Use of Opioids and Other Analgesics Before and After Primary Surgery for Adult Spinal Deformity: A 10-Year Nationwide Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

To report the 1-year pre and postoperative analgesic use in patients undergoing primary surgery for adult spinal deformity (ASD) and assess risk factors for chronic postoperative opioid use.

Methods

Patients > 18 years undergoing primary instrumented surgery for ASD in Denmark between 2006 and 2016 were identified in the Danish National Patient Registry. Information on analgesic use were obtained from the Danish National Health Service Prescription Database. Use of analgesics was calculated one year before and after surgery for each patient, per quarter (-Q4 to -Q1 before and Q1 to Q4 after). Users were defined as patient with one or more prescriptions in the given quarter.

Results

We identified 892 patients. Preoperatively, 28% (n = 246) of patients were opioid users in -Q4 and 33% (n = 295) in -Q1. Postoperatively, 85% (n = 756) of patients were opioid users in Q1 and 31% (n = 280) in Q4. Proportions of users of other analgesics (paracetamol, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants) were stable before and after surgery. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug decreased postoperatively by 40% (-Q1 vs. Q4). 26% of patients had chronic preoperative opioid use (one or more prescriptions in each -Q2 and -Q1) and 24% had chronic postoperative use (prescription each of Q1–Q4). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed age increment per 10 years and preoperative chronic opioid use as risk factors for chronic postoperative opioid use.

Conclusion

One year after ASD surgery, opioid use was not reduced compared to preoperative usage.

INTRODUCTION

Within the last 20 years, there has been an exponential use of prescriptive pain medication in Denmark, especially of opioids [1]. Opioids are very useful for treatment of acute pain but continued opioid use for chronic pain has been associated with reduced quality of life, increased morbidity, increased pain intensity, and pain-related disability [2-10].

Besides the improvement of disability and decrease of curve progression, one of the main indications for adult spinal deformity (ASD) surgery is pain reduction [11]. However, the knowledge of opioid use before and after surgery for ASD is very limited. The utilization of pain medication before and after surgery in general has been examined and the risk of opioid use postoperatively is considerable [2-4,12]. Armaghani et al. [13] reported that 55% of patients undergoing spine surgery used opioids prior to surgery. Schoenfeld et al. [14] concluded that more intense surgical spine intervention increased the likelihood of sustained opioid use. Furthermore, previous studies have found that preoperative opioid users before ASD surgery are likely to continue to use postoperatively [15,16]. We have previously investigated early morbidity following first time ASD surgery and found that postoperative pain management was a considerable challenge [17]. To improve the treatment and recovery after ASD, it is important to understand the prescription pattern of analgesics before and after ASD surgery. To our knowledge, such study has not been conducted exclusively in first time ASD surgery patients. The aim of this study was to describe the use of opioids and other analgesics at 1 year prior and 1 year following first time ASD surgery. We hypothesized that the prescription of analgesic medication would decrease in the year following ASD surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In Denmark, all citizens have a personal, unique social security number (CPR number) used in all contacts with the health care system, both public and private. All public health care is tax funded and free of charge. The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) collects data from all in and out patient visits throughout the entire country [18]. The DNPR registers each patient’s CPR number, dates of admission and discharge, discharge diagnoses, and/or procedure codes classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, eighth edition (ICD-8), until the end of 1993, and tenth edition thereafter (ICD-10). To receive reimbursement, all hospitals have to report to the DNPR, and enabling a complete nationwide follow-up [19-21].

