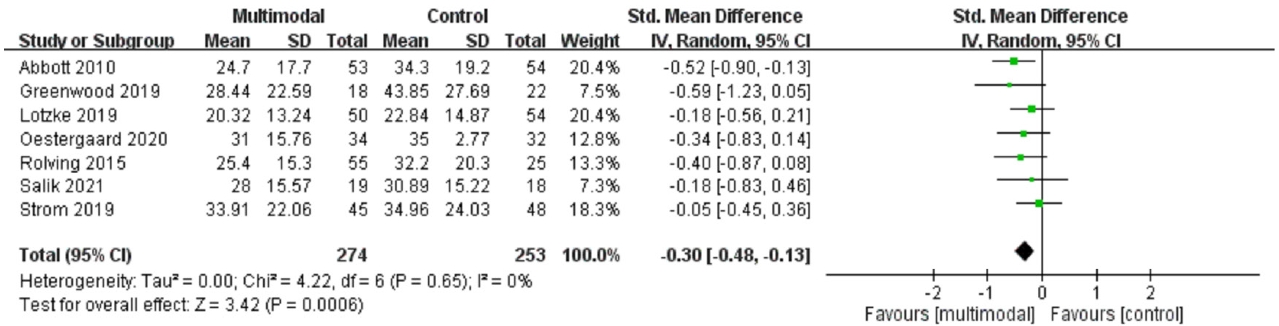

6. The Meta-Analysis Results for the Disability Under the Comparison Between the Multimodal Rehabilitation and Usual Treatment

The multimodal rehabilitation group was presented as the “multimodal” group in this meta-analysis. The usual treatment group was presented as the “control” group in this meta-analysis (Fig. 7). Total subject number of the multimodal rehabilitation group was 274 and total subject number of the usual treatment group was 253. The standardized mean differences between multimodal rehabilitation group and usual treatment group were -0.30 (95% CI, -0.48 to -0.13), which suggested that the disability was relatively lower in the multimodal rehabilitation group. The results were also significant (test for overall effect Z= 3.35). Low heterogeneity was also noted (I2= 0%).

The forest plot for the meta-analysis results of disability (multimodal rehabilitation [multimodal] vs usual treatment [control]). The multimodal rehabilitation was with a lower disability scores when compared to the usual treatment (statistically significant). A significantly low heterogeneity was noted. SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom.

7. Assessments of Certainty (or Confidence) in the Body of Evidence

After our evaluation, we reported the moderate confidence in the effect estimate.

DISCUSSION

Our meta-analysis results found that CBT-related rehabilitation might significantly decrease the pain-related fear when compared to usual treatment. For the disability domain, the multimodal rehabilitation seemed to improve the disability outcome to a greater extent when compared to usual treatment. In addition, the multimodal rehabilitation seemed to have a more significantly positive effect to decrease disability after lumbar fusion surgery. However, the exercise rehabilitation seemed not significantly decrease the disability scores in current meta-analysis. For the pain domain, the exercise and multimodal rehabilitation seemed to decrease the pain after lumbar fusion surgery. The exercise rehabilitation seemed to decrease the pain more than the multimodal rehabilitation on the patients after lumbar fusion surgery. The focus on the CBT-related rehabilitation, exercise, and multimodal rehabilitation with statistically significant results on the pain-related fear, pain, and disability domains was the strength point of our meta-analysis. In addition, the more stringent selection and enrollment of RCT studies in the current meta-analysis might be another strength point. At last, the beneficial effects of the specific type of rehabilitation (CBTrelated rehabilitation for the pain-related fear, multimodal rehabilitation for the disability, and exercise rehabilitation for the pain) can provide the useful information for the clinicians to determine the rehabilitation programs for the patients after lumbar fusion surgery. Our study was different from the latest meta-analysis [9] in several perspectives. First, our search deadline was March 2022, approximately 1 year more than the search deadline of the latest meta-analysis [9]. Second, our meta-analysis enrolled latest references, especially for the articles published in the 2021 and 2022. It might provide a more comprehensive viewpoint. Third, our meta-analysis results showed more significant effects of rehabilitation on the pain-related fear, pain, and disability domains, especially for the effect of the multimodal rehabilitation on the disability domain. Fourth, our meta-analysis focused more on the short-term effects of rehabilitation on the pain-related fear, pain, and disability. Fifth, our meta-analysis enrolled more studies and subjects for the analysis on the pain-related fear, pain, and disability.

