Is Direct Decompression Necessary for Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion (LLIF)? A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Direct and Indirect Decompression With LLIF in Selected Patients

Article information

Abstract

Objective

To compare the clinical and radiographic outcomes following lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) between direct and indirect decompression in the treatment of patients with degenerative lumbar diseases.

Methods

Patients who underwent single-level LLIF were randomized into 2 groups: direct decompression (group D) and indirect decompression (group I). Clinical outcomes including the Oswestry Disability index and visual analogue scale of back and leg pain were collected. Radiographic outcomes including cross-sectional area (CSA) of thecal sac, disc height, foraminal height, foraminal area, fusion rate, segmental, and lumbar lordosis were measured.

Results

Twenty-eight patients who met the inclusion criteria were eligible for the analysis, with a distribution of 14 subjects in each group. The average age was 66.1 years. Postoperatively, significant improvements were observed in all clinical parameters. However, these improvements did not show significant difference between both groups at all follow-up periods. All radiographic outcomes were not different between both groups, except for the increase in CSA which was significantly greater in group D (77.73 ± 20.26 mm2 vs. 54.32 ± 35.70 mm2, p = 0.042). Group I demonstrated significantly lower blood loss (68.13 ± 32.06 mL vs. 210.00 ± 110.05 mL, p < 0.005), as well as shorter operative time (136.35 ± 28.07 minutes vs. 182.18 ± 42.67 minutes, p = 0.002). Overall complication rate was not different.

Conclusion

Indirect decompression through LLIF results in comparable clinical improvement to LLIF with additional direct decompression over 1-year follow-up period. These findings suggest that, for an appropriate candidate, direct decompression in LLIF might not be necessary since the ligamentotaxis effect achieved through indirect decompression appears sufficient to relieve symptoms while diminishing blood loss and operative time.

INTRODUCTION

Lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) stands as an effective method for treating patients with degenerative lumbar disease. It has been proven to provide significant improvement of both clinical and radiological outcomes [1-4]. LLIF employs an indirect decompression technique, which helps alleviate nerve root compression without the need for laminectomy. Indirect decompression effect through LLIF is accomplished by several mechanisms, including restoration of disc and foraminal height (FH), relieving pressure on the neural elements by unbuckling the ligamentum flavum, and addressing sagittal and coronal deformities to achieve proper spinal alignment. Indirect decompression effect after LLIF has been shown to successfully improve pain and disability from degenerative lumbar disease [5,6]. Moreover, this procedure can be performed using minimally invasive approach, resulting in reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery compared to traditional open surgery [7,8].

Although LLIF with indirect decompression surgery is generally effective, there have been reported cases where reoperations were necessary due to insufficient neural decompression from indirect mechanism [9]. In certain instances, LLIF with indirect decompression did not provide the satisfactory clinical improvement, and patients required subsequent reoperation for additional posterior direct decompression [10-12]. While the posterior decompression procedure provides direct decompression and clear visualization of the neural structures, it causes damage to paraspinal musculature as well as disruption of the posterior tension band structures [13].

Several studies have investigated the factors that could aid in identifying appropriate candidates for indirect decompression with LLIF, as well as the risk factors associated with potential failure. Recently, we have proposed the patient selection criteria for indirect decompression with LLIF, including significant pain relief when resting in a supine position, increased disc height (DH) when changing from upright to supine positions, absence of profound weakness, and absence of facet cyst or bony lateral recess, which demonstrated a satisfactory success rate surpassing 90% [10]. Despite number of studies, there is ongoing debate and lack of consensus concerning the necessity of direct decompression in LLIF procedures [14,15]. Furthermore, as of now, there are no randomized controlled trials that directly compare outcomes between LLIF with indirect decompression alone and LLIF with additional direct decompression.

