INTRODUCTION

Basilar invagination is a congenital malformation due to abnormal development of the craniocervical junction area, causing compression of medulla and spinal cord, resulting in several neurological symptoms. There are few studies for basilar invagination without atlantoaxial dislocation (type B basilar invagination), and surgical treatment remains controversial [

1,

2]. Since the vertical dislocation and retroversion of odontoid in type B basilar invagination have not been the focus of previous studies, the surgical modalities used in previous studies mainly include foramen magnum decompression (FMD) and transoral odontoidectomy [

3,

4]. However, FMD can only achieve effective decompression of the dorsal side of spinal cord, meanwhile, threaten the stability of craniovertebral junction (CVJ) area. Transoral or transnasal surgeries are associated with a higher risk of postoperative complications such as infection or aspiration. In our previous study, we introduced the intra-articular C1–2 facet distraction, fixation, and cantilever reduction technique for basilar invagination with atlantoaxial dislocation (type A basilar invagination) in which lateral joints were distracted, fusion cages were implanted, and satisfactory reduction of basilar invagination and clinical results were achieved [

5,

6]. In this study, we proposed the use of this technique for treating type B basilar invagination, and reported the results and surgical indications for this procedure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study, approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (LYS[2021]021). Each patient signed an informed consent form for participation in this study.

This study enrolled consecutive type B basilar invagination patients who underwent surgical treatment at Xuanwu Hospital between March 2017 and December 2021. Surgical treatment including intra-articular C1–2 facet distraction, fixation, cantilever reduction surgery, and FMD. Decisions about operation method based on patients’ willingness. Before the operation, attending doctors thoroughly explained the effectiveness and safety of both operations to the patients. After signing the informed consent form, patients were asked to decide freely. Thereafter, the patients were divided into the experimental group (underwent intra-articular C1–2 facet distraction, fixation, and cantilever reduction surgery) and the control group (underwent FMD) according to the chosen surgical procedure.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) suffering from basilar invagination, (2) not combined with atlantoaxial dislocation, and (3) significant clinical symptoms. The exclusion criteria were: (1) local inflammation such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, (2) os odontoideum, (3) trauma at the craniocervical junction area, (4) osteoporosis, (5) tumor involving craniocervical junction area, or (6) severe basic disease. Basilar invagination was diagnosed when the tip of the odontoid was > 5 mm above Chamberlain’s line, and atlantoaxial dislocation was defined as ADI > 3 mm.