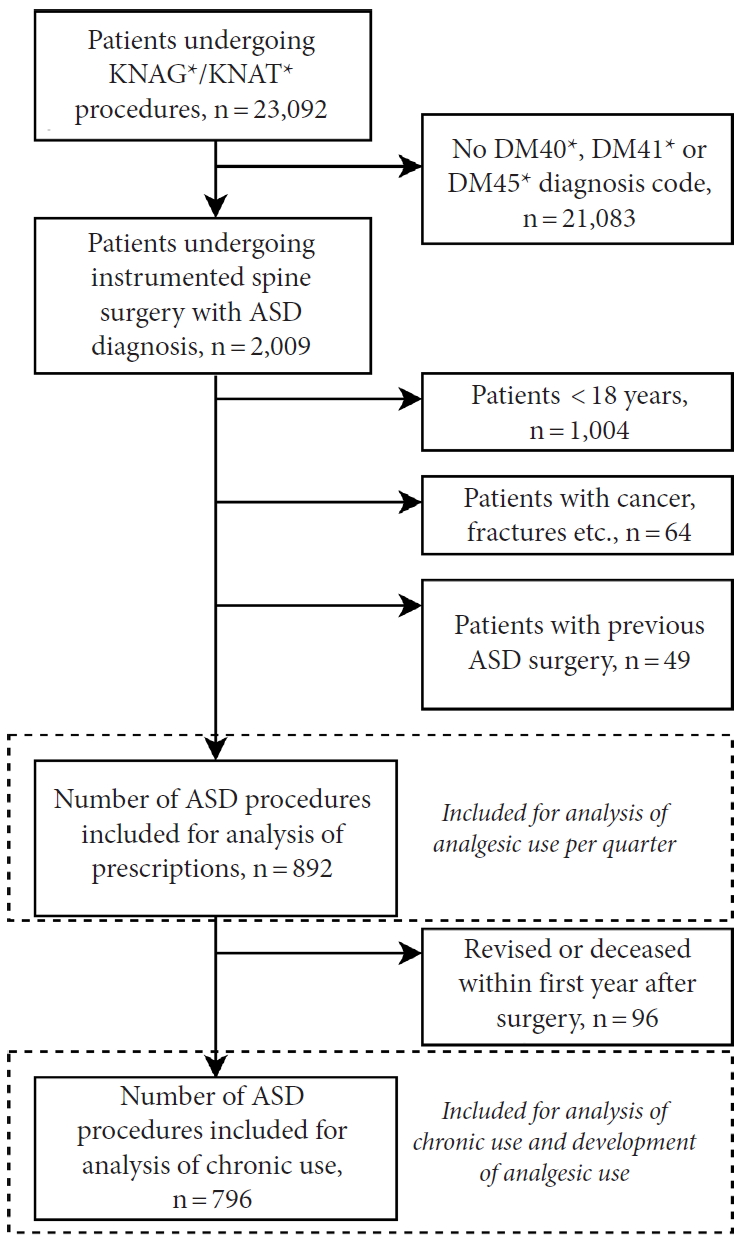

Patients undergoing instrumented spine surgery (procedure codes KNAG/KNAT, see Supplementary material 1) with concurrent and relevant diagnosis of either DM40 (Kyphosis/Lordosis), DM41 (Scoliosis) or DM45 (only Mb. Bechterew) between January 1st, 2006 and December 31st, 2015 were included [18]. In a previous study on this patient cohort, we validated this selection method [17]. A 10-year wash-out period was introduced to only include primary ASD surgeries. Patients < 18 years at the time of surgery, with columnar cancer/metastases, spinal infection, concurrent spinal fracture, or other spinal trauma diagnosis were also excluded (Fig. 1).

To assess the comorbidity burden, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [22] was calculated for each patient. All prior contacts since 1977 (both in- and outpatient) to index surgery, including all diagnosis codes, were collected for each patient from the DNPR. The DNPR has been validated as a reliable source for calculating CCI score [23]. For list of diagnosis codes used for each CCI category see Supplementary material 2. Patients were classified according to 1 of 3 levels of CCI score: low (CCI score of 0), medium (CCI score 1 or 2), or high (CCI score ≥ 3).

