- Search

|

|

||

Abstract

Objective

The surgical treatment of lower cervical facet dislocation is controversial. Great advancements on reduction techniques for lower cervical facet dislocation have been made in the past decades. However, there is no article reviewing all the reduction techniques yet. The aim is to review the evolution and advancements of the reduction techniques for lower cervical facet dislocation.

Methods

The application of all reduction techniques for lower cervical facet dislocation, including closed reduction, anterior-only, posterior-only, and combined approach reduction, is reviewed and discussed. Recent advancements on the novel techniques of reduction are also described. The principles of various techniques for reduction of cervical facet dislocation are described in detail.

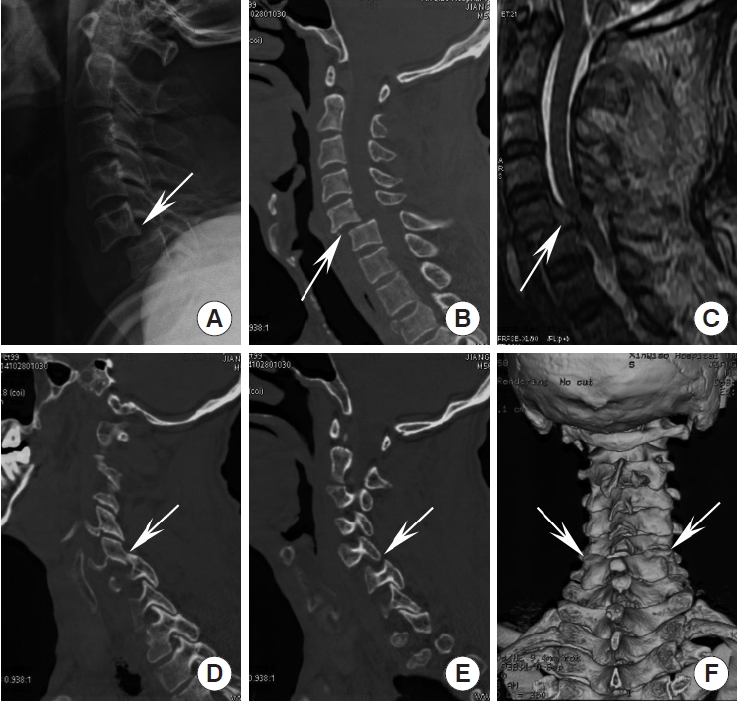

Lower cervical facet dislocation is a common spinal trauma caused by flexion-distraction force that usually results in damage to the 3-column structure, as well as vertebral dislocation, facet locking, and intervertebral disc destruction (Fig. 1). The treatment of lower cervical facet dislocation is generally recognized as reduction, decompression, fixation, and fusion. Early reduction can reduce the compression of the spinal cord, which is particularly important for patients with incomplete spinal cord injury. Since Walton et al. [1] first reported closed reduction by manipulation of cervical spine deformity caused by facet dislocation in 1893, great advancements have been made in reduction techniques, especially in recent years. In the present study, we review all reduction techniques, including traditional, popular, and novel techniques. In general, the reduction techniques are categorized into 4 main types: closed reduction, anterior alone, posterior alone, and combined approach techniques.

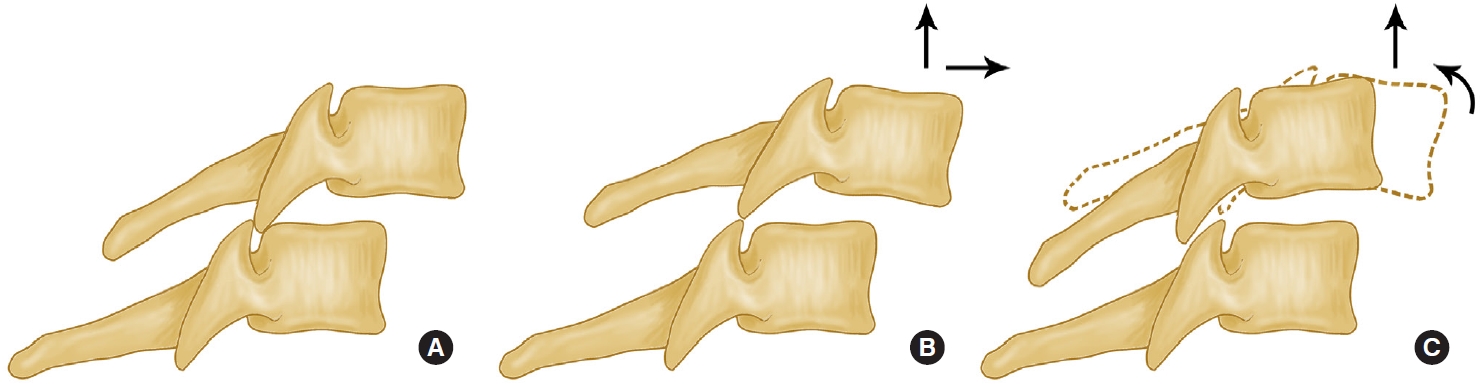

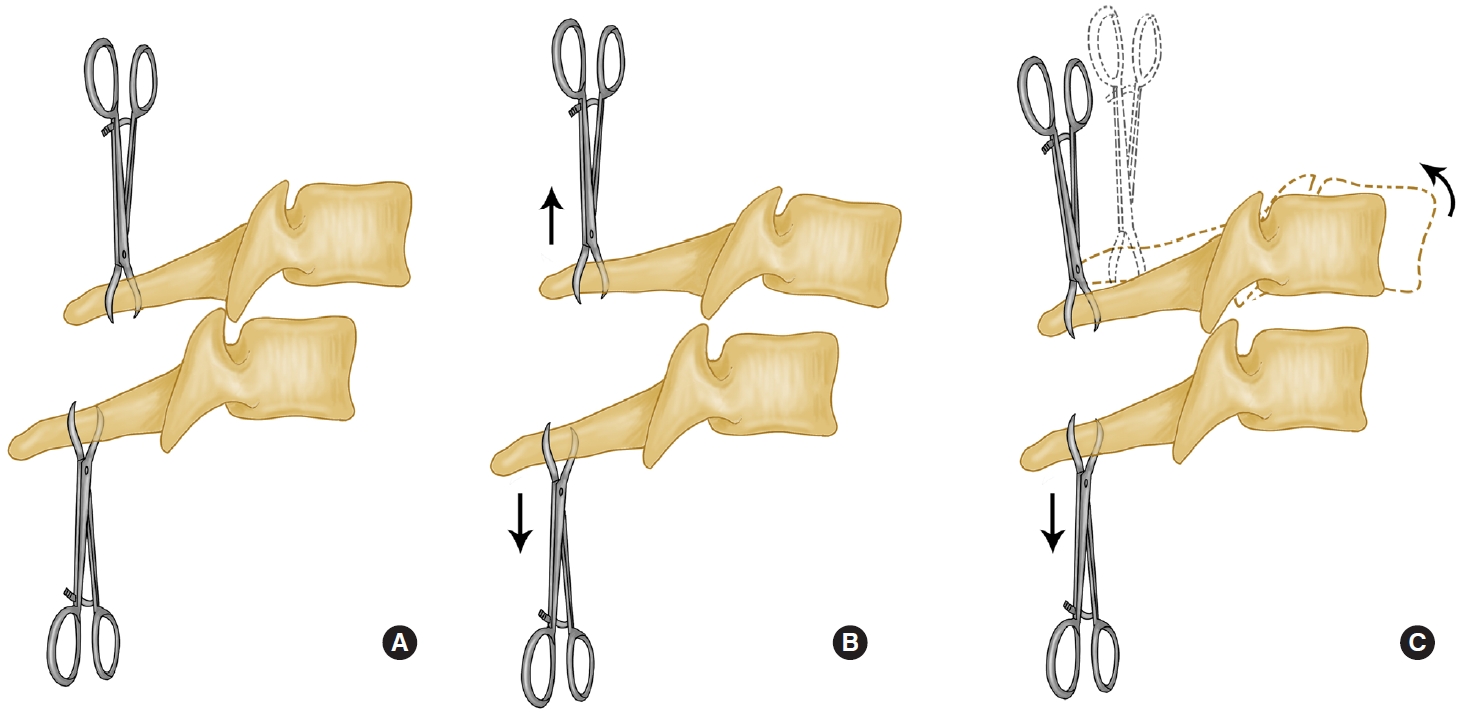

Close reduction was the initial technique for lower cervical facet dislocation. After Walton et al. [1] first described closed reduction by manipulation of cervical facet dislocation in 1893, Crutchfield et al. [2] introduced tongs for in-line traction-reduction in 1933. Thereafter, closed reduction of the cervical spine using head traction has been used for many years and reported as an effective treatment for many cervical facet dislocations [3-25]. Although the technique of manipulation varies from surgeon to surgeon, the basic procedure is a gradually traction, followed by anterior rotation and lateral flexion away from the side of the dislocated facets. while the locked facets have been disengaged, rotation is carried out in the opposite direction. As soon as a click is heard or felt, the neck is extended (Fig. 2).

Although the principle of closed reduction is basically the same, there are also some differences and controversies in various literature views. Firstly, the weights required to be traction reported in the previous literature were different [26-28]. Reindl et al. [27] reported that all patients were treated with Gardner-Wells traction, starting with 5 kg+2.5 kg/level of injury below C1. This was followed by addition of 2.5 kg every 30 minutes until reduction was achieved, to a maximum of 50% estimated body weight for 1 hour. In the cases report of Tumial├Īn et al. [24], an initial traction weight of 9.1 kg was applied, followed by an increase of 4.5 kg per hour. Once 27.2 kg was reached, the lateral radiograph was suggestive of reduction. Miao et al. [25] retrospectively analyzed 40 patients. The initial traction weight was 5 kg, and if the weight reached 15 kg, closed reduction could be completed in most patients (38 cases, 95%). This difference may depend on the state of the articular process after facet dislocation. If the facets are fractured, the reduction may occur with lower weights, and good alignment will be achieved easily. Otherwise, if the facets are locked, too many weights are necessary, a reduction may be severe. Moreover, if the dislocation is delayed, closed reduction is almost impossible.

Secondly, there is still some controversy as to whether or not anesthesia is performed during traction-reduction. The observations of Evans [3] and Kleyn [7] popularized reduction under anesthesia, although other authors condemned the procedure as potentially dangerous compared with craniocervical tractionreduction. In 1994, a cohort study performed by Lee et al. [29] found a higher rate of success and a lower complication rate with traction-reduction as opposed to manipulation under anesthesia. In 1999, a prospective observational study by Vaccaro et al. [21] assessed the safety of awake closed reduction maneuvers in 11 patients with cervical spine dislocations. The results showed that none of the patients in their study suffered from neurological worsening during or after closed reduction. Suitably, Vaccaro et al. [21] stated in the conclusion of the article that the implications related to the ŌĆ£neurologic safety of awake closed reduction traction reduction remains unclear.ŌĆØ However, there were also many authors who believed that manipulation under anesthesia was still a frequently practiced technique, usually used after failure of traction-reduction but occasionally used as a primary means of achieving reduction [11,30,31].

Thirdly, the need for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before reduction is a matter of debate. Some investigators believed that disc disruption in association with facet fracture-dislocation increases the risk of spinal cord injury by disc material after reduction [2,8,29,32]. Rizzolo et al. [33] found evidence of disc disruption/herniation in 42% of patients studied with prereduction MRI. Darsaut et al. [34] recommended MRI-guided reduction due to their observation of an incidence of 88% cervical disc disruption before closed reduction. Hart et al. [35] also believed that prereduction MRI was crucial, basing his argument on the supreme cost incurred if the diagnosis was missed even rarely. So, they recommend the use of prereduction MRI to assess for ventral cord compromise caused by traumatic disc disruption. On the other hand, some authors have found no relationship between findings on prereduction MRI, neurological outcome, or findings on postreduction MRI [5]. et al. [21] based his opinion that MRI was unnecessary in many cases on extensive clinical experience and prospective clinical data. A basic animal research has demonstrated that a relatively brief window of 1 to 3 hours is available, after which injury to the spinal cord caused by mechanical compression may become irreversible [36]. The use of prereduction MRI may delay reduction of the spinal deformity and therefore may delay decompression of the compromised spinal cord. Moreover, prereduction MRI assessment requires the transport of a patient with a highly unstable cervical spine fracture to the MRI suite. Many laboratories work also suggested that early reduction of fracture-dislocation injuries may improve neurological outcome [3,11,32,37].