The aim of this study is to address whether additional direct decompression is necessary after LLIF or if indirect decompression alone is sufficient when patients meet all of aforementioned prerequisite criteria. Consequently, we conducted a prospective, randomized controlled study for a comparative analysis of clinical and radiographic outcomes, complications, and the requirement for reoperations following LLIF with and without additional direct decompression in selected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study Design

This study used 2 parallel groups with a 1:1 allocation ratio to compare the outcomes of LLIF with indirect decompression alone and LLIF with additional direct decompression for patients with lumbar degenerative diseases in King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital (Bangkok, Thailand) from April 2021 to April 2022. We obtained an approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (IRB No. 083/64). The study was registered with Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR ID: TCTR20191229003). All patients included in the study received treatment from a single senior spine surgeon with high expertise in LLIF surgery.

2. Participants

Upon obtaining informed consent, potential participants meeting the following criteria were considered for enrollment in the study: patients aged ≥ 18 years who had been diagnosed with degenerative lumbar diseases including single-level lumbar stenosis, spondylolisthesis, or herniated nucleus pulposus at the levels of L2–5 with persistent symptoms for a minimum of 3 months despite conservative treatments. Furthermore, participants needed to fulfill all the prerequisites for indirect decompression procedure, as outlined in our previously published study [10], which included (1) presence of dynamic clinical symptoms (having pain relief when resting in a supine position), (2) presence of reducible DH (having at least 1-mm discrepancy in DH between supine and upright positions), (3) absence of profound weakness (having motor strength of lower extremities > grade III), and (4) absence of static stenosis such as facet cyst or bony lateral recess.

Patients who met any of the following criteria were excluded from the study: those with untreated osteoporosis, cauda equina syndrome, spinal tumors, infectious pathologies, fractures, prior lumbar spinal surgery, anatomical factors that made LLIF unfavorable (such as lack of a suitable corridor or previous retroperitoneal surgery), or those who were unable to complete the follow-up program.

Baseline demographic data including age, gender, preoperative diagnosis, level of surgery, comorbidity, preoperative clinical and radiographic data were recorded.

3. Interventions

The navigated-assisted LLIF was performed by the experienced spine surgeon (WL). Patients were placed under general anesthesia in a right lateral decubitus position. The target disc level for LLIF was confirmed under guidance from an intraoperative computed tomography (CT) navigation (StealthStation, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). With the assistance of the navigation, a mini-open incision was made to access the retroperitoneal space. Blunt dissection and sequential soft tissue dilation were performed to identify the intervertebral disc through a pre-psoas approach. Discectomy and endplate preparation were carried out meticulously to avoid iatrogenic endplate injury. A trial of implant was done, followed by the placement of an LLIF cage (OLIF25 Clydesdale Spinal System, Medtronic), packed with recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) (Infuse, Medtronic) was implanted. Intraoperative CT scan was conducted to confirm appropriate cage positioning, after which the lateral incision was sutured. Subsequently, the patient was repositioned in the prone position for percutaneous pedicle screw and rod placement (Fig. 1). In cases where LLIF with direct decompression was planned, microscopic-assisted unilateral laminotomy for bilateral decompression was performed (Fig. 2). All patients followed the same postoperative rehabilitation protocol and received similar pain medication. Follow-up visits were scheduled at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery for clinical and radiologic assessments. Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT scans were scheduled at 3 and 12 months postoperatively to assess the decompression status, cage subsidence, and fusion rate.

(A) Preoperative midsagittal (left) and axial (right) T2-weighted images, and (B) postoperative midsagittal (left) and axial (right) T2-weighted images of a patient who underwent L3–4 lateral lumbar interbody fusion with indirect decompression (group I).

4. Outcomes

1) Patient-reported outcomes

Clinical outcomes including the visual analogue scale of back (VAS-B) and leg pain (VAS-L), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), and complications were assessed by the research assistant using questionnaire before the surgery and every postoperative follow-up visit [16]. Any patient who failed to achieve more than 50% improvement in either back or leg pain would be classified as indirect decompression failure and subsequently underwent a revision surgery with posterior direct decompression.