Information regarding all reimbursed prescription medicine from all community pharmacies in Denmark is recorded in The Danish National Health Service Prescription Database (DNHSPD) with nationwide coverage since 2004. All prescriptions are identified by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system (ATC codes). The DNHSPD includes name and brand of the drug, quantity, formulation, date of refill, codes identifying the prescribing physicians, and the dispensing pharmacy [24]. Information on hospital dispensaries is not included in the DNHSPD. Following ATC codes (including all sub codes) were included in this study: M01A (anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products, nonsteroids), N01AH (opioid anesthetics), N02A (opioids), N02B (other analgesics and antipyretics), N03A (antiepileptics), N06A (antidepressants), N07BC02 (methadone), and R05DA04 (codeine). See Supplementary material 1 for list of all ATC codes. All analgesics, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants in Denmark require prescriptions from a physician. Before January 1st, 2013, paracetamol (500 mg) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (200 mg) in 100-tablet packages was available to purchase without prescription. After January 1st 2013, only 10-tablet packages of paracetamol/NSAID are sold without prescription [25]. Thus, practically all analgesics sold are tracked through DNHSPD.

Prescriptions were identified for the following periods (quarter, Q): -Q4 (12–9 months before surgery), -Q3 (9–6 months before surgery), -Q2 (6–3 months before surgery), -Q1 (3 months prior to surgery), Q1 (3 months after surgery), Q2 (3–6 months after surgery), Q3 (6–9 months after surgery), and Q4 (9–12 months after surgery). The patients were identified as opioid users in each period if they redeemed one or more of any opioid prescriptions in the given period. Opioid nonusers did not redeem any opioid prescriptions in the given period. Use of other analgesics was calculated the same way. Results are presented for each drug and drug group (NSAIDs, paracetamol, opioids, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and other). The dose analysis was not done.

Patients were classified as “chronic preoperative users” if they redeemed one or more opioid prescriptions in each of quarters -Q2 and -Q1. Likewise, patients were classified as “chronic postoperative users” if they redeemed one or more opioid prescriptions in each of quarters Q1 to Q4.

For the analysis of development of analgesic use at Q1–Q4 patients who underwent revision surgery that the inserted spinal instrumentation removal, elongated or otherwise manipulated or decreased patients were excluded.

1. Statistical Analysis

All data were tested for normal distribution using Q-Q plots and histograms. Means are reported with standard deviation (SD) and medians are reported with interquartile ranges. Characteristics of the study population of ASD surgery patients were presented overall and by chronic and nonchronic preoperative opioid use. The distributions of sex, age, CCI scores, and preoperative chronic use of antidepressants and anticonvulsants were by tabulating as number and percent of patients. Proportions of drug use were calculated as number of users/total number of patients at risk in each quarter. Analysis of potential risk factors associated with chronic postoperative opioid use was performed using multivariate logistic regression calculating crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In the multivariate regression model, we adjusted for sex, age, CCI scores and preoperative chronic use of opioids, antidepressants and anticonvulsants. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests. All statistical analyzes were done using R, ver. 3.3.3 (R Development Core Team, 2011, Vienna, Austria).

2. Ethics

As this study was noninterventional, no ethical approval was required. Permissions were acquired from the Danish Data Protection Agency (The Capital Region of Denmark, journal number 2012-58-004) to store data on patients and the Danish National Board of Health (journal number 3-3013-1746/1) to retrieve medical records.

