Vertebral Body Sliding Osteotomy as a Surgical Strategy for the Treatment of Cervical Myelopathy: Complications and Pitfalls

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This retrospective cohort study has been aimed at evaluating the incidence of complications after vertebral body sliding osteotomy (VBSO) and analyzing some cases. Furthermore, the complications of VBSO were compared with those of anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF).

Methods

This study included 154 patients who underwent VBSO (n = 109) or ACCF (n = 45) for cervical myelopathy and were followed up for > 2 years. Surgical complications, clinical and radiological outcomes were analyzed.

Results

The most common surgical complications after VBSO were dysphagia (n = 8, 7.3%) and significant subsidence (n = 6, 5.5%). There were 5 cases of C5 palsy (4.6%), followed by dysphonia (n = 4, 3.7%), implant failure (n = 3, 2.8%), pseudoarthrosis (n = 3, 2.8%), dural tears (n = 2, 1.8%), and reoperation (n = 2, 1.8%). C5 palsy and dysphagia did not require additional treatment and spontaneously resolved. The rates of reoperation (VBSO, 1.8%; ACCF, 11.1%; p = 0.02) and subsidence (VBSO, 5.5%; ACCF, 40%; p < 0.01) were significantly lower in VBSO than in ACCF. VBSO restored more C2–7 lordosis (VBSO, 13.9°±7.5°; ACCF, 10.1°±8.0°; p = 0.02) and segmental lordosis (VBSO, 15.7°±7.1°; ACCF, 6.6°±10.2°; p < 0.01) than ACCF. The clinical outcomes did not significantly differ between both groups.

Conclusion

VBSO has advantages over ACCF in terms of low rate of surgical complications related to reoperation and significant subsidence. However, dural tears may still occur despite the lessened need for ossified posterior longitudinal ligament lesion manipulation in VBSO; hence, caution is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Vertebral body sliding osteotomy (VBSO) is a surgical technique for treating cervical myelopathy by anteriorly translating the vertebral body with spondylotic or ossified posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) lesions [1]. It has been known to have several advantages over other anterior cervical decompression techniques, including anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF) or anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) [2,3]. The strengths of VBSO are a faster fusion rate, restoration of cervical lordosis, short operation time, low amount of blood loss, and low risk of dural tears [1-7].

While the advantages of VBSO have been reported by previous studies, not much has been reported regarding the complications and pitfalls of VBSO. Despite the theoretical benefits of this technique, VBSO may not be free from complications. Approach-related complications such as dysphagia and dysphonia cannot be completely avoided with VBSO. Furthermore, VBSO cannot be free from hematoma or dural tears since these complications do occur even in more simple procedures such as ACDF. Furthermore, VBSO is a unique construct that involves the anterior translation of the vertebral body, which poses the possibility of unexpected complications. Along with its advantages, surgeons who are new to this technique should be aware of possible complications and pitfalls to provide favorable and stable outcomes. Moreover, these factors are essential when selecting a surgical method for the treatment of cervical myelopathy.

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the incidence of complications after VBSO, analyze complication cases, and compare the complications after ACCF with those of VBSO, to improve the overall understanding and comprehensively summarize the complications of VBSO; we believe this will improve the confidence of surgeons attempting this novel indirect anterior decompression technique.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study Design and Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the data of all 218 patients who underwent VBSO and ACCF between 2006 and 2020. All of the surgeries were performed by 1 surgeon (DHL). Since 2011, VBSO has been conducted and has been given priority over ACCF in cases of OPLL or spondylotic cervical myelopathy requiring corpectomy. And the study only included patients who underwent VBSO procedures after 2012, considering the learning curve with this procedure. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center (IRB number: 2022-0840). All procedures were carried out in compliance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with cervical myelopathy and followed up for more than 2 years. Cases that required only 1 or 2 levels of vertebral body sliding were included for VBSO, while cases that necessitated sliding for 3 or more levels underwent posterior or combined surgery and were excluded from this study. Furthermore, in cases where there is a local lesion around the endplate rather than a pathological lesion throughout the vertebral body at the cephalad and caudal levels in VBSO, the problem lesion was removed through discectomy and trumpet osteotomy procedure without sliding. In the case of ACCF, only one vertebral body corpectomy was included. Additionally, the following cases were also excluded from the study: (1) prior cervical spine surgery; (2) diagnosis of a tumor, infection, or fracture at the cervical spine; (3) OPLL or spondylotic lesions at a high level of the cervical spine; and (4) simultaneous posterior cervical fusion (Fig. 1).