2) Radiographic outcomes

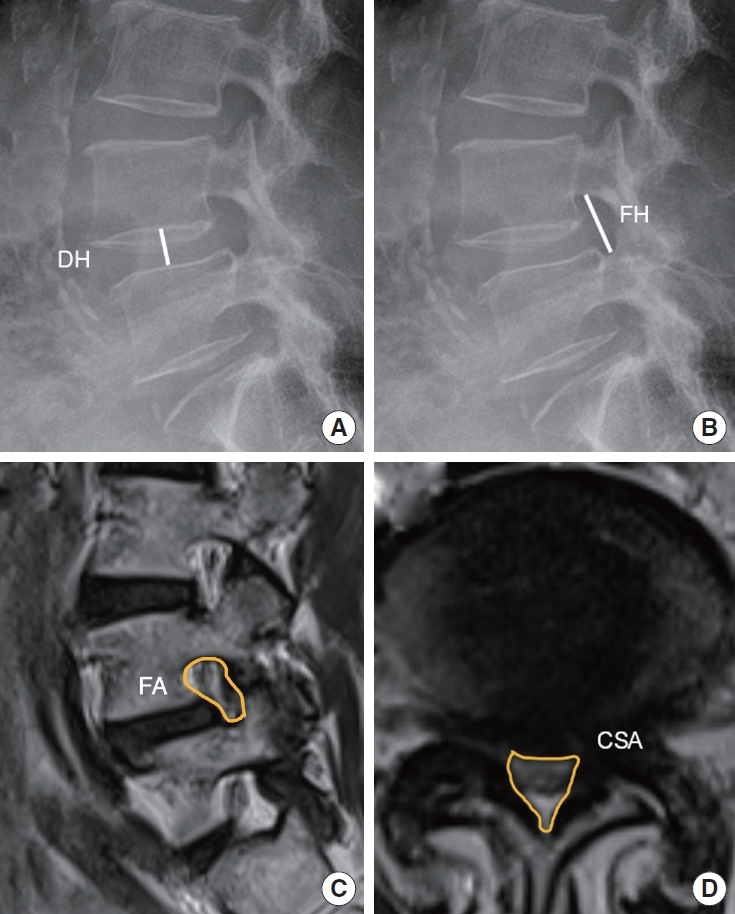

Every included patient had postoperative plain radiographs, CT and MRI for radiographic measurement. Cross-sectional area (CSA) of the thecal sac, DH, FH, and foraminal area (FA) were measured. DH was defined as the distance between the upper endplate of lower vertebra and the lower endplate of upper vertebra measured at middle position of the endplate. FH was defined as the longest distance between the upper vertebra pedicle and the lower vertebra pedicle. T2-weighted MRI was used to evaluate the FA and CSA (Fig. 3). Segmental lordosis (SL) was defined as an angle between the superior margin of upper instrumented vertebral body and the inferior margin of lower instrumented vertebral body. Lumbar lordosis (LL) was defined as an angle between the superior endplate of L1 vertebral body and the superior endplate of S1 vertebral body. The assessment of fusion status was conducted using CT scans and evaluated using the modified Bridwell fusion grading system with consideration of the presence of bone remodeling, bridging bone between the implant and vertebral endplates, and lucency around the graft. The radiologist who did not involve in this study did the radiographic measurement.

5. Sample Size Estimation

For the power analysis, the significance level was set at alpha=0.05 with a power of 90%. The calculation of the sample size was carried out using the formula for independent samples with continuous endpoint with the data drew upon information from a study by Mun et al. [17] providing the pooled variance of direct and indirect decompression groups, along with the minimal clinically important difference of VAS-B, VAS-L, and ODI from a study conducted by Copay et al. [18]. Using these assumptions, with 20% dropout rate, we ascertained that a collective sample size of 24 participants, evenly distributed with 12 in each group, would adequately meet the requirements of this study to detect difference between groups.