In previous reports, the success rate of closed reduction ranged from 30% to 100% [9,18,20,38] (Table 1). Those who failed closed traction reduction should perform open reduction as soon as possible. Many papers reported that closed reduction attempts could not be successful in all cases [39]. Some surgeons suggested that closed reduction was only suitable for conscious and cooperative patients, and for severely injured uncooperative patients, rapid open surgical reduction should be selected [40,41]. Besides, even after a closed reduction, open surgery with stabilization of the dislocated level is necessary. Since closed reduction requires close neurologic monitoring, imaging to monitor progress is not always feasible [42]. Some surgeons prefer to make an open reduction and stabilization surgery at the same sitting for those reasons. Lambiris et al. [43] believed that all patients with lower cervical facet dislocations had cervical spine instability due to soft tissue injury of the dislocated segment. Open surgery should be used to quickly stabilize the cervical spine, so that patients could exercise as soon as possible, which was beneficial to recovery. The cervical spine function could also avoid long-term external fixation and related complications. Dvorak et al. [44] conducted a controlled study of 90 patients and concluded that patients with open surgery had a better prognosis than patients with nonsurgical treatment. It was recommended that all patients should undergo open surgery after cranial traction. In summary, there is still a controversy about performing a closed reduction compared with open surgical reduction and fixation [39].

The surgical treatment of patients with lower cervical facet dislocation is indicated to improve neurologic deficit, to restore spinal mechanics through correction of a deformity, to stabilize unstable lesions, and to facilitate the patientŌĆÖs comfort [43,45]. There are many ways of surgical reduction, including anterior approach, posterior approach, and combined anterior-posterior approach. The choice of surgical way depends on many factors, including the patientŌĆÖs neurological status, whether it is combined with traumatic disc herniation, the success of closed reduction, unilateral or bilateral facet dislocation, whether there is a vertebral fracture or accessory fracture, and the surgeonŌĆÖs experience and habits [46].

Anterior-only approach surgery is mainly suitable for patients with structural injuries on the ventral side of the spinal cord, especially for the patients with traumatic disc herniation. Anterior-alone approach is surgically less traumatic owing to its blunt interplane dissections. Infection rate is lower compared with the posterior approach (0.1% to 1.6% vs. 16%) [47]. Direct access to the injured intervertebral disc enables decompression via discectomy.

Anterior stand-alone interbody bone grafting and fusion of lower cervical spine fracture dislocation was recognized and widespread following reports by Bailey and Badgley (1960), Cloward (1961), and Verbiest (1962). It was further refined by Bohler (1964), Orozco (1970), Tschern (1971), Senegal (1971), and Gassman and Seligson (1983) with the introduction of plate and screws to tackle earlier complications related to secondary deformity and graft extrusion [48]. In 1973, Cloward [49] reported a new surgical technique and instrument they called ŌĆ£cervical dislocation reducer,ŌĆØ which treated a patient with an unusual cervical dislocation successfully. de Oliveira [50] introduced that 12 patients with locked facets of lower cervical spine were surgically treated through an anterior approach using interbody disc spreaders in 1979. Since then, due to the unique advantages of anterior-only surgery, it has been widely popular, and the techniques and instruments have undergone continuous improvement [51-53].

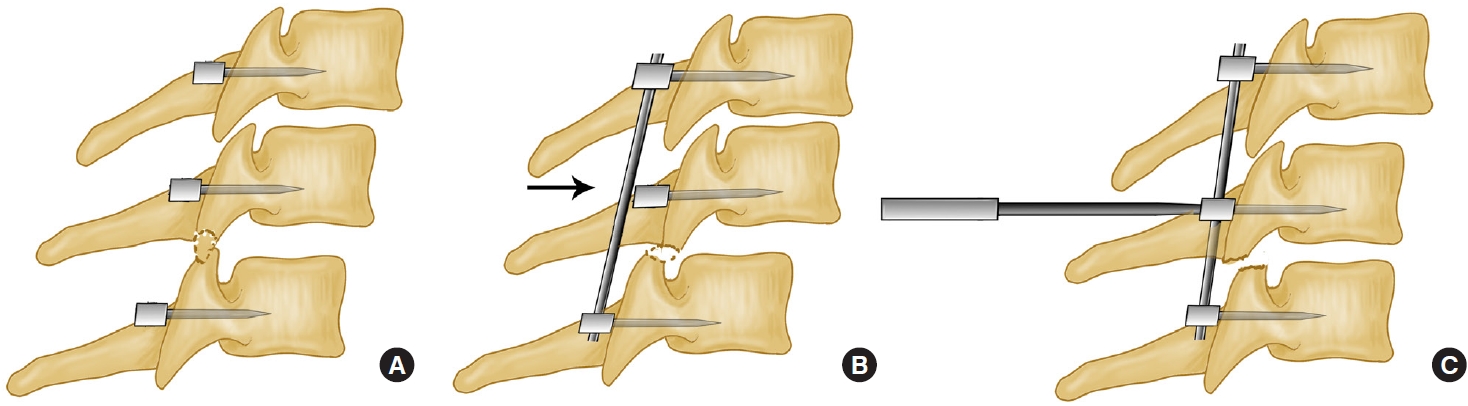

In 2000, Ordonez et al. [54] reviewed the previous experience and introduced the reduction techniques in detail with the anterior surgical approach in 10 patients with either unilateral or bilateral cervical facet dislocation. After a standard anterior approach discectomy to the cervical spine, vertebral body posts (Caspar or equivalent devices) were placed at approximately a 10┬░ to 20┬░ divergent angle with respect to each other. Angling the vertebral body posts provides for the application of a bending moment when distraction was applied. While the locked facets were disengaged, dorsally directed pressure to the rostral vertebral body into normal alignment could be applied using manual pressure or a curette (or similar device) (Fig. 3).

This technique was improved and supplemented in reports by Reindl et al. [27] in 2006 and Ren et al. [55] in 2020. There was still application of the Caspar retractor system with pins at the level above and below the subluxation or dislocated segments. The pins were placed in a convergent manner to apply a slight amount of kyphosis during the distraction maneuver. If this was not effective, a laminar spreader (Reindl) or a periosteal detacher (Ren) was inserted at the affected disc space. Distraction and cephalad rotation of the instrument were then used to unlock the dislocated facets (Fig. 4).

In 2014, Du et al. [56] reported that 17 patients monitored by spinal cord evoked potential were successfully reduced using a trial-model device as a lever. With spinal cord evoked potential monitoring, standard transverse incision was performed. After removal of disc and opening the posterior longitudinal ligament, anterior decompression of spinal cord was completed. Skull traction was maintained utile the inferior articular process of dislocated vertebrae was just right on top of the superior process of inferior vertebrae. Then they poked the inferior vertebrae to unlock the facet dislocation (Fig. 5).

Unfortunately, for some patients with delayed treatment or osteoporosis, the distraction force of conventional techniques may not be able to completely disengage the locked facets. In 2017, Zhang [57] reported the successful reduction of 4 patients with unilateral facet dislocation using the anterior pedicle distraction reduction technique who failed to use the vertebral distractor reduction technique. After anterior discectomy, a pedicle distractor (anterior screw tapper) was implanted from the anterior approach along the axis of the pedicle under fluoroscopy monitoring. The trial model used as a fulcrum was placed into the intervertebral, and the distractor could directly act the force on the locked facet. Then pressed down the spreader to pry and disengage the facet. When the inferior articular process of dislocated vertebrae was just right on top of the superior process of inferior vertebrae, the upper vertebrae was pushed in a caudad direction to achieve reduction (Fig. 6).

In 2017, Li et al. [58] believed that the conventional anterior approach techniques still had many disadvantages. Attention should be paid to intervertebral instrument insertion depth and the prevention of secondary spinal cord injury caused by instantaneous springing at the time of reduction. They reported a new anterior cervical distraction and screw elevating-pulling reduction technique. The 1st vertebral body superior of the involved segment and the 2nd vertebral body inferior thereto was drilled. After Caspar pins were driven into the drilled holes, Caspar vertebral body retractor was installed and used for longitudinal distraction until a certain tension of surrounding soft tissues was reached. An anterior cervical titanium plate with a length equal to the distance of distraction by the retractor was placed between 2 Caspar pins. Then a half-thread cancellous bone screw of appropriate size was driven into the middle of the plate to pull the dislocated vertebrae until it was pressed against the titanium plate (Fig. 7).

Moreover, Kanna et al. [47] also believed that the simultaneous application of traction and reduction maneuver using the same instrument (Caspar distracter or interbody spreader) did not allow un-locking of the facets. Repeated reduction attempts could be dangerous to the neural tissue and surrounding vascular structures. Hence, they introduced a modified anterior reduction technique used separate instruments in 2017, one for maneuvering the vertebral body and another for interbody distraction, to consecutively treat cervical facet dislocations. After identifying the subluxate segment, Caspar pins were placed on adjacent vertebral bodies parallel to the vertebral endplates in the craniocaudal plane and gently distracted under fluoroscopy monitoring. In the medio-lateral plane, it was essential to place the pins perpendicular to the plane of displacement in uni-facetal subluxation. Anterior cervical discectomy was performed ensuring complete decompression beyond the posterior longitudinal ligament and till the uncovertebral joints on either side. At this stage, the Caspar pin distracters were used for distraction, and an interbody spreader was placed between the vertebral bodies to sustain the distraction. And then the Caspar distracter was now removed leaving the Caspar pins in the vertebral body. The interbody spreader acted only as the distracter while the Caspar pins were used as ŌĆ£joy sticks.ŌĆØ The pins were moved to provide a transverse rotation or flexion-extension moment, depending on the side of facet subluxation (Fig. 8).

Even if the reduction techniques all above failed, Liu and Zhang [59,60] also proposed a novel anterior-only surgical procedure including kyphotic paramedian distraction with Caspar pins and anterior facetectomy in 2019. The successful rate of reduction was reported to be 100%. Kyphotic Paramedian Distraction with Caspar Pins: The level of the injured cervical spine was exposed through a standard Smith-Robinson approach. Two Caspar pins were placed at approximately a 10┬░ to 20┬░ with respect to each other in the sagittal plane. But the entry point and direction of the upper pin should be biased toward the dislocation side to provide greater distraction forces on the dislocated joint. Thus, the distraction was presented in a kyphotic paramedian manner, which mimicked segmental flexion to help facet subluxation (Fig. 9). This technique could reduce most lower cervical facet dislocations. Anterior facetectomy: This procedure was applicated after the failure of the kyphotic paramedian distraction technique. Anteromedial foraminotomy was performed by resection of posterior foraminal portion of the uncovertebral joint. After the nerve root was retracted in a cephalad direction in the neuroforamina, the edge of the dislocated superior facet was broken to achieve reduction. The Caspar retractor was pushed in a posterior direction to achieve posterior translation of upper segment and the broken lower segment (a part of the superior facet) (Fig. 10).

Although anterior-only approach surgery has many advantages [41] (Table 2), for some patients with delayed dislocations, it is difficult to open the facet joints directly with anterior-only approach techniques. In order to release the facet joints, the weight of traction is often given too much to them, which may cause secondary iatrogenic injury to the spinal cord. Especially, for patients with severe vertebral fractures or osteoporosis, they cannot even withstand the force of distracting provided by the spreader. Johnson et al. [61] described a 13% radiographic failure rate for anterior plate fixation in patients with flexion injuries of the subaxial cervical spine in 2004. They postulated that facet fractures might have an impact on the stability of anterior plate fixation. Amorosa and Vaccaro [62] also recommended that for patients with severe posterior column injury, the stability was not good enough after anterior surgery alone, which needed to add posterior fixation. Alternatively, the anterior pedicle screw and plate fixation reported by Zhang et al. [63] can also be used, so that the anterior-only approach can also meet the stability of the 3 columns (Fig. 11). However, this surgical technique is challenging and requires a highly experienced surgical team.