RESULTS

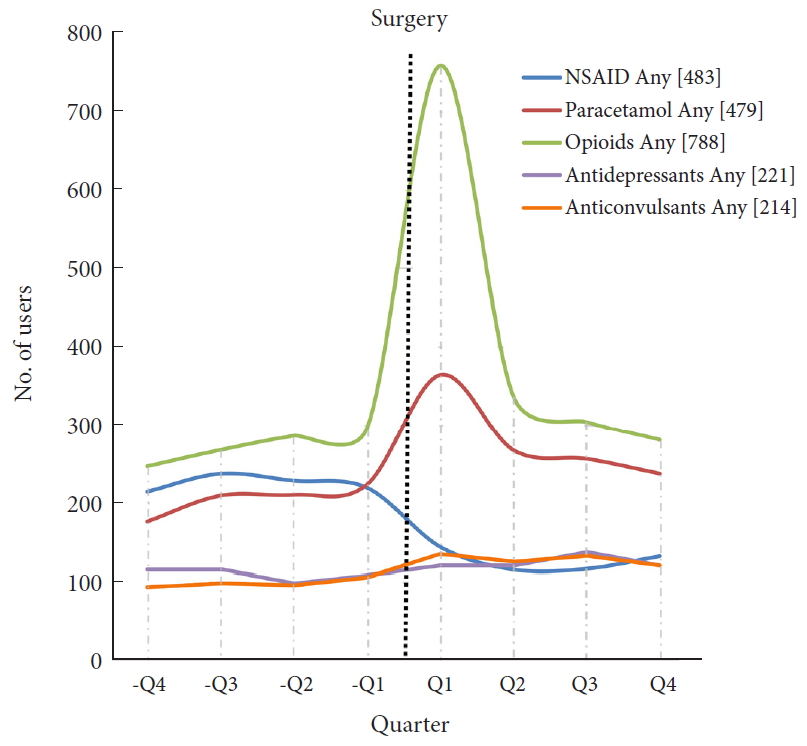

A total of 892 patients undergoing primary ASD surgery were included (Fig. 1). Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. In total, 28% of patients (n = 246) were opioid users in -Q4 and this increased to 33% (n = 295) in -Q1. After surgery, 85% of patients (n = 756) were opioid users in Q1 and this decreased to 31% (n = 280) in Q4. Hence, the percentage of patients with opioid use was at the same level 1 year before and 1 year after surgery. Tramadol, Contalgin, and Oxycodone were the major opioid drugs prescribed in the postoperative period.

Demographic data for the 892 patients undergoing first time adult spinal deformity surgery, overall and divided into preoperative chronic opioid user and nonuser

Among all ASD patients, 25% were NSAIDs users in -Q1 (n = 220), which changed to 15% (n = 132) in Q4. In addition, 25% (n = 224) were users of paracetamol in -Q1, which changed to 27% (n = 238) in Q4.

There were 12% of antidepressants and anticonvulsants users (n = 107 and n = 105, respectively) in -Q1 and 13% (n = 120 and n = 119, respectively) in Q4. Number of users for all drugs in each quarter are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 2 shows the number of users per drug group per quarter.

In total, 28% (n = 246) of all patients were categorized as preoperative chronic opioid users. These patients were older (median age 61.0 vs. 44.0, p < 0.001), had higher comorbidity burden (39.4% medium and 11.8% high vs. 26.5% and 5.4%, p <0.001) and had more chronic antidepressant and anticonvulsant use (21.1% and 17.5% vs. 5.7% and 7.1%, both p < 0.001) (Table 1).