2. Surgical Procedures

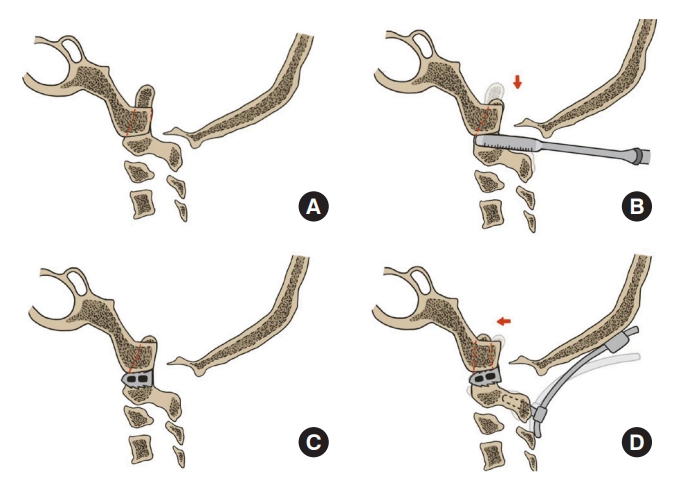

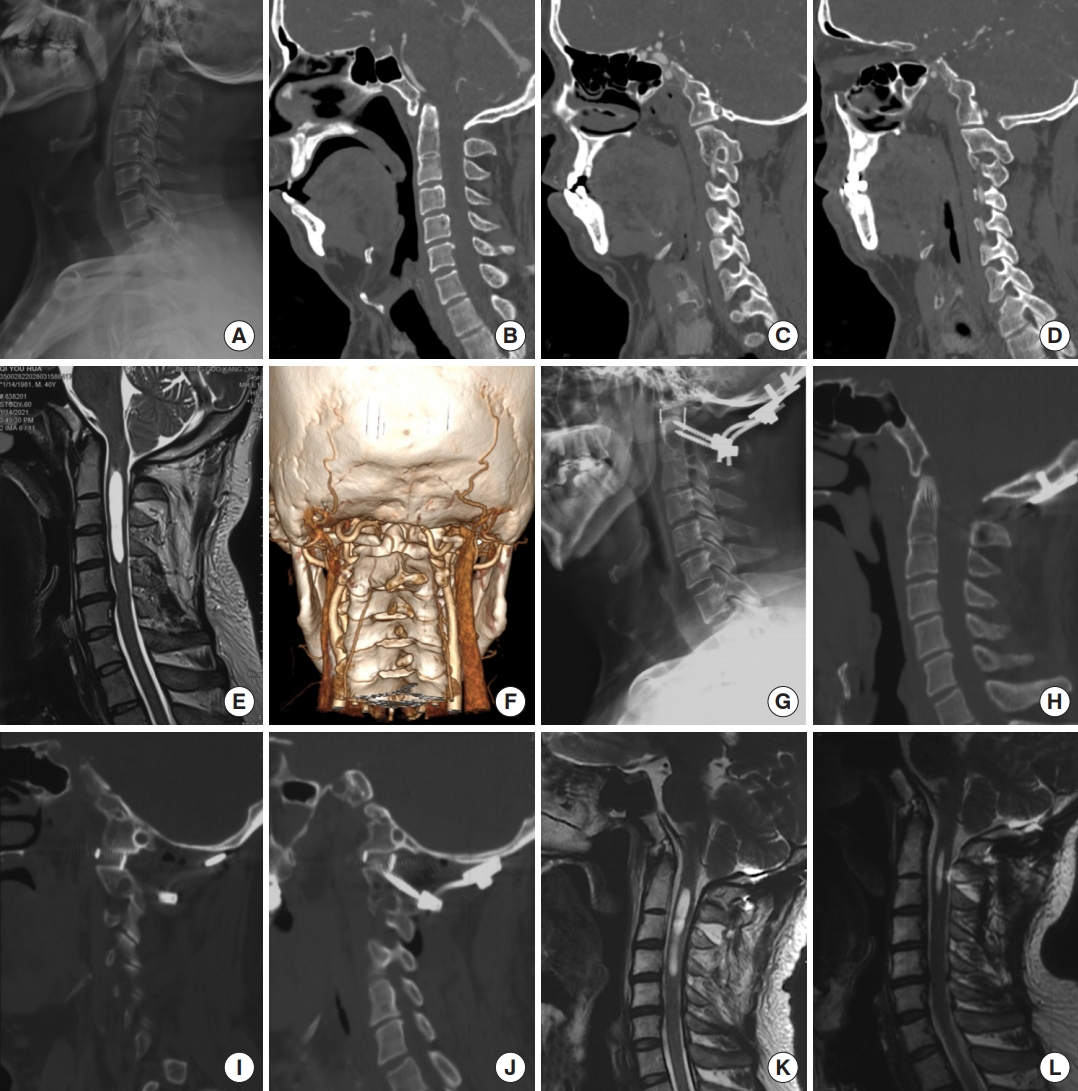

Posterior intra-articular C1–2 facet distraction, fixation, and cantilever reduction surgery: The patient was placed in a prone position after general anesthesia, with neck slightly extended. Cervical traction was applied with one-sixth of body weight (up to 18 kg) and maintained intraoperatively. A posterior median incision was made. After subperiosteal dissection, the C2 nerve root and venous plexus were dissected, and the lateral joint was exposed. A 2-mm bone chisel was inserted into the joint capsule to completely remove the articular cartilage. Thereafter, individual intra-articular distractors were inserted into the joints with rotation. The joint space was opened with the sequential increase in the size of distractors. After distraction on one side, an appropriate distractor trail was placed in the joint to maintain the gap and then distraction in the contralateral joint space was performed. These steps were repeated on both sides until basilar invagination was reduced to the planned position (based on the distance from the odontoid to Chamberlain’s line). Thereafter, the cages filled with autologous iliac bone were placed into the bilateral joints and intraoperative fluoroscopy was performed to confirm their position, height of cages (design height 6–9 mm) were determined by the severity of basilar invagination and intra-articular release (

Figs. 1,

2).

Occipital condyle screws or occipital plates were placed parallel to the external occipital protuberance (external occipital crest) using midline screws, and then pedicle screws were placed into C2 pedicles. The titanium rods were bent to match the contour of the occipital cervical junction and first fixed caudally to the C2 pedicle screws. The cranial ends of the rods were then pressed into occipital screws using cantilever technique, and the rods were pushed in by screw rotation, driving the C2 vertebrae to move and tilt ventrally, thereby increasing the lordosis between the atlantoaxial vertebrae, improving cervicomedullary angle (CMA), allowing further decompression of the vertebral body. The screws were tightened and tabs were removed after reduction of the basilar invagination was confirmed using the O-arm (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland).

Foramen magnum decompression: The patient was placed in a prone position after general anesthesia, with head fixed in a pin headholder, and neck slightly flexed. After sterilizing, a posterior midline incision was made, and the posterior atlantoaxial arch and occipital scales were revealed. Then the posterior atlantoaxial arch, the posterior border of foramen magnum, and part of the squama were removed, and the transition between cerebellar hemisphere and spinal dura was visible. The posterior atlanto-occipital fascia was cut out, and the muscle, fascia, and skin were tightly sutured in layers after extensive irrigation.