Posterior surgery is advocated because of its ease of reduction and restoration of the cervical spine alignment. After cervical spine trauma, the biomechanical advantages of posterior fixation and the high stability of cervical pedicle screw fixation have been reported. Especially for patients with posterior column damage, posterior reduction and fixation can provide higher stability than anterior approach [64-66]. For patients with old facet dislocation, severe vertebral fractures, osteoporosis, ankylosing spondylitis, or comminuted fractures of the facet joint, it may fail to reduction using anterior-only approach techniques. Therefore, some authors recommend performing posterior surgery directly or adding posterior fixation after anterior surgery [61,67,68].

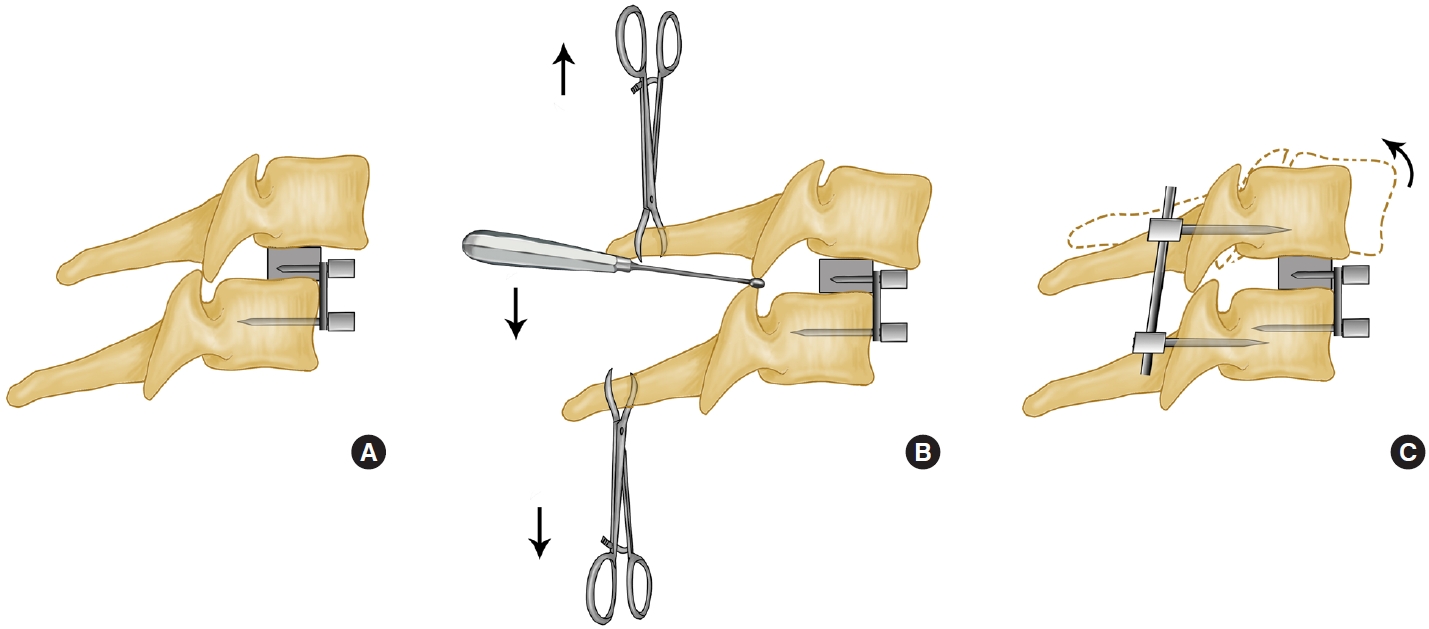

Historically, posterior open reduction was performed most frequently, and the technique consisted of instrument-assisted manipulation, a partial or complete facetectomy, reduction of deformity and dorsal fixation, and fusion. Fusion and instrumentation techniques included facet wiring, interspinous wiring, and placement of a lateral mass plate or pedicle screw rod system [6,69-78]. Especially for the reduction techniques with instrument-assisted manipulation, there were various instruments, including periosteal elevator, spinal curette, bone-holding forceps, pedicle screws and so on. In 1967, Alexander et al. [69] firstly reported the reduction technique assisted by a small sharp periosteal elevator (Adson). In the state of skeletal traction with Crutchfield tongs, a small sharp periosteal elevator was inserted between the facets, and gradually turned and twisted it until the separation between the two becomes wider and adhesions have been broken up. In some instances, if the adhesions could not be broken up, the ventral margin of the involved superior facet, or even the whole facet, might have to be removed to complete the reduction. Subsequently, using the same principle of leverage, Bunyaratavej et al. [79] in 2011 and Park et al. [80] in 2015 respectively reported a similar mean assisted by the spinal curette. A small straight spinal curette was placed between the inferior facet of the rostral vertebra and the superior facet of the caudal vertebra. With gentle pressure and a twisting maneuver, the curette tip would slide between them. The curette was then turned so that the cup side docked with the inferior edge of the rostral facet. Care must be taken not to place the tip of the curette more deeply than the inferior edge of the rostral facet to avoid injuring the exiting nerve root, which was located near the inferior edge of the rostral facet. The handle of the curette was then gently pulled caudally so that the rostral facet is levered up and over the caudal facet (Fig. 12).

Some authors who considered that some patients of cervical facet dislocation might combine with traumatic disc herniation, proposed that neurological damage would occur if we reduced the injured spine without adequate distraction force [81]. In 2001, Fazl and Pirouzmand [82] described a new technique for dorsal reduction of facet dislocations by use of a modified interlaminar spreader. As the same principle, Nakashima et al. [81] reported the use of bone-holding forceps for posterior reduction in the treatment of 40 patients with cervical fracture-dislocations and traumatic disc herniation in 2010. Firstly, axial traction was gently applied to the injured cervical spine using the Mayfield head holder before operation. After exposure, in cases of dislocation or subluxation, a distraction force was gradually applied between the spinous processes, using bone-holding forceps, to reduce anterior translation of the proximal vertebra. When the inferior articular process of dislocated vertebrae was just right on top of the superior process of inferior vertebrae, a dorsal force was pulled to the rostral vertebra to achieve reduction (Fig. 13).

If reduction could not be achieved, especially for old cervical subluxation, a high-speed burr might be used to release the locked facets by resection of the tip of the superior articular process of the distal segment. In 2014, Barrenechea [83] reported a 1-stage posterior technique utilized in the reduction of high-grade lumbar spondylolisthesis to reduce an old cervical subluxation. Under neurophysiologic monitoring, the patient was placed in a Mayfield head holder with her neck slightly extended. After opening and exposing the posterior elements, the locked C5ŌĆō6 facets appeared ossified. they performed a wide bilateral foraminotomy using a high-speed drill to refracture the partially ossified facets. And then, they placed 6 lateral mass screws (2 on C4, 2 on C5, and 2 on C6) followed by securing a rod from C4 to C6, spanning the C5 lateral mass screw. Resembling the technique utilized in the reduction of high-grade lumbar spondylolisthesis with ŌĆ£reduction screws,ŌĆØ they used a rod reducer to bring the C5 screw head back toward the rod, thus realigning the lateral mass screw heads and reducing the subluxation (Fig. 14).

Compared with anterior techniques, posterior techniques can directly release the locked facets, which is easier to reduce, and can also remove the compression on the dorsal side of the spinal cord (Table 3). Moreover, posterior pedicle screw fixation has better biomechanical stability which can provide more favorable conditions for long-term bone graft fusion [84,85]. However, the posterior-only surgery has its serious drawbacks: (1) The herniated intervertebral disc and other soft tissues on the ventral side of the spinal cord cannot be removed before reduction; (2) During the reduction of the posterior approach, the compressive materials may enter the spinal canal and compress the spinal cord, which bring iatrogenic surgical complications; (3) Patients with intervertebral disc destruction may be at risk of poor fusion rate and internal fixation failure due to lack of support for the anterior-middle column. Thus, a further anterior procedure should be considered in cases with canal compromise with traumatic intervertebral disc herniation [86].

Combined anterior and posterior fixation/fusion is the most definitive operation to maintain cervical stability after a fracture or dislocation, and this has been demonstrated by many authors in biomechanical experiments or clinical studies. Therefore, it has been more recommended for the treatment of a bilateral dislocation than anterior or posterior fixation/fusion alone, which are more accepted in unilateral dislocation [87-89].

Because of reduction via the posterior approach is less challenging than that via the anterior approach, almost all the reduction techniques used by the authors are from the posterior approach mentioned before, and the only difference is the sequence of the surgical approach. There are many ways of combined approach surgery, including anterior-posterior, posterior-anterior, anterior-posterior-anterior, and posterior-anterior-posterior approaches. In 2008, Liu et al. [90] reported a novel operative approach for the treatment of old distractive flexion injuries of subaxial cervical spine. They firstly performed facetectomy and released sufficient soft tissue for reduction, fixed with spinous process wire, and used morselized autogenous cancellous graft harvested from the posterior iliac process to posterior element fusion through a posterior approach. And then an anterior approach surgery was performed for decompression, fusion and internal fixation. Thereafter, there have been more authors who recommend posterior-anterior order used posterior lateral mass screws or pedicle screws for fixation [91,92]. In recent years, with the advancement of minimally invasive techniques in recent years, considering that traditional posterior surgical trauma will bring complications such as neck pain, some authors have used minimally invasive techniques to achieve posterior release and reduction. In 2019, Shimizu et al. [93] reported a fluoroscopy-assisted posterior percutaneous reduction technique for the management of unilateral cervical facet dislocations. The reduction instrument and principle were the same as those reported by Alexander et al. [69] in 1967, except that Shimizu et al. [93] inserted the elevator into the locked facet percutaneously through a small incision above the facet with fluoroscopic assistance, and reduction was achieved by lever action without complications. Subsequently, Yang et al. [94] reported 4 cases of old subaxial cervical facet dislocations unlocked by the posterior approach under endoscopy followed by anterior decompression, reduction, and fixation.

However, cases have been reported of patients who were neurologically intact before intraoperative reduction, but who experienced a deficit after the reduction [30,95]. Some authors recommend anterior discectomy first, and if the reduction can be obtained by means of the anterior incision, the anterior column can be grafted and fused using standard techniques. If required, this procedure can be followed by posterior fusion and instrumentation. There have been many studies of anterior-posterior surgery in recent decades [96-99]. Feng et al. [100] described a surgical technique of anterior decompression and nonstructural bone grafting followed by posterior reduction and fixation in 2012. The patients were firstly placed in the supine position. After discectomy through a standard Smith-RobinsonŌĆÖs anterior cervical approach, the Caspar distraction pins were placed divergently in a rostrocaudal fashion and the disc space was distracted 1 to 3 mm to restore near-normal disc height and to correct the kyphosis. A layer of absorbable gelatin sponge was gently filled into one-third of the posterior disc space to protect the exposed spinal cord and prevent dislocation of cancellous bone graft. Afterwards, a layer of morselized cancellous bone grafts from the iliac crest was placed in two-thirds of the anterior disc space, restoring proper intervertebral height and lordosis. Then a layer of gelatin sponge was placed on the surface of bone graft, and the longus colli muscle was opposed over the sponge and stitched carefully. The anterior wound was closed and turn to prone position, and then the posterior reduction and internal fixation of the lateral mass screws were performed (Fig. 15).

On the other hand, if the reduction cannot be succeeded through the anterior approach, a posterior approach must be used to obtain the reduction, which leaves a question of how to address the anterior fusion and instrumentation. Often, after posterior reduction and fusion, the anterior column is approached again to place a bone graft in the disc space and affix a plate, requiring yet a third procedure to complete the treatment. This technique was rarely used in the past because of its complicated procedures and complications. Bartels and Donk [101] reported the anterior-posterior-anterior approach and posterior-anterior-posterior approach for the treatment of delayed traumatic bilateral cervical facet dislocation in 2002.

In order to avoid the third procedure, some authors applicated some new means of anterior bone grafting. In 2001, Allred and Sledge [102] described a technique for grafting and instrumentation of the anterior cervical spine before reduction using tricortical iliac crest bone graft secured with a buttress plate. In 2013, Song et al. [103] considered that the buttress plate did not provide safety from graft motion or impingement of the spinal cord since it did not completely fix the interbody graft. Therefore, they reported a modified technique using a prefixed polyetheretherketone cage and plate system. Similarly, Wang et al. [104] reported a novel surgical approach, which was successfully applied to treat 8 cervical facet dislocation patients. After anterior discectomy, a suitable peek frame cage, containing the autologous iliac bone particles or tricalcium phosphate bone substitute, was inserted in the position to fill the interspace. And then, by using 2 screws, an appropriate anterior peek composite buttress plate was added to fix the cage to the lower vertebral body. The anterior wound was closed, and the patient was placed carefully in the prone position for the posterior manipulation. Reduction of the facet dislocations was gradually achieved by gentle distraction of the involved spinous processes with tooth forceps and prying the locked facets with a reset handle, as well as positioning the patientŌĆÖs neck progressively into extension at the same time. Finally, posterior internal fixation was performed using mass screws or pedicle screws (Fig. 16).