2. Variables

Data on age, sex, past medical history, smoking status, body mass index, operating time, length of hospital stay, follow-up period, the number of involved levels of surgery, and complications were collected from medical records. Neck pain visual analogue scale (VAS), Neck Disability Index (NDI), and Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) scores for clinical evaluation and C2–7 lordosis, segmental lordosis, C2–7 sagittal vertical axis (SVA), fusion status, and significant subsidence were evaluated for radiological assessment.

Analysis of complications was divided into 2 categories: perioperative and delayed complications. Complications were classified as “perioperative” if they occurred during the first postoperative month and as “delayed” if they occurred after the first postoperative month [8]. Reoperation was independently analyzed as it was performed perioperatively or delayed depending on specifically related complications.

3. Statistical Analysis

Parametric statistical analyses were performed for normally distributed variables and nonparametric statistical analyses for other variables. Comparisons of the continuous variables of each group were performed using independent sample t-tests. For nominal variables, Fisher exact test or chi-square test was performed. The paired t-test was performed to analyze changes in postoperative values compared with preoperative values. Interobserver and intraobserver agreements were assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and kappa coefficient. The kappa coefficients for the intraobserver reliability were 0.926 for fusion status and 0.89 for significant subsidence. The ICC for intraobserver reliability for the measurement of subsidence was 0.871. The ICCs for sagittal alignments were 0.968 (C2–7 lordosis), 0.935 (segmental lordosis), and 0.913 (C2–7 SVA).

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 154 patients followed up for more than 2 years were included in this retrospective study (VBSO, n = 109; ACCF, n = 45). The VBSO group included 73 men and 36 women (mean age, 59.3±9.8 years). There were no significant age and sex differences between the VBSO and ACCF groups. The number of levels involved in the operation was significantly higher in the VBSO group (2.8±0.4) than in the ACCF group (2.0±0.0) (p < 0.01). The operation time and length of hospital stay of the VBSO group were not significantly different from those of the ACCF group (operation time: 210.2±37.6 minutes vs. 203.9±29.6 minutes; p = 0.21; length of hospital stay: 5.7±3.4 days vs. 6.2±3.4 days; p = 0.26). The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Among the surgical complications, the incidence of dysphagia (n = 8, 7.3%) was the highest, followed by a significant subsidence rate (n = 6, 5.5%). A total of 5 cases of C5 palsy (4.6%) occurred after VBSO. In addition, dysphonia (n = 4, 3.7%), implant failure (n = 3, 2.8%), pseudoarthrosis (n = 3, 2.8%), dural tears (n = 2, 1.8%), and reoperation (n = 2, 1.8%) were observed subsequently. There were no cases of neurologic deterioration, graft dislodgement, or infection after VBSO. There was a significant difference between the groups only in the rates of reoperation (VBSO, 1.8%; ACCF, 11.1%; p = 0.02) and significant subsidence (VBSO, 5.5%; ACCF, 40%; p < 0.01). There was no difference in neurologic deterioration (VBSO, 0%; ACCF, 4.4%; p = 0.08), dural tear (VBSO, 1.8%; ACCF, 2.2%; p = 1.00), dysphagia (VBSO, 7.3%; ACCF, 13.3%; p = 0.24), dysphonia (VBSO, 3.7%; ACCF, 4.4%; p = 1.00), C5 palsy (VBSO, 4.6%; ACCF, 0%; p = 0.32), graft dislodgement (VBSO, 0%; ACCF, 4.4%; p = 0.08), infection (VBSO, 0%; ACCF, 2.2%; p = 0.29), implant failure (VBSO, 2.8%; ACCF, 8.9%; p = 0.20), and pseudoarthrosis (VBSO, 2.8%; ACCF, 8.9%; p = 0.20) between the groups (Table 2).

