Lumbar Disc Herniations 'To Operate or Not' Patient Selection and Timing of Surgery

Article information

Abstract

At times lumbar disc herniations present a quandary to the spine surgeon in regards to the most appropriate intervention and a need to optimize medical and surgical therapies. We discuss a case of ours and our experience in treating this common spinal pathology, along with a commentary on the article published by Kim et al. entitled 'Spontaneous regression of extruded lumbar disc herniation: three cases report in Korean J Spine. 2013 Jun;10(2):78-81.'

We would like to elaborate on some of the issues brought up by Kim et al.15) in their article in Korean Journal of Spine regarding spontaneous disk regression in a recent publication entitled 'Spontaneous regression of extruded lumbar disc herniation: three cases report.' 2013 Jun;10(2):78-81.

Lumbar disc herniations remain one of the most common reasons for a visit to the spine surgeon, being a significant contributor to low back pain and lower extremity radicular syndrome. The therapeutic approach ranges from conservative medical interventional management to surgery. Although there is a significant body of literature on the various management options and outcomes, as predicted, there is no uniform consensus regarding the most appropriate interventions and specifically the timing of surgical intervention. At symptom onset, in the absence of any neurological deficits, conservative medical treatments are initially attempted and have known therapeutic efficacy. Various studies have also confirmed the effectiveness of surgery in the initial management of lumbar disc herniations. In the absence of symptoms resolution, surgical intervention is usually performed anywhere between two and twelve months following the onset of pain. In our experience the presence of neurological deficits at with the onset of radicular such as muscle weakness, cauda equina syndrome or a progressive deficit while being medically managed, make early surgical intervention essential and give the patient the best opportunity for neurological recovery22).

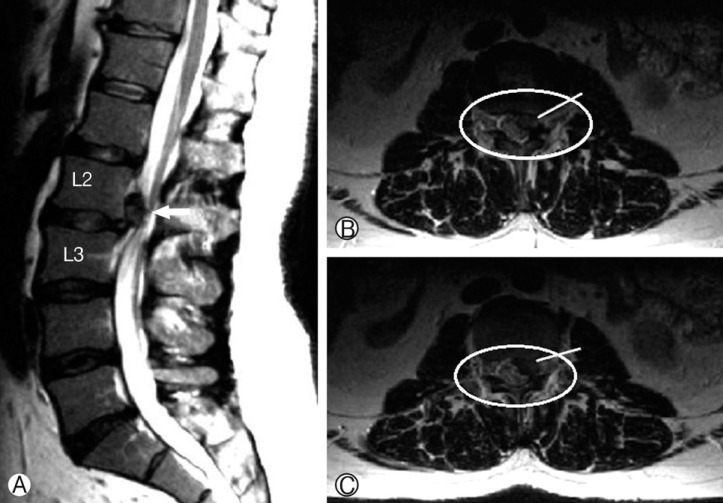

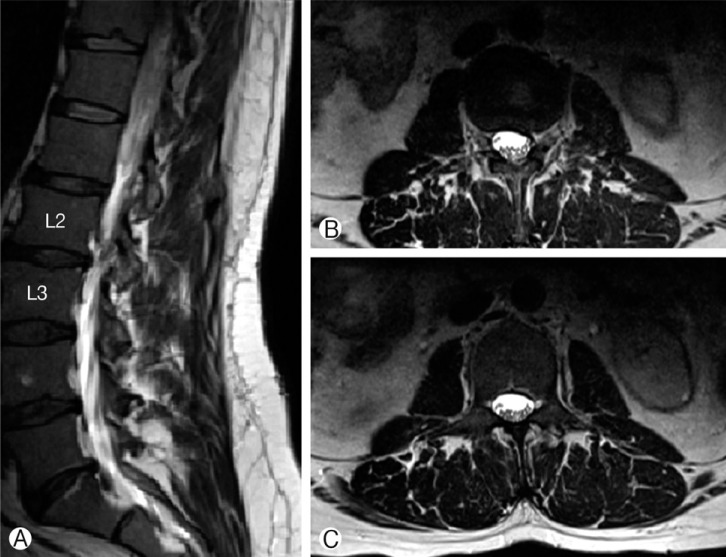

We recently had 52 year old gentleman presented with a lumbar disc herniation and radicular pain without any focal neurological deficits. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his lumbar spine revealed an L 2/3 disc herniation with a large extruded fragment (Fig. 1A, B & C). His associated co-morbidities included smoking, diabetes and obesity. We opted to manage this patient conservatively with pain medications, initial rest for no longer than 48-72 hours followed by a gradual physical therapy rehabilitation program. We decided to on a subsequent clinical follow-up at 12 weeks and then 6 months depending on the nature of his symptoms and ability to continue his daily activities. His radicular pain had gradually subsided at 9 months at which time we repeated the MRI of his lumbar spine. The MRI revealed a resolution in the extruded fragment without any neural compression and the absence of pain (Fig. 2A, B & C).