Combined approach surgery has the both advantages of anterior-only approach and posterior-only approach (Table 4). However, the sequence of combined approach is still controversial. The sequences and techniques of surgical decompression and fixation need to be determined according to the specific conditions of the patient. The procedure is more complicated than anterior-only or posterior-only approach, which requires a higher physical condition of patient and results in a higher risk of postoperative infection. Furthermore, multiple changes of position may even cause secondary spinal cord injury.

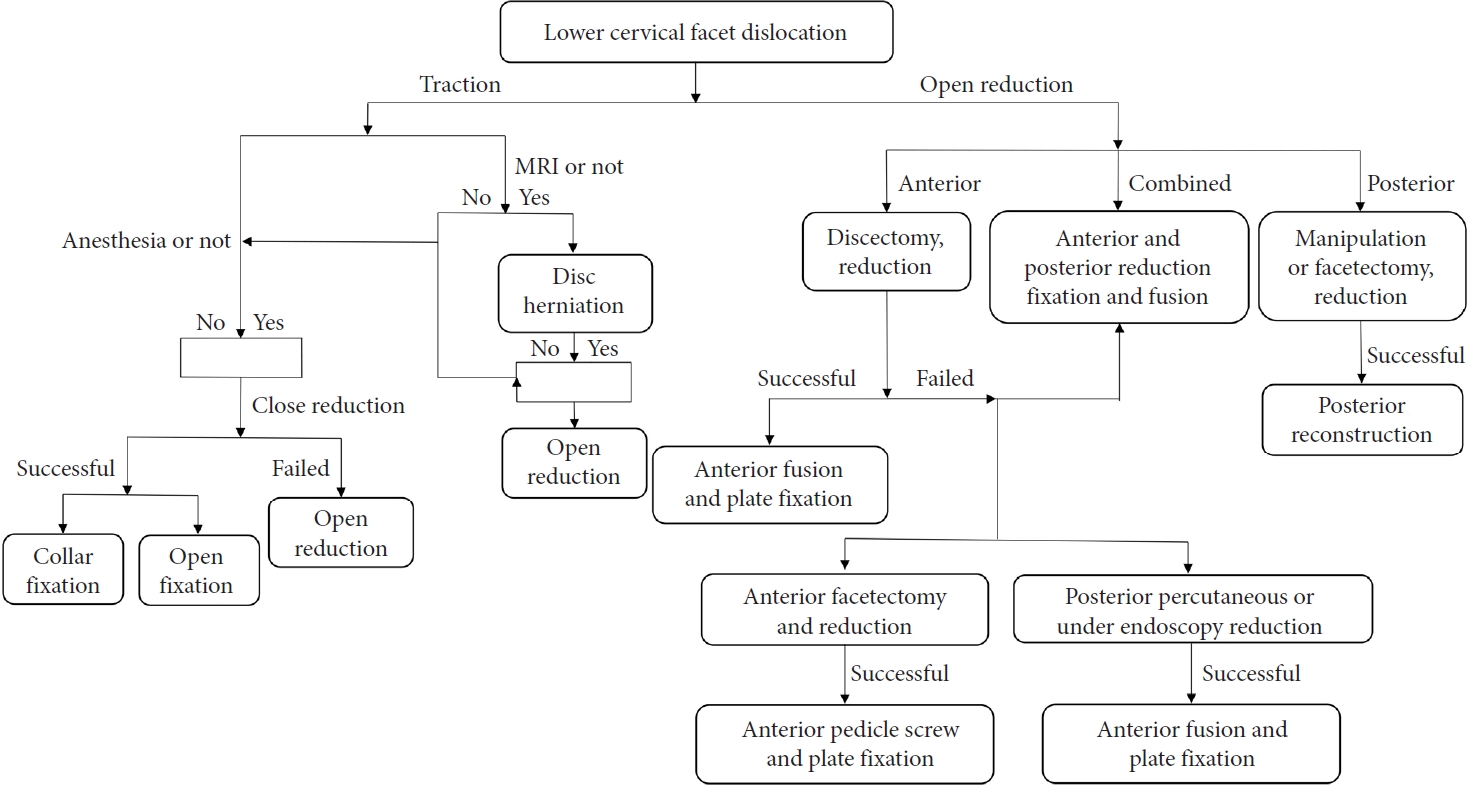

Although there were many treatment strategies and algorithms in the past [42,105,106], the optimum treatment strategy and algorithm of cervical facet dislocation is still a matter of debate (Fig. 17). Despite agreement in the literature over the role of closed reduction and surgical treatment of these injuries, there are still areas of debate including indications for MRI and MRI timing. The selection of surgical approach depends on a combination of factors, including surgeon preference, patient factors, injury morphology, and inherent advantages and disadvantages of any given approach [42,107].

NOTES

Fig.┬Ā1.

Imaging studies of the illustrative case with C5ŌĆō6 bilateral facet dislocation. Preoperative lateral radiograph (A), and sagittal computed tomography (CT) (B) showing a C5ŌĆō6 dislocation and vertebral translation (arrows). (C) T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging showing C5ŌĆō6 intervertebral disc herniation (arrow) and spinal cord compression. (D-F) Sagittal CT and 3-dimensional reconstruction of the patient showing C5ŌĆō6 bilateral facet dislocation (arrows).

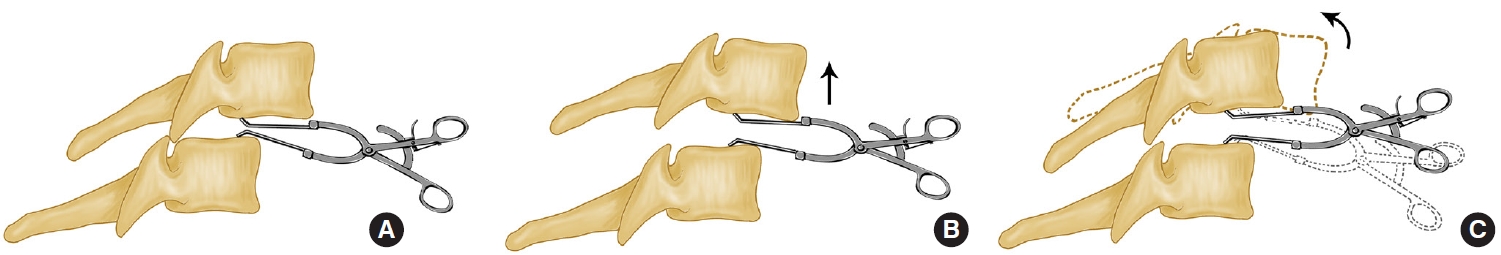

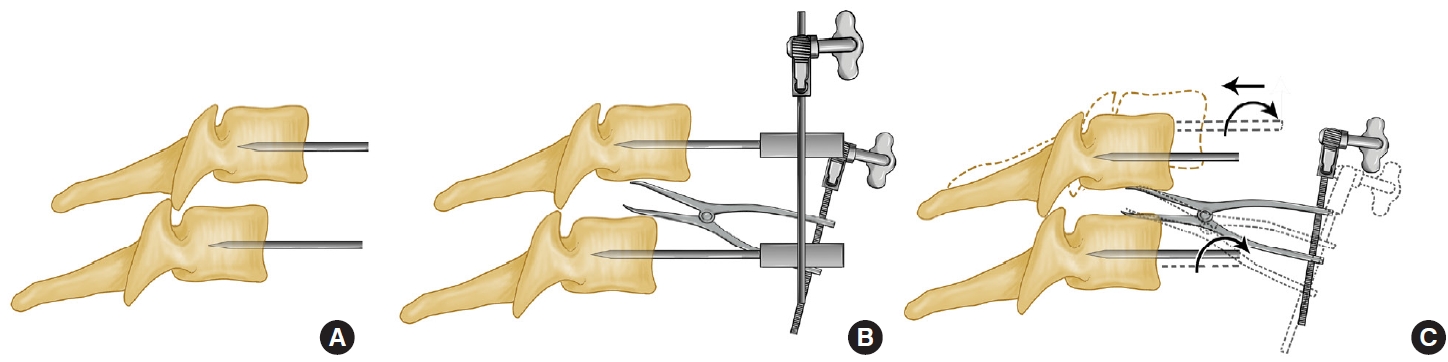

Fig.┬Ā2.

Illustrations of closed reduction. (A) Lateral image of facet dislocation. (B) The weight of in-line traction is increased gradually under fluoroscopy monitoring, until the articular process is completely unlocked. (C) While maintaining the traction, manually push the upper vertebrae in a caudad direction to achieve reduction.

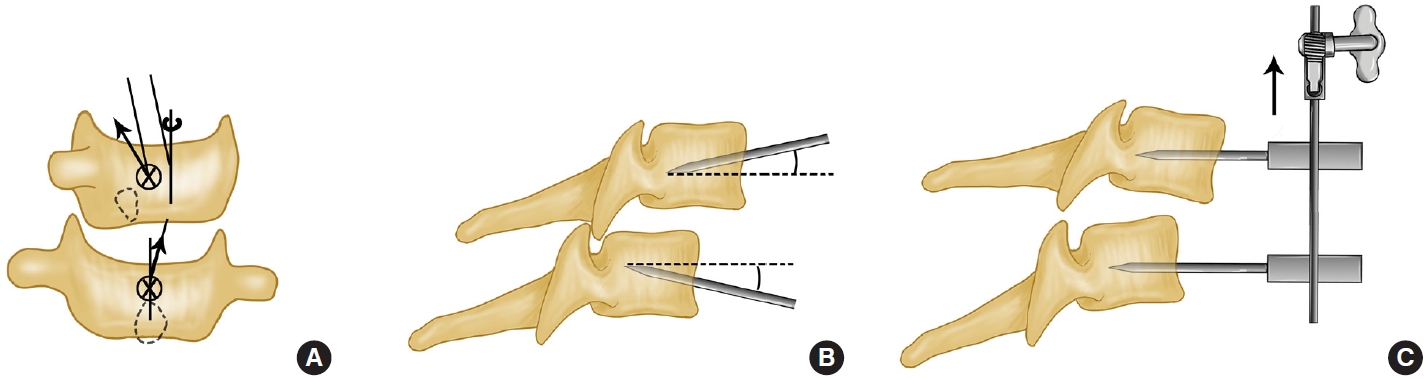

Fig.┬Ā3.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of the Caspar pins or the intervertebral distractor. (A) Placing Caspar pins at approximately a 10┬░ to 20┬░ with respect to each other in the sagittal plane. (B) permitting the creation of a kyphosis utile the inferior articular process of dislocated vertebrae was just right on top of the superior process of inferior vertebrae, which in turn disengages the facets. (C) An assistance of dorsal force is applicated to the rostral vertebra. (D) A disc interspace spreader is used to reduce deformities by placing the spreader in the disc interspace at an angle. (E) Distraction to disengage the facet joints. (F) Rotation to reduce the deformity (dotted vertebra) is then performed.

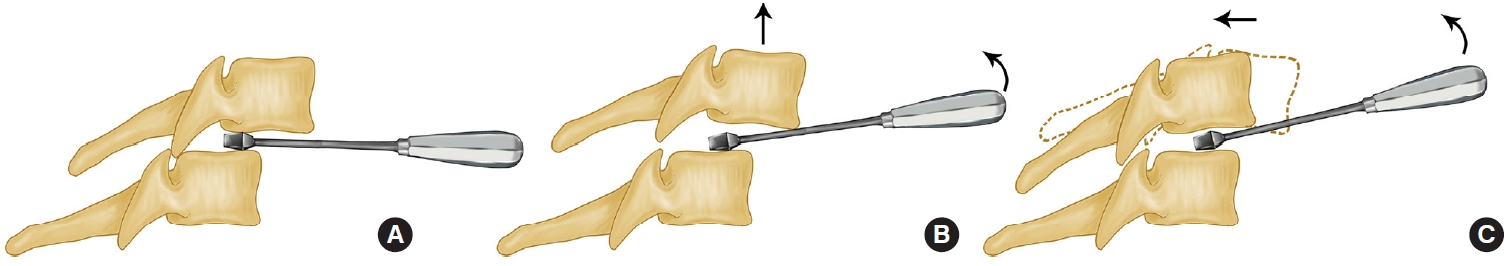

Fig.┬Ā4.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of the laminar spreader. (A) Insertion of the laminar spreader which is inserted as far posteriorly as possible but not beyond the posterior wall of the upper vertebra into the cleared disc space. (B) Following by gradual distraction of the disc space under fluoroscopic guidance. (C) Once the facet joints are cleared, the spreader is pushed in a caudad direction to achieve posterior translation of the upper segment.