6. Randomization and Blinding

Prior to the surgery, a computer-generated randomization procedure was executed by a research assistant. This involved utilizing a block-of-four randomization approach with an equal allocation ratio of 1:1. This process was responsible for assigning patients into either LLIF with indirect decompression (group I) or LLIF with direct decompression (group D) arms. To ensure objectivity throughout the study, both the patients and the evaluator responsible for assessing clinical outcomes were kept unaware of the assigned treatment, maintaining a blinded approach.

7. Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Participant characteristics are presented as mean± standard deviation for continuous variables or frequency (percent) for categorical variables. Within each group, a comparison between baseline and the 1-year follow-up was conducted, and between-group comparisons were made using the Student t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05.

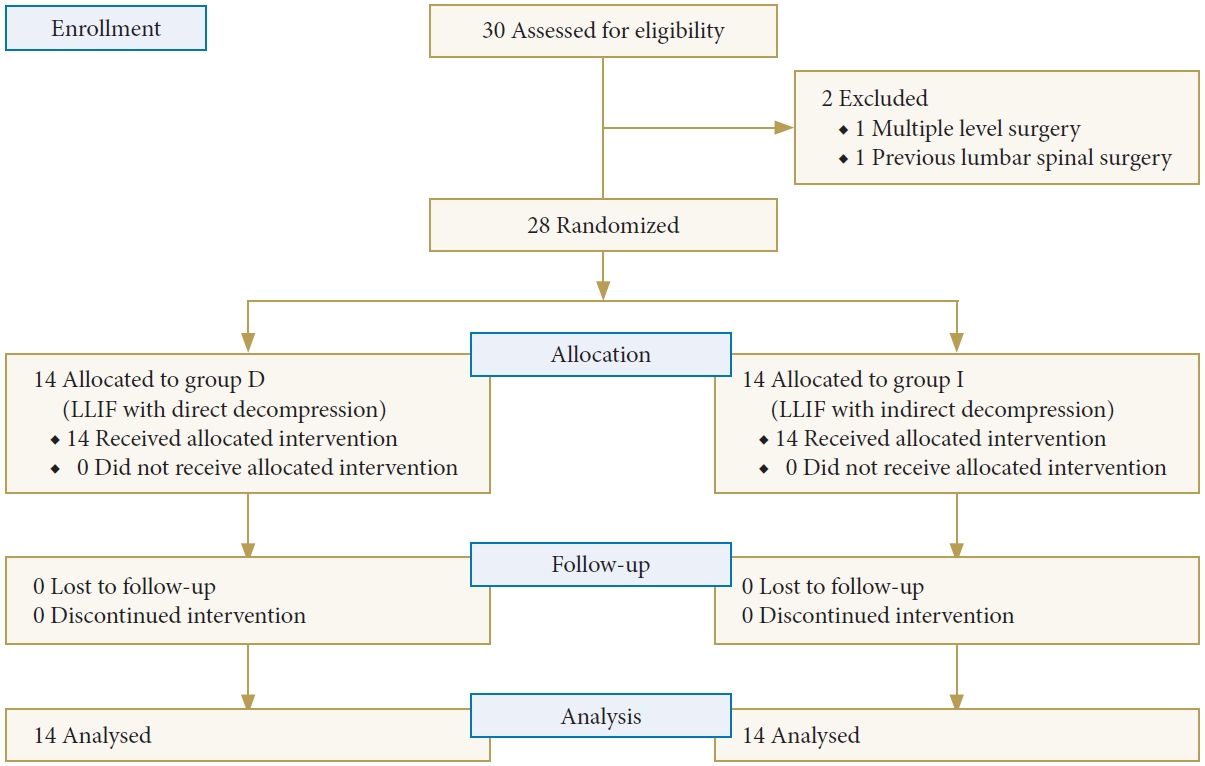

RESULTS

A total of 30 participants were initially enrolled in the study. However, one participant was excluded due to the need for multiple-level surgery, and another participant had a history of previous spinal surgery. Thus, a total of 28 participants were randomized, with 14 participants allocated to each group. All patients had completed followed-up examination for at least 12 months postoperatively (Fig. 4). The average age was 66.1± 6.8 years with a female predominance (18 of 28, 64.3%). Spondylolisthesis was the most common diagnosis (82.1%) and L4–5 was the most commonly operated level (89.3%). There were no significant differences in preoperative baseline characteristics between the 2 groups, including age, gender, diagnosis, and level of surgery. Preoperative VAS-L, VAS-B, and ODI were not significantly different between groups. Patient demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram for the recruitment and flow of participants through the trial. Group I, lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) with indirect decompression; group D, LLIF with direct decompression.