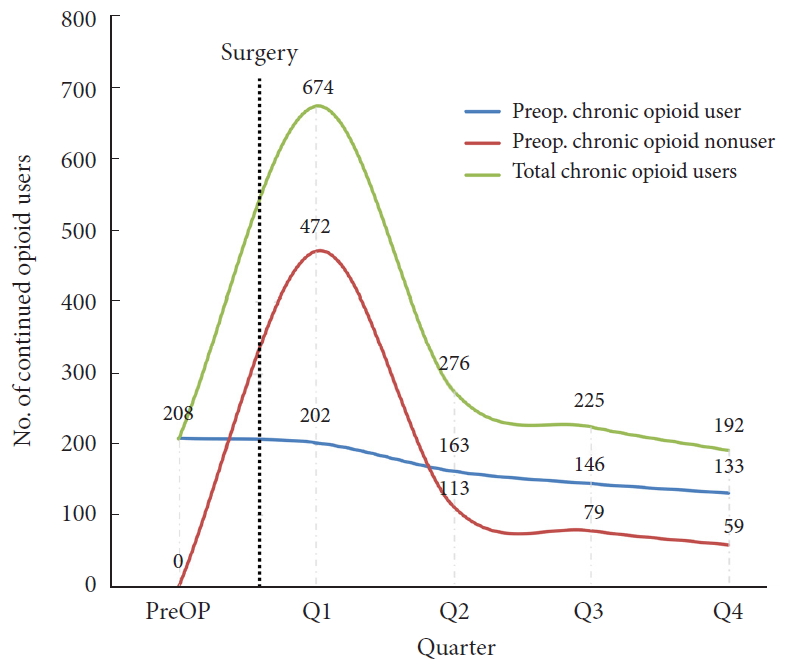

Development of analgesic use postoperatively is shown in Table 3 (n = 796, revised and deceased patients excluded). Of the 26.1% (n = 208) chronic preoperative opioid users, 63.9% (n = 133) remained chronic users after surgery. Of the 588 patients with no chronic opioid use before surgery, 10.0% (n = 59) developed chronic opioid use postoperatively. Fig. 3 illustrates the continued postoperative opioid (use in each quarter) use for preoperative chronic users and nonusers.

Development of analgesic use after primary adult spinal deformity surgery for the 796 patients without revision or death within 1-year of follow-up

Number of patients with continued postoperative opioid use. Divided by preoperative chronic user and nonuser. Preop., preoperative.

Preoperative chronic NSAID use was seen in 17.6% (n = 140) of patients, and 22.9% (n = 32) of these remained chronic users postoperatively. Chronic users of antidepressants (9.9%, n = 79) and anticonvulsants (9.5%, n = 76) preoperatively had similar postoperative development; 54.4% (n = 43) and 64.5% (n = 49) remaining chronic users postoperatively.

Based on univariate logistic regression, male sex was associated with lower risk of being a chronic postoperative opioid user (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.45–0.93), whereas age increment per 10 years (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.39–1.69), medium comorbidity burden (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.28–2.59), preoperative use of anticonvulsants (OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.66–4.40), antidepressants (OR, 2.84; 95% CI, 1.76–4.58), and opioids (OR, 15.90; 95% CI, 10.76–23.49) was associated with increased risk of being chronic postoperative opioid user. In multivariate logistic regression mutually adjusted for all risk factors, only age increment per 10 years (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.15–1.46) and preoperative chronic opioid use (OR, 11.76; 95% CI, 7.77–17.79) were still associated with increased risk of being chronic postoperative opioid user (Table 4).

A dropout analysis was conducted on the 84 patients (9.4%) who underwent a revision procedure within the first year or deceased in the study period. Of these, 41.7% (n = 35) were chronic opioid users preoperatively and 46.4% (n = 39) had chronic postoperative opioid consumption. Fourteen patients (1.6%) died within the follow-up year, and 3 of these (21.4%) were preoperative chronic opioid users.

DISCUSSION

The main finding in this nationwide cohort study before and after first time ASD surgery was that the overall opioid use remained unchanged the first year after surgery.

Opioid use before spine surgery has been reported in 39%, 55% of patients [13,16]. Schoenfeld et al. [16] reported only 9% of patients to continue opioid use 6 months after surgery, but in patients with less invasive spine surgery than in our study. We found that use of other potential analgesics (paracetamol, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants) was also practically unchanged after surgery. Only NSAID use decreased from 25% in -Q1 to 14.8% in Q4. This may reflect the reluctance for spine surgeons to prescribe NSAIDs due to the risk of pseudarthrosis [26]. Thus, the current results could indicate that ASD surgery is not having the expected effect on pain nor reduction in analgesic use.

Chronic preoperative use of opioids was observed in 26% of patients, when patients who underwent revision or deceased during follow-up were excluded. We excluded revision surgeries to analyze only surgical “successful” procedures and deceased patients to have complete, 1-year follow-up on all patients. The current results confirm the findings from a recent study by Sharma et al. [15], reporting that 36% of patients undergoing spinal fusion for scoliosis had chronic opioid use preoperatively. However, they used a different definition of “chronic use” and did not include prescription of nonopioids. Schoenfeld et al. [16] reported only 3% of patients to be chronic preoperative users before 4 types of different spine surgery (fusions included). They defined preoperative “chronic use” as prescriptions for opioids ≥ 6 months, very similar to the definition used in our study. This large difference might be attributed to the fact that Schoenfeld et al. [16] also included patients with less severe spinal conditions.