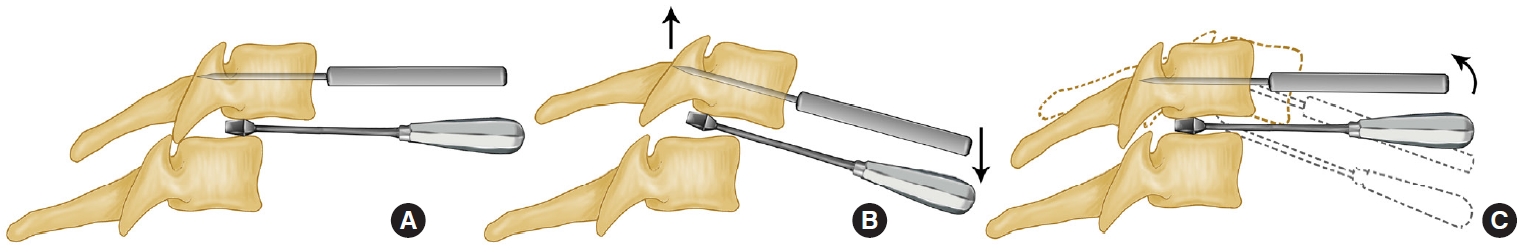

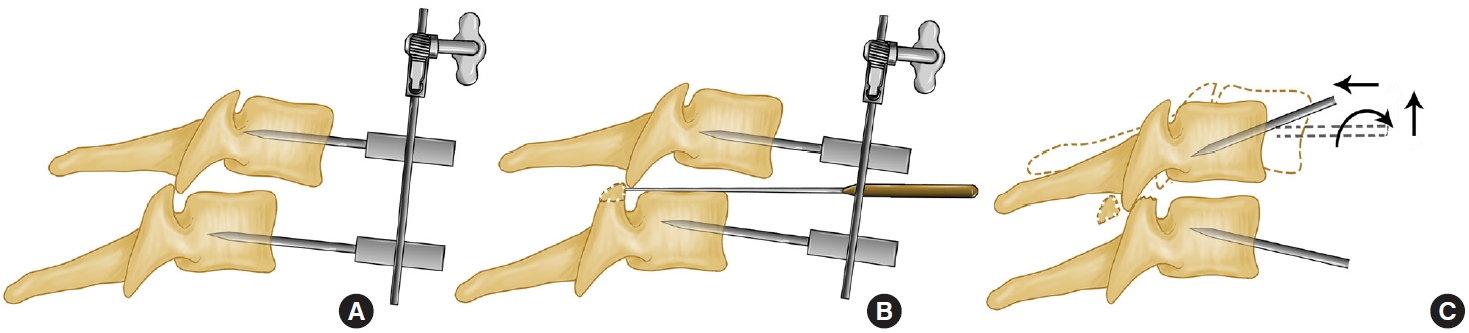

Fig.┬Ā5.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of the trial-model device. (A) Insert the trial-model device after removal of the involved intervertebral disc. (B) The weight of traction is increased gradually utile the inferior articular process of dislocated vertebrae was just right on top of the superior process of inferior vertebrae. (C) Poke the inferior vertebrae to unlock the facet dislocation (reduction by leverage).

Fig.┬Ā6.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of anterior pedicle distractor. (A) After anterior discectomy, a pedicle distractor (anterior screw tapper) is implanted from the anterior approach along the axis of the pedicle under fluoroscopy monitoring. The trial model used as a fulcrum is placed into the intervertebral as far posteriorly as possible but not beyond the posterior wall of the upper vertebra. (B) Press down the spreader to pry and disengage the facet. (C) Push the upper vertebrae in a caudad direction to achieve reduction, when the inferior articular process of dislocated vertebrae was just right on top of the superior process of inferior vertebrae.

Fig.┬Ā7.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of screw elevating-pulling. (A) Drill the holes of the Caspar vertebral body retractor to be installed in the 1st superior and the 2nd inferior vertebrae body of the involved segment. (B) Under intraoperative fluoroscopic monitoring, gradually distract until the facet joints are cleared. An anterior cervical titanium plate with a length equal to the distance of distraction by the retractor was placed between 2 Caspar pins, and then implant a suitable length of half-thread cancellous bone screw into the middle vertebral body. (C) Pull the dislocated vertebrae until it was pressed against the titanium plate.

Fig.┬Ā8.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of the separate instruments. (A) Placement of Caspar pins parallel to the endplates in the sagittal plane and perpendicular to the vertebral body in the axial plane. (B) The Caspar pin distracters are used for distraction, and an interbody spreader is placed between the vertebral bodies to sustain the distraction. (C) The Caspar distracter is removed leaving the Caspar pins in the vertebral body. The interbody spreader act as a distracter while the Caspar pins are used as ŌĆ£joy sticks.ŌĆØ The pins are moved to provide a transverse rotation or flexion-extension moment to reduce.

Fig.┬Ā9.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of kyphotic paramedian distraction with Caspar pins. (A) Direction of the upper pin place at the dislocation side in the axial plane. (B) Placing Caspar pins at approximately a 10┬░ to 20┬░ with respect to each other in the sagittal plane. (C) After anterior discectomy, gradual distraction (arrow) under fluoroscopy until disengagement of locked facets was observed on the lateral view. Application of dorsal and rotational force to the rostral vertebra to achieve reduction.

Fig.┬Ā10.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of anterior facetectomy. (A) Facet locking remains after the kyphotic paramedian distraction. (B) An anteromedial foraminotomy by resection of the posterior foraminal area of uncovertebral joint. Resection of the edge of the dislocated superior facet after the nerve root was retracted cephalad in the neuroforamina. (C) Application of the dorsal and rotational force (arrow) to the rostral vertebra to achieve reduction.

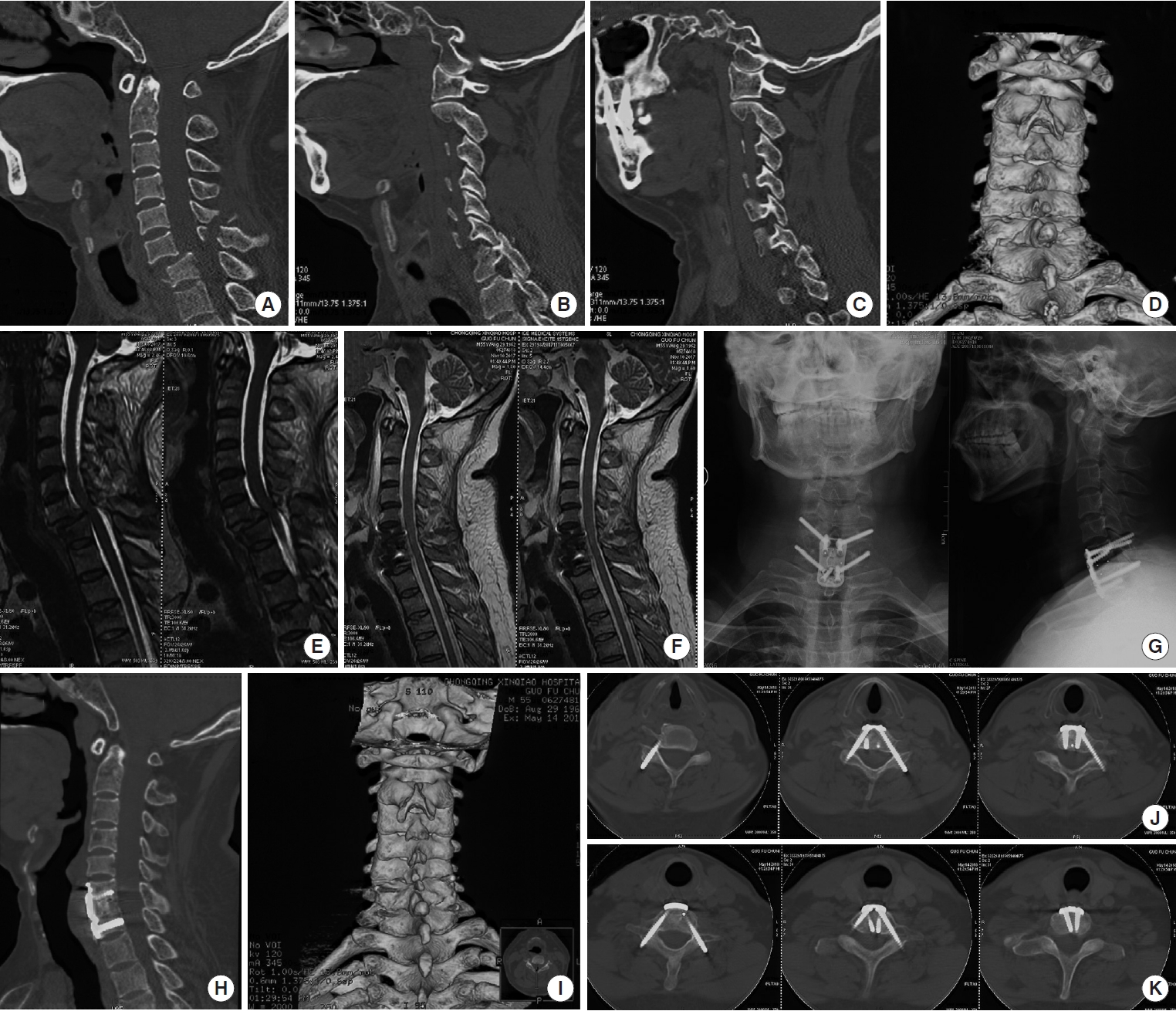

Fig.┬Ā11.

Preoperative and postoperative imaging studies of the illustrative case of C6/C7 bilateral dislocation. (A-D) Preoperative computed tomography (CT) images showing the C6/C7 right (B) and left (C) facet joint dislocation. (E-F) Preoperative (E) and postoperative (F) T2 sagittal magnetic resonance images showing C6/C7 spinal cord compression and decompression. (G) Postoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiograph showing the reduction and fixation of anterior pedicle screws and plate. (H) Six monthsŌĆÖ postoperative sagittal CT images showing C6/C7 fusion and sagittal alignment. (I) Six monthsŌĆÖ postoperative 3-dimensional CT reconstruction image showing right facet fusion after facetectomy. (J-K) Postoperative axial CT images demonstrating good placement of anterior pedicle screws and vertebra screws at C6 (J) and C7 (K). Reprinted from Liu and Zhang. World Neurosurg 2019;128:e362-9, with permission of Elsevier, Inc [59].

Fig.┬Ā12.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of spinal curette. (A) A curette is placed between the locked facets and the curette is turned so that the cup side docks with the inferior edge of the facet. (B) The curette is gently pull caudally so that the inferior facet is levered up and over the superior facet. (C) Application of dorsal and rotational force to the rostral vertebra to achieve reduction.