The clinical and radiological outcomes are summarized in Table 3. There were no significant differences between VBSO and ACCF in terms of neck pain VAS, NDI, and JOA scores. The final radiological alignments showed that C2–7 lordosis (p = 0.02) and segmental lordosis (p < 0.01) were more restored in the VBSO group (C2–7 lordosis, 13.9°±7.5°; segmental lordosis, 15.7°±7.1°) than in the ACCF group (C2–7 lordosis, 10.1°±8.0°; segmental lordosis, 6.6°±10.2°).

DISCUSSION

Based on the results of our study, previously unreported complications were noted, including reoperation, C5 palsy, dysphonia, and implant failure. One case of dural tear was reported from this retrospective review in addition to previous reports [3,5]. But when VBSO was compared to ACCF, it was found to be a safe surgical technique with significantly lower reoperation and subsidence rates.

1. Reoperation

Even though few studies have compared reoperation rates after anterior cervical fusion surgery for cervical myelopathy, ACCF is known for having a higher reoperation rate than ACDF [9,10]. And like the ACDF group in the previous study [9], the reoperation rate (n = 2, 1.8%) in the VBSO group was significantly lower than that of ACCF (n = 5, 11.1%; p = 0.02). All cases that needed reoperation were of radiculopathy that originated from adjacent segmental disease (ASD) after VBSO. In the systemic review by Carrier et al. [11], the ASD incidence for 1- or 2-level ACDF was reported to be 5.48%, higher than that of our study, for an average follow-up period of 106.5 months. The incidence of reoperation for ASD after VBSO should be further analyzed, as the follow-up period for VBSO was 44.8 months shorter than in the previous study. Contrary to the VBSO group in which ASD was the main cause of reoperation, hematoma evacuation (n = 2) and graft dislodgment (n = 1) were the main reasons for reoperation surgery in the ACCF group. There were no cases of neurological deterioration, graft dislodgment, or infection after VBSO, compared with ACCF. Therefore, VBSO seems to be a safe surgical technique with no life-related complications.

2. Significant Subsidence

Severe subsidence is correlated with poor clinical outcomes after anterior cervical fusion surgery [12,13]. Moreover, it may cause instability, neurological deterioration, and mechanical failure [14]. Therefore, a lower significant subsidence rate in the VBSO group is a technical advantage of VBSO over ACCF. As the vertebral body was preserved and multiple screw fixations were performed in VBSO, the distribution of load stress was smaller and the lever arm affecting the vertebral body was shorter in the VBSO group, which provided a lower rate of significant subsidence in the VBSO group [3]. Furthermore, as proven in the previous study, VBSO reached a stable construct earlier than in the ACCF group as the intra or extragraft bone bridging appeared faster in VBSO than in ACCF [3]. None of the patients with significant subsidence needed special surgical treatment because they were free of symptoms or they achieved fusion early in VBSO. Compared to the ACCF group, there were no cases of graft dislodging in the VBSO group. This proves that the VBSO group gained stability faster.