(A) Sagittal T2 WI-MRI reveals an L2-3 herniated disk fragment migrating upwards. (B) Axial T2 WI reveals a left sided paracentral extruded disk fragment. (C) Axial T2 WI at the level of the L2/3 disk space revealing the extruded fragment almost encroaching the foramen.

(A) Follow-up T2 WI MRI sagittal images revealing resolution I regression at the L2/3 disk level (B & C) Axial T2 WI revealing absence of any disk fragment across the L2/3 disk levels.

Kim et al. have published a report of 3 cases that were managed conservatively in their practice with good symptomatic and radiological resolution15). We concur with the authors in the rarity of this finding in practice, although we often do not image patients who have had resolution of their radicular symptoms. In our practice, a majority of our patients who have an extruded or trans-ligamentous herniated fragments that remains within the confines of the spinal canal, with minimal foraminal, trans-foraminal or far lateral extension are ideal candidates to get an initial trial of conservative medical interventional therapies. As will be noted in the MRI imaging seen in the 3 cases reported by Kim et al. as well as our case, the patients that have shown regression have fragments within the spinal canal. In a more recent report by Kim E et al.14), in the 3 cases they reported, one patient developed spontaneous resolution as early as 2 months, whereas another did not have any evident disc identified during surgery. A review of their cases reveals similar MRI findings in their cases. There have been other reports in literature describing spontaneous regression of lumbar discs with various theories for this infrequently seen phenomenon1,2,10,13,19).

The dilemma in patient selection occurs when a patient presents with sciatica in the absence of a neurological deficits that is associated with a large herniated lumbar disc fragment. If surgery is the treatment path, what is the ideal time to intervene in order to give the patient the best outcome? Has early surgery proven to give better results or is it better to delay surgery? When we review literature regarding the natural history of lumbar disk herniation with and without surgery, initial surgery appears to provide good symptomatic relief, however outcomes at 2 years following surgical treatment vs. no surgery (medical interventional modalities) interventional modalities remain the same3,4,5,7,8,11,16). When we review the time to surgical intervention, literature is replete with a number of studies addressing the issue of surgical timing6,9,12,17,18,21). Although there is a wide range of between 2 and 12 months as being best for surgical intervention, we tend to intervene earlier in far lateral and foraminal disc herniations. For central and paracentral disk herniations we recommend waiting as long as 9 months with medical interventional management. However if the patients pain is unbearable and significantly affects their activities of daily living, quality of life and ability to return to work, earlier intervention at around 5-6 months would be of benefit. This may also prevent the development of a chronic pain syndrome which could lead to a cycle unresponsiveness to later surgical intervention. Earlier intervention at 6-8 weeks may be an option in cases of worsening pain with the onset of a new neurological deficit. In our patient it took 9 months for the disk and pain to resolve, however the patient's pain profile during follow-up had a diminishing trend with more control of his pain. If at 6 months the same patient was symptomatically worse we would have offered surgery. In addition to timing of surgery there are a number of other variables like age, weight, body mass index, smoking, physical activity levels that need to be taken into account, and affect the outcomes of disk surgery20).

Our recommendations are for surgical intervention lie anywhere between 6 months to a year taking into accounts all the patient variables and image findings. Although some surgeons would prefer earlier intervention at 6 weeks, we feel that in the absence of neurological deficits 6 months gives the patient time to try out various medical/interventional therapies. Beyond a year, we generally repeat MRIs of the lumbar spine as degenerative disk disease is a dynamic process and changes over this time can alter our surgical strategy. Acute or emergent surgeries in our practice are recommended in the patient with neurological deficits along with pain at initial presentation or during the course of medical interventional management. The ongoing debate indicates that there is more work ahead and larger randomized trials with similar patient profiles may help answer this simple yet baffling question.