In our study the percentage of chronic opioid users only decreased 2% from pre- to postoperatively (Table 3). This is despite our conservative classification of chronic postoperative users compared to previously published studies. Previously, postoperative chronic use has been reported in 44% of spinal surgery patients at 12 months [13] and 28% at 15 months postoperatively [15]. Though we observed a 36% discontinuation of opioids in the chronic preoperative users, the 10% nonchronic who became chronic opioid users after surgery is a major challenge. This is even without the patients undergoing revision, as they were excluded. For a nonchronic opioid user before surgery, a chronic opioid use after could be considered a nonsuccessful surgical intervention. Our results are in contrast to a study by Schoenfeld et al. [14] in opioid nonusers undergoing spine surgery; they concluded that spine surgery is not causing long-term opioid use. From Fig. 3, a decreasing trend of continued opioid use in both groups (and total) is observed throughout the postoperative quarters. It could be hypothesized, that if follow-up was prolonged this trend could continue and thus lower number of chronic postoperative users considerably. However, studies with longer follow-up are needed to investigate this.

When comparing preoperative chronic and nonchronic opioid users, chronic users are older at time of surgery, more are female, comorbidity burden is higher, and use of antidepressants and anticonvulsants is higher (Table 1), in line with previous results [15,16]. Higher age, higher comorbidity burden, and higher intake of antidepressants and anticonvulsants could suggest that the more “vulnerable” patients are using opioids before surgery. In a multivariate analysis, only age increment per 10 years (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.15–1.46) and preoperative chronic opioid use (OR, 11.76; 95% CI, 7.77–17.79) were associated with postoperative chronic opioid use. Preoperative chronic opioid use has previously been reported as strong predictor for postoperative continued use after spine surgery [14,15]. Mental disorders and preoperative use of antidepressants have also been associated with increased risk of postoperative opioid use in previous studies [13,14], however we did not find this.

The results of our study suggest that pain management in ASD surgery should be revised. Especially since chronic use of opioids for nonmalignant pain is related to several side effects; hormonal dysfunction [6,27], cognitive impairment [27], tolerance [10], addiction [28], general increase in risk of morbidity [6,9], and mortality [29-31]. Furthermore, a study by Krebs et al. [32] showed that long-term opioid treatment for back pain was similar to nonopioid pain treatment. Introduction of an opioid-sparing regime in the 6 months leading up to surgery has been suggested by Armaghani et al. [13]. This could potentially also help to mitigate the early postoperative morbidity after spine surgery associated with preoperative opioid use [33].

This study improves the knowledge of use of opioids and other analgesics before and after ASD surgery. The strength of the present study is a large, up-to-date, cohort of consecutive, and unselected ASD patients. Our study is based on data from nationwide registries with very high data completeness [20,24]. As almost all analgesics require prescription and are registered in the DNHSPD, practically no prescriptions of NSAIDs, paracetamol, opioids, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants are undetected.

The limitations of our study are the absence of indication for prescription in the DNHSPD, the lack of dosage information, and the lack of ability to assess the actually consumed dose of each prescription. We assumed that prescriptions were for ASD related pain and that each filled prescription was used. Another limitation is the lack of information on over-the-counter sale of NSAIDs and paracetamols. However, as these are only sold in 10 pill containers in Denmark without prescription, it is unlikely to influence our results. Furthermore, the present study does not include health-related quality of life measurements before and after surgery, and this must be included in the overall assessment of the possible beneficial effects of ASD surgery.

CONCLUSION

We found that use of opioids and other analgesics were similar before and after primary ASD surgery. Distribution of chronic opioid user before and after surgery was similar to that before surgery. Furthermore, we found chronic preoperative opioid use and increased age to be significantly associated with chronic opioid use postoperatively. These results call for further attention to pain management in ASD surgery patients. The results also indicate that special attention should be directed at reducing opioid use before and after ASD surgery – especially in chronic opioid users.

Notes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material can be found via https://doi.org/10.12965/ns.1938106.053.