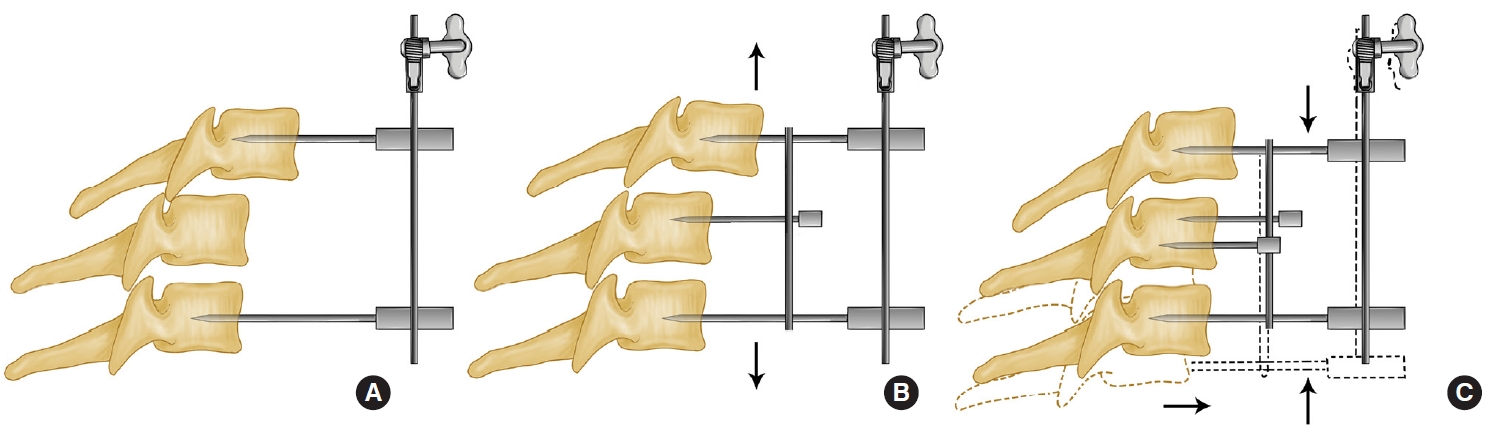

Fig.┬Ā13.

Illustrations of the reduction principle of bone-holding forceps. (A) Two bone-holding forceps were fixed between the spinous processes of the 2 dislocated vertebrae. (B) A distraction force was gradually applied between the spinous processes, using bone-holding forceps, utile the inferior articular process of dislocated vertebrae was just right on top of the superior process of inferior vertebrae. (C) Application of a dorsal force to the rostral vertebra to achieve reduction.

Fig.┬Ā14.

Illustrations of the principle of lifting reduction. (A) Perform a wide bilateral foraminotomy using a high-speed drill to refracture the partially ossified facets and place 6 lateral mass screws. (B) Securing a rod across one side of the screws. (C) Use a rod reducer to bring the middle screw head back toward the rod, thus realign the lateral mass screw heads and reduce the subluxation.

Fig.┬Ā15.

Illustrations of the procedure of anterior decompression, nonstructural bone grafting and posterior fixation. (A) After anterior discectomy, the Caspar distraction pins were placed divergently in a rostrocaudal fashion, the disc space was distracted 1 to 3 mm to restore near-normal disc height and to correct the kyphosis and the cancellous bone grafts was placed. (B) After anterior bone grafting, posterior reduction was performed. (C) Finally, posterior fixation was performed to provide instant stability.

Fig.┬Ā16.

Illustrations of the procedure of the new cage and plate system. (A) The cage containing autologous iliac bone particles or tricalcium phosphate bone substitute placed in the interspace after discectomy and fixed anteriorly with a peek composite buttress plate. (B) Posterior reduction of the facet dislocations was gradually achieved by gentle distraction of the involved spinous processes with tooth forceps and prying the locked facets with a reset handle. (C) Posterior internal fixation was performed using mass screws or pedicle screws after reduction.

Fig.┬Ā17.

Synthesized diagrammatic flow chart depicting clinical heterogeneity within the treatments of lower cervical dislocation.

Table┬Ā1.

Summary of close reduction techniques for lower cervical facet dislocation

| Study | Cases description | Reduction technique | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evans [3] 1961 | 17 Patients treated by induction of anesthesia and intubation, sometimes with manipulation under anesthesia. | Fig. 2 | No neurological deterioration noted. | Reduction under anesthesia safe and effective. |

| All (100%) successfully reduced. | ||||

| Pre-MRI. | 2 Unchanged, 2 died, 13 improved. | |||

| Burke and Berryman [4] 1971 | 41 Patients treated by MUA, light traction followed by induction of anesthesia and intubation, followed by manipulation under anesthesia if necessary. | Fig. 2 | 37 of 41(90.2%) successfully reduced by MUA. | MUA and traction both safe if proper diagnosis and careful attention paid to radiographs. |

| 32 patients treated with traction. | 21 of 25 (84%) reduced with traction alone before anesthetic. | |||

| 3 treated by traction after traction for stabilization, not reduced. | 7 Patients were judged too sick manipulation failed for anesthesia and underwent traction for stabilization, not reduced. | |||

| C7-T1 not attempted. | 2 Cases of neurological deterioration: 1 overdistraction and 1 unrecognized injury. | |||

| Shrosbree [5] 1979 | 216 Patients treated by manual traction, tong traction, and open Reduction. | Fig. 2 | 70 of 95 unilaterals reduced (74%), 77 of 121 bilaterals reduced (64%). | Traction followed by manipulation is safe and usually effective, and reduction seems to improve outcome. |

| Used traction (no weight specified) followed by manipulation under anesthesia if traction failed. | No neurological morbidity reported. | |||

| Pre-MRI. | Patients who were successfully reduced improved more often than patients who were not successfully reduced (41% vs. 32% unilateral, 16% vs. 0% bilateral). | |||

| Sonntag [6] 1981 | 15 patients of bilateral locked facets. | Fig. 2 | 10 of 15(66.7%) successfully reduced by traction: 6 were reduced with manual manipulation (traction, flexion), 4 were reduced with progressive weight application with administration of sedatives and muscle relaxants. | Stepwise algorithm (traction, manual manipulation, operative reduction) is indicated. |

| Retrospective series. | ||||

| Weight used ranged from 25 (11.3 kg) to 75 lb (34 kg). | Closed reduction by weight application is the preferred method for reduction of deformity. | |||

| No MRI done. | ||||

| Kleyn [7] 1984 | 101 patients treated by traction. | Fig. 2 | 82 of 101 successfully reduced (4 open reduction, 6 partial reduction accepted, 9 no further attempt owing to poor condition of patient). | Traction followed by MUA is safe, usually (80%) effective, and may result in improved neurological function. |

| Unilateral and bilateral, all with neurological involvement. | 37 of 45 incomplete lesions improved, | |||

| If injury < 24 hr, MUA attempted initially; if reduction fails with maximum of 18-kg weight, MUA performed. | 7 of 56 complete lesions improved. | |||

| No neurological deterioration. | ||||

| Maiman et al., [8] 1986 | 28 Patients. | Fig. 2 | 10 of 18 reduced with traction. | Mixed group of patients and treatments. In general, traction seemed to be safe. |

| Variety of treatments offered. | No patient treated by authors deteriorated. | |||

| 18 Patients had attempt at closed reduction (maximum weight, 50 lb [22.7 kg]). | 1 Referred patient had an overdistraction injury. | |||

| No MRI done. | ||||

| Sabiston et al., [9] 1988 | 39 patients (Retrospective series). | Fig. 2 | 35 of 39 patients (90%) successfully reduced. | Closed reduction with up to 70% of body weight is safe and effective for reducing locked facets. |

| Unilateral and bilateral. | No neurological deterioration. | |||

| All acute injuries. | Failures due to surgeon unwillingness to use more weight. | |||

| Up to 70% of body weight used. | ||||

| Star et al., [38] 1990 | 57 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 2 | 53 of 57 (93%) reduced. | Closed reduction is safe and effective for decompressing cord and establishing spinal alignment. |

| Unilateral and bilateral. | No patient deteriorated a Frankel grade. | |||

| Early rapid reduction attempted in all patients. | 2 Patients lost root function, 1 transiently. | |||

| No MRI done before reduction. | 45% Improved 1 Frankel grade by time of discharge, | |||

| 1 Patient was a delayed transfer weights up to 160 lb (72.6 kg) (began at 10 lb [4.5 kg]). | 23% improved less substantially. | |||

| 75% of patients required >50 lb (22.7 kg). | ||||

| Hadley et al., [77] 1992 | 68 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 2 | 58% of patients had successful reduction. | Early decompression by reduction led to improved outcomes based on fact that patients who did best were reduced early (5ŌĆō8 hr). |

| Facet fracture dislocations only. | Overall, most patients (78%) demonstrated neurological recovery by last follow-up (not quantified). | |||

| Unilateral and bilateral. | No comparison possible between closed reduction and ORIF because of small numbers. | |||

| 66 Treated with early attempted closed reduction (2 late referrals). | 7 patients deteriorated during ŌĆ£treatmentŌĆØ (6 improved following ORIF, 1 permanent root deficit following traction) | |||

| Average weights used for successful reduction were between 9 (4.1 kg) and 10 lb (4.5 kg) per cranial level. | 1.2% Permanent deficit (root) related to traction. | |||

| Mahale et al., [12] 1993 | 341 Patients treated for traumatic dislocations of cervical spine. | Fig. 2 | Complete injuries: 6 after OR, 1 after manipulation. | Numbers of patients subjected to each treatment arm not given. |

| 15 Suffered neurological deterioration. | Incomplete injuries: 1 after OR, 3 after manipulation, 2 after traction, 1 during application of cast. | Purely a descriptive article. | ||

| Variety of treatments used to reduce deformity (4.3%). | Radiculopathy: 1 (occurred when tongs slipped during traction). | Neurological deterioration can occur and the early use of MRI or CT myelography is recommended. | ||

| Deterioration delayed in 11 patients. | ||||

| Rizzolo et al., [13] 1994 | 24 Patients (all awake). | Fig. 2 | All 24 reduced. | Reduction with weights up to 140 lb is safe and effective in monitored setting with experienced physicians. |

| Prospective study. | No incidence of neurological deterioration. | |||

| No fractured facets. | Manipulation used in addition to weights in 9 patients (when facets perched). | |||

| All acute injuries. | ||||

| Weights up to 140 lb (63.5 kg) used. | Time required ranged from 8 to 187 min. | |||

| No CT or MRI done. | ||||

| Lee et al., [29] 1994 | 210 Patients. | Fig. 2 | Reduction successful: MUA, 66/91 (73%); RT, 105 of 119 (88%). | Traction superior to MUA. |

| Manipulation under anesthesia in 91. | Both rapid traction and the use of weights up to 150 lb (68 kg) are safe. | |||

| Rapid traction-reduction in 119. | All failures in RT group were due study to associated fractures or delayed referral. | |||

| Retrospective historical cohort. | ||||

| Groups similar except traction group had longer delay to treatment. | Time to reduction (RT), 21 min. | |||

| Weights up to 150 lb (68 kg) used. | No loss of Frankel grade in either group. | |||

| No MRI done before reduction | 6 MUA and 1 RT had deterioration on ASIA score. | |||

| Vital et al,, [18] 1998 | 168 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 2 | 43% Reduced by traction without anesthesia (time, 2 hr). | Authors promote their protocol as a safe and effective means for reduction and stabilization of fractures. |

| Unilateral and bilateral. | ||||

| Employed manipulation under general anesthesia in minority of cases. | 30% Reduced by manipulation under anesthesia. | |||

| Used relatively light weights (maximum, 8.8 lb [4 kg] plus 2.2 lb [1 kg]. per level for maximum of 40 lb [18.1 kg]). | 27% reduced intraoperatively. | |||

| All patients operated on immediately after reduction or after failure of reduction. | 5 Patients did not reduce (delayed referral, surgical error). | |||

| MRIs not done before reduction (although disks noted in 7 patients?) | Authors observed no cases of neurological deterioration. | |||

| Grant et al., [20] 1999 | 82 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 2 | Successful reduction in 97.6%. | Closed reduction is effective and safe despite high incidence of MRI-demonstrable disk injuries/herniations. |

| All closed C-spine injuries with malalignment included. | Average time to reduction, 2.1┬▒0.24 hr. | |||

| Unilateral and bilateral locked facets. | Overall, ASIA scores improved by 24 h following reduction. | |||

| Early rapid closed reduction attempted in all patients. | 1 Patient deteriorated 6 h after reduction (probable root lesion). | |||

| MRI scans obtained after reduction. | 46% had disk injury on MRI, 22% had herniation. | |||

| ASIA and Frankel grades determined on admission at 6 and 24 hr. | Disk injury on MRI correlated with cord edema on MRI. | |||

| Weight up to 80% of patientŌĆÖs body weight. | Successful reduction in 97.6%. | |||

| OŌĆÖConnor et al., [22] 2003 | 21 Patients (retrospective case series). | Fig. 2 | 11 of 21 patients reduced successfully. | Anterior translation correlates to neurological deficit. |