3. Dural Tears

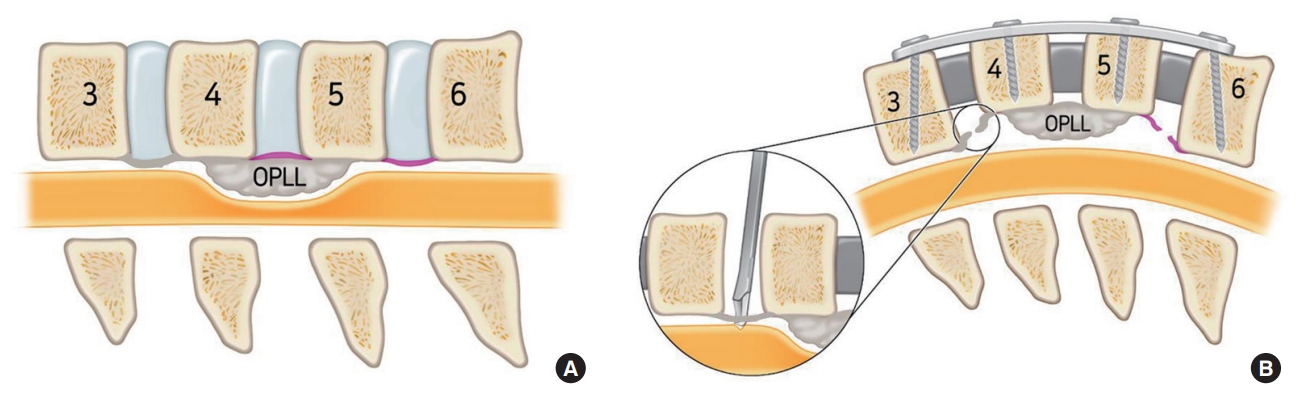

A surgical advantage of VBSO is the lack of the need to directly remove spondylotic or OPLL lesions [1]. Therefore, contrary to ACCF, which directly manipulates and removes compressive lesions, VBSO is much more free from extensive dural defects [5]. And only one case of dural tear after VBSO has been reported [3,5]. However, from the retrospective review of all surgical complications, 2 cases of dural tears occurred during the resection of the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) (Fig. 2) and the accompanying unco-foraminotomy. For the anterior translation of the affected vertebral body with pathologic lesions, PLL resection should be performed behind the uppermost and lowermost discs (Fig. 3). During this procedure, a dural tear occurred, and a dural patch was used to seal the torn site. Another case of dural tear occurred during unco-foraminotomy, a routine procedure. Although VBSO was designed to decrease the complication rate of corpectomy, dural tears can still occur; hence, special care is needed when resecting the ligament around an OPLL mass or when performing accompanying procedures. Furthermore, patients with the wide-base type or continuous type of OPLL are not good candidates for VBSO [1]. As these types make it difficult to resect PLL and anteriorly translate the vertebral body, dural tears could occur during the procedure. For these patients, other techniques such as posterior decompression surgery or ACCF would be recommended. However, despite the higher proportion of OPLL in the VBSO patient group, there was no significant difference in the proportion of dural tear between the VBSO and ACCF groups. This is considered a clear advantage of VBSO not directly manipulating OPLL.

Representative case of dural tear during vertebral body sliding osteotomy. (A–C) A preoperative radiograph and computed tomography (CT) images. (D, E) Postoperative images with anteriorly translated C4 and C5. (F) CT images after posterior longitudinal ligament resection at C5-6-disc space. During resection, a dural tear occurred.

PLL resection procedure in vertebral body sliding osteotomy. (A) OPLL compressing the spinal cord. Pink section indicates PLL. (B) For the translating affected vertebral body, PLL cutting was required. However, as seen in the circle, the dural tear could occur during PLL resection. OPLL, ossified posterior longitudinal ligament; PLL, posterior longitudinal ligament.

4. C5 Palsy

In the previous study by Lee et al. [2], more lordosis could be gained after VBSO than after ACCF. However, the rapid increase in cervical lordosis is known as a risk factor for C5 palsy after anterior cervical fusion surgery [15]. Even though there was no significant difference in C5 palsy rates between the 2 groups, the number of C5 palsy cases was not ignorable in the VBSO group (n = 5, 4.6%). While there was no case of C5 palsy in the ACCF group, it was reported as the second most common perioperative surgical complication following dysphagia in the VBSO group. The VBSO level of the patients with C5 palsy included all of C5 vertebra. However, all C5 palsy patients recovered spontaneously within 1 year of follow-up (Table 4). In the cases of severe C5 palsy, the motor grade decreased from grade 4+ to grade 2. However, all patients recovered to a minimum motor grade of 4 or higher. Therefore, close observation with reassurance during the follow-up period is essential as the patients recover from C5 palsy. However, since the number of patients with C5 palsy is still small, further studies may be needed to analyze this issue.