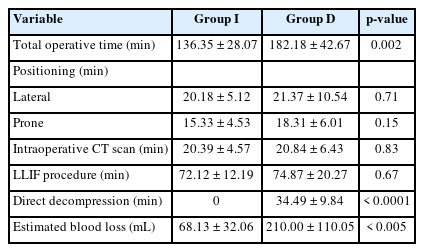

1. Perioperative Data

The total operative time for group I was significantly shorter than that of the LLIF in group D (136.35± 28.07 vs. 182.18± 42.67 minutes, p= 0.002). The average time required for direct decompression in group D was 34.49± 9.84 minutes. The operative time of each surgical step was shown in Table 2. LLIF with indirect decompression resulted in significantly lower estimated blood loss than LLIF with direct decompression (68.13± 32.06 vs. 210.00± 110.05 mL, p< 0.005).

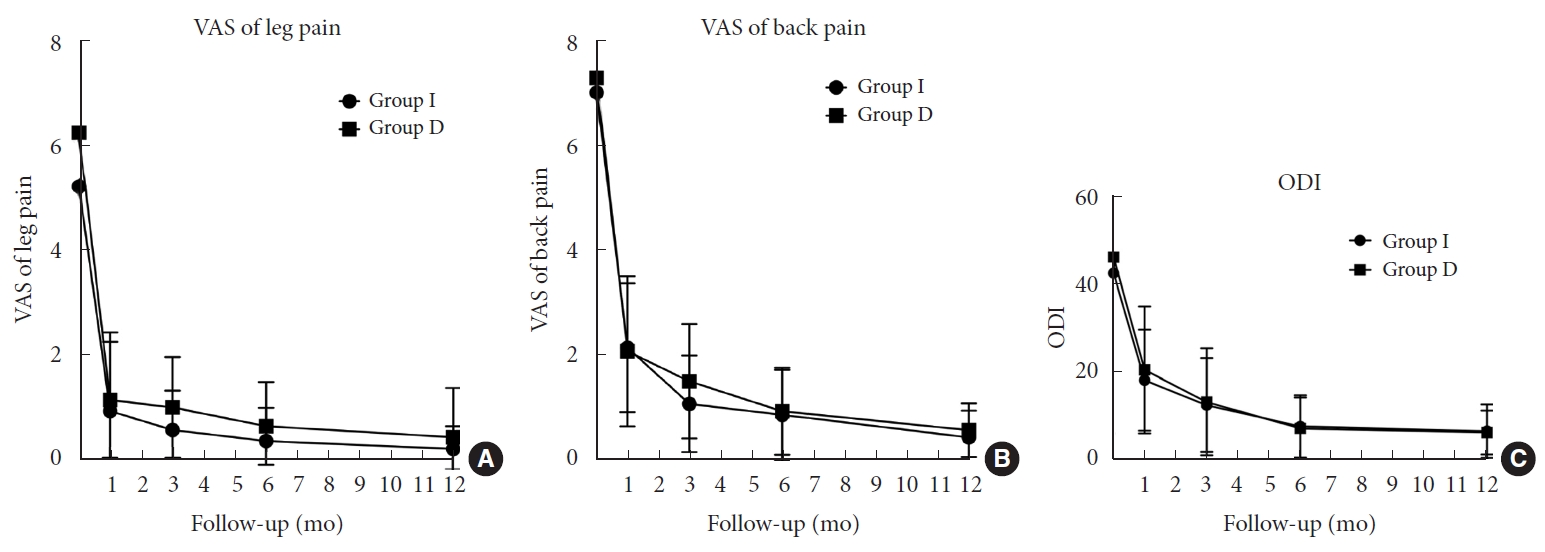

2. Patient-Reported Clinical Outcomes

Both groups demonstrated significant improvement in pain reduction and decreased disability after the surgery. However, there were no significant differences in the extent of clinical improvement between the 2 groups across any of the follow-up periods. In the final follow-up assessment, for VAS-L, while group I revealed a significant improvement of 4.93± 3.22, group D had comparable pain reduction of 5.57± 3.29 (p= 0.61). Similarly, VAS-B showed significant pain reduction of 5.86± 2.79 in group I and 6.36± 2.06 in group D (p= 0.59). Changes in ODI were also comparable between groups I and D, with improvements of 35.08± 13.84 and 39.05± 14.19, respectively (p= 0.46) (Fig. 5).

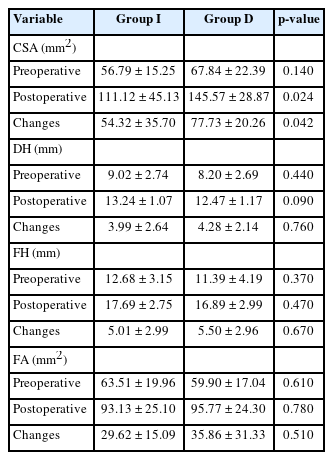

3. Radiographic Outcomes

Preoperative radiographic measurements did not differ between both groups. After the surgery, there was a significant improvement of all radiographic parameters in both groups, including CSA, DH, FH, FA, SL, and LL. Among these parameters, the increase in CSA was significantly higher in group D compared to group I (77.73± 20.26 mm2 vs. 54.32± 35.70 mm2, respectively, p = 0.042). The remaining radiographic parameters, however, did not reveal significant differences between the groups. Correspondingly, there were no differences in fusion grading as per the modified Bridwell criteria. When combining grades I and II fusion status, the overall fusion rate reached 96.4%. Detailed outcomes of these radiographic assessments are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Changes of size and area of spinal canal following LLIF with indirect decompression (group I) and with direct decompression (group D)

4. Complications