| 1 Patient with transient neurological deficit. | ||||

| Greg Anderson et al., [23] 2004 | 45 Patients (of 132), retrospective study to determine a statistical model to predict neurological outcomes. | Fig. 2 | 88% Successfully reduced with closed reduction. | Age and initial motor score predict neurological outcome. |

| No patient deteriorated neurologically. | Timing of reduction did not correlate to outcome. | |||

| Reindl et al., [27] 2006 | 41 Patients, retrospective case series of patients treated with anterior fusion for cervical dislocations. | Fig. 2 | 33 of 41 cases reduced successfully. | Closed reduction successful in most cases. |

| 1 Patient deteriorated during surgery but recovered at 1 year. | Anterior surgery sufficient for stabilization. | |||

| Darsaut et al., [34] 2006 | 17 Patients, prospective nonconsecutive series. | Fig. 2 | Reduction successful in 11 of 17. | Traction reduction achieves patients spinal cord decompression. |

| Reduction under MRI. | 10 of 11 reductions achieved spinal canal decompression. | |||

| Tumial├Īn et al, [24] 2009 | Case report. | Fig. 2 | Successful closed reduction of spondyloptosis of C7 on T1. | Traction reduction of spondyloptosis is safe. |

| MRI and CT done before reduction. | ||||

| Weights up to 60 lb [27.2 kg] used (began at 20 lb [9.1 kg]). | ||||

| Miao et al., [25] 2018 | 40 Patients (retrospective case series). | Fig. 2 | 38 of 40 patients completely reduced. | Stepwise algorithm (traction, manipulation, anterior approach operative) is indicated. |

| Without vertebral body fracture. | Surgery significantly improved neurological function in all patients. | |||

| MRI and CT done before reduction. | Closed reduction successful in most cases. | |||

| Weight ranged from 7ŌĆō15 kg (began at 5 kg). | Anterior approach surgery sufficient for decompression and stabilization. |

Table┬Ā2.

Summary of anterior reduction techniques for lower cervical facet dislocation

| Study | Cases description | Reduction technique | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cloward [49] 1973 | Case report. | Fig. 3 | Successful reduction of spondyloptosis of C7 on T1. | The author describes a method and an instrument for reduction of dislocated cervical vertebrae. |

| Before the operation, skull traction reduction failed. | ||||

| de Oliviera, [50] 1979 | 12 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 3 | All 12 (100%) reduced by using Harrington distractor. | Reduction of interlocking facets can be easily and safely achieved through an anterior approach if technical details are correctly. |

| Firstly, skull traction failed to obtain reduction. | No neurological deterioration occurred. | |||

| Unilateral and bilateral. | ||||

| Ordonez et al., [54] 2000 | 10 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 3 | 9 of 10 (90%) reduced by using Caspar pins and a curette or disc interspace spreader. | The ventral surgical procedure is safe and effective. |

| Unilateral and bilateral. | MRI provides an effective means by which to identify traumatic disc herniations, but not necessarily be predictive of the development of disc herniation during attempted closed or open dorsal reduction of cervical facet dislocations. | |||

| Ligamentous injury with minimum or no bone disruption. | 8 of 10 revealed satisfactory sagittal plane alignment: 1 residual unilateral perched; 1 dorsal elements splayed and slight focal angulated. | |||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | 4 No changed in neurological status and 6 improved. | |||

| Reindl et al., [27] 2006 | 41 Patients (retrospective case series). | Fig. 4 | 6 of 8 (75%) reduced by using Caspar pins and a laminar spreader. | The author supports a protocol based on anterior surgery. |

| Firstly, Gardner-Wells traction was used to obtain reduction. | 2 of 8 anterior open reductions failed requiring posterior surgery. | Closed reduction successful in most cases. | ||

| Both anterior and posterior structures disrupted. | 1 Patient deteriorated during surgery but recovered at 1 year. | It is proposed that facet dislocation associated with a pedicle fracture may be an indication for an initial posterior approach. | ||

| CT done before operation. | ||||

| Du et al., [56] 2014 | 17 Patients (retrospective case series). | Fig. 5 | All 17 (100%) reduced by using Intraoperative skull traction and a trialmodel device. | Anterior cervical surgery monitored by spinal cord evoked potential is effective and safe. |

| Unilateral and bilateral. | ||||

| Under spinal cord evoked potential monitor. | ||||

| Zhang et al., [60] 2016 | 8 Patients (retrospective case series). | Fig. 10 | All 8(100%) reduced by anterior facetectomy reduction. | Anterior facetectomy reduction represents a safe and efficacious option for the treatment of cervical facet dislocation. |

| Unilateral and bilateral; with or without facet fracture. | No neurological deterioration occurred. | |||

| Delayed management (7ŌĆō52 days). | ||||

| Failed in the conventional anterior reduction. | ||||

| Zhang [57] 2017 | 15 Patients (case series). | Fig. 6 | All 15 (100%) reduced: 5 with Gardner-Wells traction, 6 with vertebra spreader, 4 with anterior pedicle distraction. | Stepwise algorithm (closed reduction for patients without traumatic disc herniation, conventional anterior open reduction, anterior pedicle distraction) is indicated. |

| Unilateral. | ||||

| Delayed management (7ŌĆō18 days). | ||||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | No neurological deterioration occurred. | Anterior pedicle spreader reduction represents an efficacious option for the delayed treatment of unilateral cervical facet dislocation. | ||

| Li et al., [58] 2017 | 86 Patients (retrospective study). | Fig. 7 | All 86 (100%) reduced: 44 with conventional anterior cervical reduction, 42 with distraction and screw elevating-pulling reduction. | Anterior cervical distraction and screw elevating-pulling reduction is a safe and effective operation method for cervical spine fractures and dislocations. |

| Distraction-flexion injury with bilateral facet locking. | ||||

| No facet fracture. | ||||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | No neurological deterioration noted. | |||

| Kanna et al., [47] 2018 | 39 Patients with cervical type C injury. | Fig. 8 | All 39 (100%) reduced: 5 unchanged, 4 died, 30 Improved. | The modified anterior reduction technique is safe and effective for sub-axial cervical dislocation (AO type C injuries). |

| Retrospective series. | One facet was fractured in 17 and both in 5 patients. | |||

| Unilateral and bilateral. | ||||

| No attempts at pre-operative reduction. | 13 Patients had a traumatic disc prolapse. | |||

| Using inter-laminar distracter to distract while Caspar pins were used as ŌĆ£joysticksŌĆØ. | No neurological deterioration noted. | |||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | One patient had a partial loss of reduction | |||

| Liu and Zhang [59] 2019 | 63 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 9 | All 63 (100%) reduced: 52 with kyphotic paramedian distraction using Caspar pins, 11 with anterior facetectomy. | A novel anterior-only reduction procedure including kyphotic paramedian distraction with Caspar pins and anterior facetectomy is indicated. |

| Unilateral and bilateral. | ||||

| With or without traumatic disc herniation. | ||||

| With or without appurtenance fracture. | No neurological deterioration noted. | The procedure presents a 100% reduction rate, even for patients with severe vertebral fracture, articular process fracture and delayed management of bilateral facet dislocation. | ||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | ||||

| Ren et al., [55] 2020 | 102 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 4 | 99 of 102 (97.1%) reduced by using Caspar pins and a periosteal detacher. | The anterior reduction and fusion is effective and safe. |

| Unilateral dislocations without severe spinal cord injuries. | 3 of 102 patients needed additional posterior reduction. | |||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | No neurological deterioration noted. |

Table┬Ā3.

Summary of posterior reduction techniques for lower cervical facet dislocation

| Study | Cases description | Reduction technique | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander et al., [69] 1967 | Technique note. | Fig. 12 | The reduction is brought about by a small sharp periosteal elevator. | The sooner reduction is carried out after the injury, the easier it will probably be. |

| The operation is indicated only for failed reduction or successful reduction but unstable. | ||||

| Sonntag [6] 1981 | 15 Patients (retrospective series). | No specified | All 15 reduced: 6 with manual reduction, 4 with traction, 5(33.3%) with posterior surgery (no specific technique mentioned). | Stepwise algorithm (traction, manual manipulation, posterior reduction) is indicated. |

| Closed reduction is unsuccessful. | ||||

| Bilateral. | 2 of 5 by posterior operation had increasing neurological deficits. | |||

| Fazl and Pirouzmand [82] 2001 | 52 Patients (technique note). | Fig. 13 | All 52 (100%) reduced by using a modified interlaminar spreader. | This new technique provides a feasible and reliable approach to open reduction of cervical facet dislocations. |

| Unilateral and bilateral. | No neurological deterioration noted. | |||

| Nakashima et al., [81] 2010 | 40 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 13 | All 40 (100%) reduced by using boneholding forceps or high-speed burr. | A 2-step algorithm is proposed. However, the incidence of neurological deterioration after posterior open reduction was zero, even in cases with traumatic cervical disc herniation. |

| With traumatic disc herniation. | No neurological deterioration observed. | |||

| Axial traction was gently applied. | 25% of total cases and 75% of incomplete paralysis cases improved postoperatively by Ōēź 1 grade in the ASIA impairment scale. | |||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | ||||

| Bunyaratavej and Khaoroptham [79] 2011 | 5 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 12 | All 5 (100%) reduced by using small straight spinal curettes. | The reported technique is safe and effective. |

| Closed reduction is unsuccessful. | No neurological deterioration occurred. | The exiting root and vertebral artery may be at the risk of injury if the curette is placed too deeply during the reduction maneuver. | ||

| No anterior compression. | ||||

| Unilateral. | The presence of facet fracture, disk herniation or bone fragments in a neuroforamina are contraindications from this technique. | |||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | ||||

| Barrenechea [83] 2014 | Case report. | Fig. 14 | The patient was reduced by a posterior technique resembling used in the reduction of high-grade lumbar spondylolisthesis. | This technique could be added into the decision-making option for cases without disk herniation. |

| A 2-month standing C5/6 facet dislocation. | ||||

| Without traction. | ||||

| Park et al., [80] 2015 | 21 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 12 | All 21 (100%) reduced (7 with traumatic disc herniations) by using a Kocher clamp and a curet. | Posterior open reduction followed by pedicle screw fixation or posterolateral removal of herniated disc fragments is a good treatment option for cervical facet dislocations. |

| Closed reduction is not attempted. | ||||

| Unilateral and bilateral. | ||||

| With 3 lb (1.4 kg) or 5 lb (2.3 kg) of traction. | All patients improved neurologically. | |||

| MRI and CT done before operation. | Disc fragments were successfully removed from the 7 patients with herniated discs. |

Table┬Ā4.