5. Dysphagia

Dysphagia frequently occurs following anterior approach-related cervical surgeries, including ACDF and ACCF [16-18]. In the previous study, dysphagia was the most common complication following ACDF, observed in 9.5% of patients [16]. The rate of dysphagia in our study was 7.3% in VBSO and 13.3% in ACCF. Dysphagia was the most frequent VBSO-related complication in this study. However, all cases were mild dysphagia that did not need special treatment. Even though the vertebral body is anteriorly translated in the VBSO procedure, the protruded body is removed for anterior plating. Therefore, it is considered that the incidence of dysphagia was not particularly high compared to ACCF.

6. Other Complications

Implant failures, including screw breakage (n = 1) and pull-out (n = 2), were observed during the follow-up period in the VBSO group. However, none of the cases needed revision surgery (Fig. 4). The acquisition of stabilization with an earlier fusion rate would minimize the possibility of reoperation surgery from implant failure. In addition, dysphonia and pseudoarthrosis were observed in the VBSO group, but the rate of complications was not significantly different from that in the ACCF group. In the case of pseudoarthrosis in VBSO, additional surgical treatment was not performed because there were no related symptoms. Dysphonia could occur during anterior approach-based cervical surgeries, especially when the recurrent laryngeal nerve was damaged [19-22]. During the approach, special care would be needed to prevent this complication by avoiding cauterization, retraction, or pressurization [19].

Representative case of implant failure after C4–5 vertebral body sliding osteotomy. Preoperative (A) and postoperative day 2 (B) radiographs without implant failure. (C) Pull-out of the inserted screw was first observed at 1-month postoperative follow-up. (D) Final. The pulled-out screw did not show any change with a solid fusion state.

This study has some limitations. First, VBSO has been preferentially performed rather than ACCF in cervical myelopathy patients since 2012, which has made the number of patients in the VBSO and ACCF groups inevitably disparate. However, the number of VBSO patients, which was only 20–40 in previous studies, increased significantly up to 109 patients in the current study, and they showed a higher variety of complications than those in previous studies [3-5]. Second, the follow-up periods of VBSO and ACDF were significantly different, which possibly affected the delayed complication rates. However, most of the delayed complications, including graft dislodgment, subsidence, implant failure, and pseudoarthrosis, were associated with instability after surgery. Considering that the fusion rates at a minimum of 2 years after surgery were not significantly different between the groups [3], we believe that there would not be much difference in the complication rates with a longer follow-up period in the VBSO group. Finally, the study is not free from potential bias due to the retrospective study design. In the future, a prospective study comparing VBSO and ACCF based on the same pathology will be necessary.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, all surgical complications related to VBSO were reviewed and compared with those related to ACCF, and it showed that VBSO has obvious advantages over ACCF in terms of the low rate of surgical complications related to reoperation and significant subsidence. However, dural tears may still occur despite the lesser need for OPLL lesion manipulation in VBSO; thus, caution is warranted. As C5 palsy and mild dysphagia could occur after VBSO, patients need to be followed up and reassured that most cases spontaneously recover.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: DHL, STC, SP; Formal Analysis: STC, SP, CJH. Investigation: STC, SP, JHK; Methodology: DHL, STC, SP, CJH, JHC; Project Administration: DHL, STC, SP, CJH, JHC, JHK; Writing – Original Draft: STC, SP; Writing – Review & Editing: DHL, STC, SP, CJH, JHC, JHK.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this work was presented in abstract form at the Cervical Spine Research Society (CSRS) 50th Annual meeting, in San Diego, California, on November 18, 2022.