Our findings of the positive effects of rehabilitation on pain were opposite of the findings of the previous meta-analysis [8]. The possible reasons might be that the previous meta-analysis enroll too few studies. In addition, our meta-analysis results of CBT-related rehabilitation on the pain-related fear might provide the additional information for another previous meta-analysis [28], which showed that CBT-related rehabilitation did not have a positive effect on the pain and physical function of patients after lumbar fusion surgery. The CBT-related rehabilitation might still has a beneficial effect on the pain-related fear, even without a significant treatment effect on the pain and physical function [28]. The beneficial effect on the pain-related fear might be derived from the improvement of pain coping mechanism [29-31] and reduce the catastrophic fear [21]. The multimodal rehabilitation might be beneficial for decreasing the disability scores, which have been reported in 2 previous meta-analysis studies [7,9]. Our meta-analysis also replicated this finding. It might be related to shift the conceptualization of pain to a coping skill to protect the body tissue [31] during cognitive or educational rehabilitation and interhemispheric interaction to improve the neural plasticity of primary motor cortex during motor rehabilitation [32]. The relief of pain might also be helpful to reduce the disability of patients. The pain-relieving effects of exercise rehabilitation might be due to the enhancement of central descending inhibitory pathway [33] or the modulation of angiotensin or glutamate transmission system [34,35]. However, the exercise rehabilitation seemed not to significantly reduce the disability. The exercise rehabilitation seemed to decrease the pain more than the multimodal rehabilitation on the patients after lumbar fusion surgery. The potential mechanism might be that multimodal rehabilitation focused more on the educational and cognitive training, which might be more focused on decreasing the disability due to the pain-related fear [31] and neural plasticity can improve the disability outcome [32]. The exercise might be more focused on the hypoalgesic mechanism, which involved the central pain inhibition system [33]. It suggested that the different kinds of rehabilitation programs might demonstrate different treatment effects on the outcome of postoperative duration for the patients after lumbar fusion surgery. In the recent study, the rehabilitation might play a role as an independent predictor for the wound complications after lumbar fusion surgery [36]. Even the current metaanalysis did not survey the wound complications, the improvement of disability and pain might be related to the factor. However, a recent study reported that discharged to rehabilitation and discharged to home showed a statistically similar postdischarge morbidity status. The rehabilitation did not predict the postdischarge morbidity [37]. In addition, another meta-analysis of lumbar fusion due to degenerative diseases showed that the evidence of positive effects of rehabilitation on the outcome of patients still have not been significantly proved [38]. Therefore, there is still a lot of space to improve the study design of rehabilitation on the outcome of patients after lumbar fusion surgery. More RCT studies with a better study design can clarify the real effects of rehabilitation on the pain-related fear, pain, and disability of patients after lumbar fusion surgery.

The current meta-analysis did not perform the correlation and cause-relationship analysis between these outcomes. However, the potential relationship pain, pain-related fear, and disability in the patients after lumbar fusion surgery might influence each other. For example, the improvement of disability might be related to the improvement in the pain and pain-related fear. This might be an intrigue issue for further research.

There were several limitations in the current meta-analysis. First, the limited sample size for each comparison (mostly around 100–300 subjects in each group) might limit the interpretation of current results. In addition, most meta-analysis dimensions in the current manuscript just had around 200 subjects for each group. The statistical power from the sample size might be limited in the current meta-analytic results. More subjects will be warranted in the future meta-analysis. Second, a relatively high statistical heterogeneity was noted in the different comparison groups (except the comparison of multimodal rehabilitation for disability). Third, the lack of transparency of detailed rehabilitation programs was noted in the enrolled RCT studies. Fourth, the variability of subject age, sex, and orthopedic diseases in each enrolled RCT study might also bias our findings. Fifth, the variability of treatment duration and enrolled time in each RCT study might be another obstacle to reach a more consistent finding for positive effects of the rehabilitation on the patients after lumbar fusion surgery. Sixth, the statistically significant results might not represent the significant results in the clinical perspective. The most enrolled studies were based on 10-point scale (commonly used in clinical practice). For instance, pooled result of difference in pain scores between exercise and usual treatment may not represent clinically importance due to more than half evidence in the meta-analysis showed mean difference < 2 in original reports. Therefore, the statistically significant results should be interpreted with caution in the viewpoint of clinical perspectives. Seventh, the timing evaluating pain, disability and pain-related fear differs between the enrolled studies was different. For instance, Lotzke et al. [18] initiated the rehabilitation during 8–12 weeks before the surgery but Abbott et al. [25] started it at the first day after the surgery. The timing issue of rehabilitation protocol would also influence the interpretation of current meta-analysis results. Eighth, the diverse contents of CBT-related rehabilitation might influence the pain-related fear outcome. This limitation should be taken into consideration when we interpreted with the current meta-analysis.

CONCLUSION

The rehabilitation might relieve the pain-related fear, disability, and pain after lumbar fusion surgery. The beneficial effects of the specific type of rehabilitation (CBT-related rehabilitation for the pain-related fear, multimodal rehabilitation for the disability, and exercise rehabilitation for the pain) can provide the useful information for the clinicians to determine the rehabilitation programs for the patients after lumbar fusion surgery.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: HC, JL; Data curation: HC, JL; Formal analysis: HC, XH; Funding acquisition: XH; Methodology: HC; Project administration: XH; Visualization: LS; Writing - original draft: HC; Writing - review & editing: XH.