Summary of combined reduction techniques for lower cervical facet dislocation

| Study | Cases description | Reduction technique | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cybulsky et al., [87] 1992 | 21 Patients (retrospective series). | No specified | All patients underwent a posterior wiring procedure with bone graft supplementation first. | Combined posterior and anterior fusion or anterior fusion with halo orthosis is required to render the 3-column-injured cervical spine stable. |

| Three-column cervical spine injuries. | Persistent postoperative instability was identified in each of the patients under review. | |||

| Allred and Sledge [102] 2001 | 4 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 16 | All 4 patients were treated by using bone graft from the iliac crest with an anterior cervical buttress plate, and subsequent posterior reduction and fusion. | The reported technique was used successfully in the treatment of patients with irreducible dislocations of the cervical spine. |

| Dislocation with a prolapsed disc. | No neurologic deterioration occurred. | |||

| Bartels and Donk [101] 2002 | 3 Patients (case report). | Fig. 15 | 2 Patients reduced by anterior-posterior-anterior procedure, and the other 1 reduced by posterior-anterior-posterior procedure. | For delayed (> 8 weeks) traumatic bilateral cervical facet dislocation, the authors propose the following surgical treatment algorithm: (1) complete release of the facets with no attempt at reduction; (2) anterior microdiscectomy with reduction and anterior plate fixation; and (3) posterior (lateral mass or pedicle) fixation. |

| Older (> 8 weeks) facet dislocation. | ||||

| Bilateral. | No complications occurred. | |||

| Wang et al., [96] 2003 | 3 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 2 | 2 Patients with unilateral dislocation reduced by taction, followed by anterior-posterior procedure for fixation and fusion. | The authors described the use of a minimally invasive approach by means of the tubular dilator retractor system to instrument and fuse the posterior cervical spine. |

| 2 Unilateral and 1 bilateral. | 1 Patient with bilateral dislocation reduced and fixed by posterior surgery. | |||

| No complications occurred. | ||||

| Payer [97] 2005 | 5 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 10 | All 5 reduced by immediate anterior open reduction and combined anteroposterior fixation/fusion. | Immediate open anterior reduction of bilateral cervical locked facets and combined antero-posterior fixation/fusion was safe and reliable. |

| Bilateral. | ||||

| Plain radiographs and CT done before operation. | No surgical complication occurred. | |||

| Liu et al., [90] 2008 | 9 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 12 | All 9 reduced by a novel posterior-anterior procedure. | Using the posterior-anterior procedures, anatomic reduction was successfully achieved for old distractive flexion injuries of subaxial cervical spine. |

| Old distractive flexion injuries. | Neck pain significantly remitted and neurologic function improved. | |||

| All patients maintained the anatomic reduction until fusion, except for one who lost partial reduction but achieved fusion ultimately. | ||||

| Schmidt-Rohlfing et al., [92] 2008 | Case report. | Fig. 12 | The patient was successfully reduced by posterior approach, and then followed by anterior bone graft and instrumentation. | The authors felt that three-column lesion at the cervicothoracic junction necessitated combined posterior-anterior stabilization. |

| Unilateral fracture-dislocation C7-T1. | ||||

| Involving all 3 columns. | No complications occurred. | |||

| Feng et al., [100] 2012 | 21 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 15 | All 21 reduced by an anterior-posterior procedure (anterior discectomy and nonstructural bone grafting, posterior reduction and fusion). | Anterior decompression and nonstructural bone grafting and posterior fixation provide a promising surgical option for treating cervical facet dislocation with traumatic disc herniation. |

| Accompanied by traumatic disc herniation. | ||||

| 13 Unilateral and 8 bilateral. | No instrument failure and no complications occurred. | |||

| Song et al., [103] 2013 | Case report. | Fig. 16 | The patient was successfully treated by using a prefixed polyetherether-ketone cage and plate system (an anterior-posterior procedure). | The author reported a prefixed polyetherether-ketone cage and plate system for the treatment of irreducible bilateral cervical facet fracturedislocation. |

| Bilateral. | ||||

| Fracture-dislocation with a prolapsed disc. | No instability or complications. | |||

| Wang et al., [104] 2014 | 8 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 16 | All 8 patient was successfully treated by using a new anterior-posterior procedure (after anterior discectomy, a peek frame cage composite buttress plate was used, and subsequent posterior reduction and fusion). | The reported surgical approach is an efficient and safe way for the treatment of traumatic cervical facet dislocations. |

| Bilateral and unilateral. | ||||

| With traumatic disc herniation. | ||||

| 4 Accompanied with facet fractures. | No neurological deterioration or instrument failure occurred. | |||

| Ding et al., [98] 2017 | 17 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 15 | All 9 reduced by an anterior-posterior procedure (anterior discectomy and morselized bone grafting, posterior reduction and fusion). | Anterior release and nonstructural bone grafting combined with posterior reduction and fixation provided a safe and effective option for treating old lower cervical dislocations. |

| Old facet dislocations. | ||||

| 10 Unilateral and 7 bilateral. | No neurologic deterioration and no procedure-related complications. | |||

| 8 With traumatic disc herniation. | ||||

| Miao et al., [99] 2018 | 24 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 2 | All 24 successfully treated by immediate reduction under general anesthesia and combined anterior and posterior fusion. | Immediate reduction under general anesthesia and combined anterior and posterior fusion can be used to successfully treat distraction-flexion injury in the lower cervical spine. |

| 16 Unilateral and 8 bilateral. | ||||

| Skull traction was performed with spinal cord evoked potential monitoring. | No major complications occurred. | |||

| Shimizu et al., [93] 2019 | Case report. | Fig. 12 | The patient was achieved posterior percutaneous reduction with an elevator. | This novel reduction technique, which contains posterior percutaneous approach and subsequent ACDF, could be a useful option for the management of cervical facet dislocations. |

| Unilateral cervical dislocation. | ||||

| Fluoroscopy-assisted | No complications or neurological deterioration observed. | |||

| Yang et al., [94] 2019 | 4 Patients (retrospective series). | Fig. 12 | All 5 reduced by using the procedure of posterior unlocking combined with anterior reduction. | For patients with old SCFD, the unlocking of facet joints via the posterior approach under endoscopy followed by anterior decompression, reduction, and fixation is an alternative technique. |

| Old subaxial cervical facet dislocations. | No neurological deterioration or iatrogenic injury occurred. | |||

| The neck visual analogue scale score and disability index were improved. |

REFERENCES

1. Walton GL. A new method of reducing dislocation of cervical vertebrae. J Nerv Ment Dis 1893;20:609.

2. Crutchfield WG. Skeletal traction in treatment of injuries to the cervical spine. J Am Med Assoc 1954;155:29-32.

4. Burke DC, Berryman D. The place of closed manipulation in the management of flexion-rotation dislocations of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1971;53:165-82.

5. Shrosbree RD. Neurological sequelae of reduction of fracture dislocations of the cervical spine. Paraplegia 1979;17:212-21.

6. Sonntag VK. Management of bilateral locked facets of the cervical spine. Neurosurgery 1981;8:150-2.

7. Kleyn PJ. Dislocations of the cervical spine: closed reduction under anaesthesia. Paraplegia 1984;22:271-81.

8. Maiman DJ, Barolat G, Larson SJ. Management of bilateral locked facets of the cervical spine. Neurosurgery 1986;18:542-7.

9. Sabiston CP, Wing PC, Schweigel JF, et al. Closed reduction of dislocations of the lower cervical spine. J Trauma 1988;28:832-5.

10. Ostl OL, Fraser RD, Griffiths ER. Reduction and stabilisation of cervical dislocations. An analysis of 167 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1989;71:275-82.

11. Harrington JF, Likavec MJ, Smith AS. Disc herniation in cervical fracture subluxation. Neurosurgery 1991;29:374-9.

12. Mahale YJ, Silver JR, Henderson NJ. Neurological complications of the reduction of cervical spine dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993;75:403-9.

13. Rizzolo SJ, Vaccaro AR, Cotler JM. Cervical spine trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:2288-98.

14. Robertson PA, Ryan MD. Neurological deterioration after reduction of cervical subluxation. Mechanical compression by disc tissue. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992;74:224-7.

15. Rosenfeld JF, Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ, et al. The benefits of early decompression in cervical spinal cord injury. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1998;27:23-8.

16. Lu K, Lee TC, Chen HJ. Closed reduction of bilateral locked facets of the cervical spine under general anaesthesia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140:1055-61.

17. Farmer J, Vaccaro A, Albert TJ, et al. Neurologic deterioration after cervical spinal cord injury. J Spinal Disord 1998;11:192-6.

18. Vital JM, Gille O, S├®n├®gas J, et al. Reduction technique for uni- and biarticular dislocations of the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:949-54. discussion 955.

19. Fehlings MG, Tator CH. An evidence-based review of decompressive surgery in acute spinal cord injury: rationale, indications, and timing based on experimental and clinical studies. J Neurosurg 1999;91(1 Suppl):1-11.

20. Grant GA, Mirza SK, Chapman JR, et al. Risk of early closed reduction in cervical spine subluxation injuries. J Neurosurg 1999;90(1 Suppl):13-8.

21. Vaccaro AR, Falatyn SP, Flanders AE, et al. Magnetic resonance evaluation of the intervertebral disc, spinal ligaments, and spinal cord before and after closed traction reduction of cervical spine dislocations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:1210-7.

22. OŌĆÖConnor PA, McCormack O, No├½l J, et al. Anterior displacement correlates with neurological impairment in cervical facet dislocations. Int Orthop 2003;27:190-3.

23. Greg Anderson D, Voets C, Ropiak R, et al. Analysis of patient variables affecting neurologic outcome after traumatic cervical facet dislocation. Spine J 2004;4:506-12.

24. Tumial├Īn LM, Dadashev V, Laborde DV, et al. Management of traumatic cervical spondyloptosis in a neurologically intact patient: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:E703-8.

25. Miao DC, Qi C, Wang F, et al. Management of severe lower cervical facet dislocation without vertebral body fracture using skull traction and an anterior approach. Med Sci Monit 2018;24:1295-302.

26. Nockels RP. Nonoperative management of acute spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(24 Suppl):S31-7.

27. Reindl R, Ouellet J, Harvey EJ, et al. Anterior reduction for cervical spine dislocation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:648-52.

28. Del Curto D, Tamaoki MJ, Martins DE, et al. Surgical approaches for cervical spine facet dislocations in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014:CD008129.

29. Lee AS, MacLean JC, Newton DA. Rapid traction for reduction of cervical spine dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994;76:352-6.

30. Eismont FJ, Arena MJ, Green BA. Extrusion of an intervertebral disc associated with traumatic subluxation or dislocation of cervical facets. Case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991;73:1555-60.

31. Xiong XH, Bean A, Anthony A, et al. Manipulation for cervical spinal dislocation under general anaesthesia: serial review for 4 years. Spinal Cord 1998;36:21-4.

32. Doran SE, Papadopoulos SM, Ducker TB, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging documentation of coexistent traumatic locked facets of the cervical spine and disc herniation. J Neurosurg 1993;79:341-5.

33. Rizzolo SJ, Piazza MR, Cotler JM, et al. Intervertebral disc injury complicating cervical spine trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16(6 Suppl):S187-9.

34. Darsaut TE, Ashforth R, Bhargava R, et al. A pilot study of magnetic resonance imaging-guided closed reduction of cervical spine fractures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:2085-90.

35. Hart RA. Cervical facet dislocation: when is magnetic resonance imaging indicated? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:116-7.

36. Carlson GD, Minato Y, Okada A, et al. Early time-dependent decompression for spinal cord injury: vascular mechanisms of recovery. J Neurotrauma 1997;14:951-62.

37. Olerud C, J├│nsson H Jr. Compression of the cervical spine cord after reduction of fracture dislocations. Report of 2 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1991;62:599-601.

38. Star AM, Jones AA, Cotler JM, et al. Immediate closed reduction of cervical spine dislocations using traction. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990;15:1068-72.

39. Zileli M, Osorio-Fonseca E, Konovalov N, et al. Early management of cervical spine trauma: WFNS Spine Committee Recommendations. Neurospine 2020;17:710-22.

40. Vaccaro AR, Koerner JD, Radcliff KE, et al. AOSpine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system. Eur Spine J 2016;25:2173-84.

41. Wimberley DW, Vaccaro AR, Goyal N, et al. Acute quadriplegia following closed traction reduction of a cervical facet dislocation in the setting of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:E433-8.

42. Khezri N, Ailon T, Kwon BK. Treatment of facet injuries in the cervical spine. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2017;28:125-37.

43. Lambiris E, Zouboulis P, Tyllianakis M, et al. Anterior surgery for unstable lower cervical spine injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;(411):61-9.

44. Dvorak MF, Fisher CG, Aarabi B, et al. Clinical outcomes of 90 isolated unilateral facet fractures, subluxations, and dislocations treated surgically and nonoperatively. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:3007-13.

45. Zhou F, Zou J, Gan M, et al. Management of fracture-dislocation of the lower cervical spine with the cervical pedicle screw system. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:406-10.

46. Lee JY, Nassr A, Eck JC, et al. Controversies in the treatment of cervical spine dislocations. Spine J 2009;9:418-23.

47. Kanna RM, Shetty AP, Rajasekaran S. Modified anterioronly reduction and fixation for traumatic cervical facet dislocation (AO type C injuries). Eur Spine J 2018;27:1447-53.

48. de Oliveira JC. Anterior plate fixation of traumatic lesions of the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987;12:324-9.

49. Cloward RB. Reduction of traumatic dislocation of the cervical spine with locked facets. Technical note. J Neurosurg 1973;38:527-31.

50. de Oliveira JC. Anterior reduction of interlocking facets in the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1979;4:195-202.

51. Ebraheim NA, DeTroye RJ, Rupp RE, et al. Osteosynthesis of the cervical spine with an anterior plate. Orthopedics 1995;18:141-7.

52. Lowery GL, McDonough RF. The significance of hardware failure in anterior cervical plate fixation. Patients with 2- to 7-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:181-6. discussion 186-7.