Our study did not encounter any major complications, such as vascular injury, neural injury, ureter injury, or infection. Among the participants, 3 individuals (10.7%) experienced transient thigh pain or numbness, which spontaneously resolved within 3 months following the surgery. Notably, none of the patients in group I necessitated subsequent additional posterior direct decompression. Furthermore, both groups did not reveal implant malposition, cage migration, significant cage subsidence, or infections. There was no reoperation surgery.

DISCUSSION

Our study indicated that there was no difference in clinical outcomes between LLIF performed with and without direct decompression. Remarkably, among patients who underwent indirect decompression alone, none required subsequent reoperation for additional posterior direct decompression. This finding underscores the effectiveness of indirect decompression achieved with LLIF surgery, particularly when performed on suitable surgical candidates. Therefore, additional direct decompression may not be necessary in the selected patients.

LLIF has been established as an effective treatment for patients with degenerative spine disease by providing indirect decompression to neural elements through ligamentotaxis mechanism [6]. However, the necessity of additional direct decompression via the posterior approach at the index level has been a subject of discussion [19]. Wang et al. [20] reported 9% incidence of indirect decompression failure that needed revision with direct decompression. Gabel et al. [11] identified predisposing factors for the need of direct decompression after LLIF including a free disc segment, facet cyst, osteoporosis, and severe spinal stenosis. Yingsakmongkol et al. [10] reported that low reducible DH, low postoperative DH, high-grade cage subsidence, and the use of anterolateral plate fixation were also risk factors of indirect decompression failure. These failure cases raised questions regarding whether, under appropriate indications, indirect decompression can provide similar outcomes compared to cases with additional direct decompression. Therefore, a comparison study with a control group is needed to address this controversy. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first randomized controlled trial to compare outcomes following LLIF with and without direct decompression under the same prerequisites.

In this study, we strictly followed the patient selection criteria that was published in the literature when recruiting patients as each criterion is based on specific rationales [1,10,11,19]. First, the significant pain relief when the patients are at rest in a supine position is essential. This phenomenon suggests that their symptoms can be alleviated when there is a dynamic disc space distraction, leading to an increased space within the spinal canal as the patient lies down, in contrast to an upright position. This mechanism resembles the ligamentotaxis effects achieved from LLIF procedure that indirectly decompress the spinal canal via adequate unbuckling of the ligamentum flavum and expansion of the neural foramen. Conversely, persistent pain despite resting in a supine position indicates a severe spinal canal stenosis where direct decompression becomes necessary to remove the significant pressure on the neural element [1,21]. Second, the presence of a DH discrepancy between supine and upright positions signifies the flexibility of the affected segment that facilitates the restoration of the DH when lying in a supine position, and thereby produces an effective indirect decompression effect [22]. Third, patients with significant weakness were excluded since this clinical finding usually indicated a severe nerve compression that might not be sufficiently relieved through indirect decompression alone. Lastly, surgical candidates must not have a static nerve compression from facet cyst or bony lateral recess since these lesions persistently compress the nerves and are less likely to be relieved with the effect of indirect decompression by ligamentotaxis mechanism [23-25].

By employing these criteria for patient selection, we observed comparable significant clinical improvements in both groups. There was no indirect decompression failure necessitating revision surgery. Although direct decompression results in a more significant increase in spinal canal space, there were no differences in pain and disability improvement when compared to patients who did not undergo posterior decompression. This suggests that LLIF provided an adequate decompression effect to relieve symptoms by mechanisms of ligamentotaxis, unbuckling ligamentum flavum, reduction of bulging discs, and restoring disc and FH [1,26]. Moreover, obviating the need for posterior decompression also reduced invasiveness of the operation, leading to reduced blood loss and shortened the procedure duration. Given the comparable effectiveness of overall surgical outcomes and the advantages of minimally invasive approach, LLIF with indirect decompression alone may be considered as a favorable option for carefully selected patients.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size is small since we strictly followed the selection criteria to find surgical candidates. We believed that, in a larger cohort, a greater range of complications may be observed, such as pseudarthrosis, cage subsidence, or dural tears during direct decompression procedure. Second, blinding of the surgeon to the allocated treatment (with or without additional direct decompression) was not achievable. This lack of blinding of the surgeon could introduce bias, potentially influencing decisions made during the procedure. For example, when performing indirect decompression with LLIF, surgeons might opt for a higher cage to achieve greater decompression effect, or may try to remove a bulging disc from an anterior approach to decompress the nerve. Third, the twelve-month follow-up period might be insufficient to detect long-term clinical outcomes or complications, including adjacent segment disease that associated with worsening symptoms and revision surgery. Therefore, further studies with extended follow-up and larger sample sizes are imperative. Lastly, it is crucial to note that this study results could only confirm the comparable efficacy of LLIF with indirect decompression and outline how we select surgical candidates. However, it does not provide definitive indications for when direct decompression is mandatory.

CONCLUSION

With a careful patient selection based on our implemented criteria, indirect decompression through LLIF results in comparable clinical improvement to LLIF with additional direct decompression over a midterm follow-up period. These findings imply that, for an appropriate candidate, direct decompression in LLIF might not be necessary since the ligamentotaxis effect achieved through indirect decompression appears sufficient to relieve symptoms, while also reducing blood loss and operative time.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

WL and WS have received speaker and consultant honoraria from Medtronic company. Other authors declare they have no financial interests.

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: WL, KJ, VK, WY, WS; Data curation: CT, PP; Formal analysis: CT, TT; Methodology: WL, KJ, PP, WS; Project administration: WL, WS; Visualization: KJ, WY, TT; Writing - original draft: CT, KJ; Writing - review & editing: WL, KJ, WS.