3. Clinical and Radiographic Assessments

We analyzed the preoperative and postoperative examination results and clinical scores of all patients. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations were scheduled within one week and at 3, 6, 12 months postoperatively. The effect of reduction, decompression were analyzed by measuring the distance from the odontoid tip to Chamberlain’s line (DCL), clivus-canal angle (CCA), CMA, CVJ triangle area [

7], width of subarachnoid space, and width of syrinx (if present). Patients’ clinical outcomes were assessed by symptom changes, Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score, and 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) score preoperatively, postoperatively, and every 6 months postoperatively (

Fig. 3).

4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 26.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The independent-samples t-test was used to analyze any statistical difference between the 2 groups, and paired-samples t-test was used to analyze any statistical difference between the preoperative and postoperative measurements. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation unless stated otherwise. Cutoff values were calculated by X-tile software [

8].

DISCUSSION

Basilar invagination was first introduced by Anders Adolph Retzius and Frederik Theodor Berg in 1855, mainly caused by congenital bony abnormalities in the craniocervical junction area, such as hypoplasia of clivus, C1 assimilation, odontoid anomalies, or atlantoaxial dislocation [

9-

12]. Goel [

2] proposed a classification of basilar invagination in 2004, wherein type A basilar invagination indicates combined with atlantoaxial dislocation, and type B basilar invagination indicates without atlantoaxial dislocation. Subsequently, they identified that type B basilar invagination was secondary to instability at the atlantoaxial joint, but this theory lacks imaging evidence and remains controversial [

13].

In this study of 54 patients, the average DCL was 11.45 mm, the average CCA was 133.95°, and the average CMA was 140.97°, indicating the main characteristic of type B basilar invagination is vertical dislocation and retroversion of the odontoid, which results in compression of subarachnoid space, medulla, and spinal cord, directly leading to clinical symptoms or syringomyelia. Moreover, significant compression of the ventral aspect of spinal cord was observed in all images.

The treatment of type B basilar invagination remains controversial [

3,

13-

20]. Goel et al. initially introduced FMD to treat type B basilar invagination, but symptoms did not improve significantly after surgery in some studies [

21]. Sangwanloy et al. [

22] suggested that FMD in patients with CCA less than 135° was less effective. Recently, Goel reported treating type B basilar invagination by atlantoaxial fixation, but this method has not been widely accepted due to the lack of pathogenesis evidence, and simple atlantoaxial fixation has no effect on reducing basilar invagination [

14,

23]. Some surgeons used transoral or transnasal odontoidectomy to directly relieve the ventral compression of spinal cord by odontoid, but the stability between atlantoaxial vertebrae is disrupted after odontoidectomy, which may cause atlantoaxial instability and require posterior fixation and fusion. In addition, transoral or transnasal odontoidectomy is more complex, with a higher risk of infection [

3,

17].

Previously, we proposed the use of posterior intra-articular distraction, fixation, and cantilever reduction technique to treat type A basilar invagination, which achieved satisfactory direct decompression and significant relief of symptoms [

5,

24]. We found that distraction of atlantoaxial joints can move the axial caudally, restore CCA by cantilever technique, and effectively reduce basilar invagination. According to this theory, we speculated that this technique would also be effective in treating type B basilar invagination.

We performed posterior interarticular distraction and implanted PEEK fusion cages (6 mm high) successfully in lateral joints in experimental group. DCL improved 3.93±2.49 mm from preoperative, CCA improved 4.92°±3.11° from preoperative, and CMA improved 14.19°±8.43° from preoperative. The width of subarachnoid space, and CVJ triangle area were also significantly improved in these patients. Between the 2 groups, patients in experimental group showed more significant improvements in all radiographic and clinical assessments (

Table 3).

The compression of the spinal cord by odontoid and interatlantoaxial soft tissues cannot be fully reflected by using only bony measurements such as DCL or CCA. The compression of the spinal cord can be directly reflected by measurements in MRI scan. After correlational analyses between radiographic and clinical assessments, we found that SF-12 score improvement was associated with preoperative CVJ triangle area (Pearson index, 0.515; p = 0.004). The larger the preoperative CVJ triangle area, the more significant improvement in SF-12 scores, which suggested that patients with more severe preoperative ventral compression of spinal cord can benefit the most from this technique. By calculating the cutoff values, we concluded that posterior intra-articular distraction, fixation, and cantilever reduction technique should be preferred when the CVJ triangle area is > 2.00 cm

2 (chi-square= 10.11, p = 0.001) (

Fig. 6).

Intraoperative placement of fusion cages in lateral joints and reduction by cantilever technique with cages as fulcrum have following unique advantages in treating type B basilar invagination: (1) It moves odontoid caudally, corrects basilar invagination, and directly reduces the compression of the ventral aspect of spinal cord. (2) It reduces the CCA by rotating axis forward, and further reduces the ventral compression of spinal cord. (3) Fusion cages in joints can act as fulcrums and distribute the stress on posterior internal fixation system, thereby avoiding failure of internal fixation due to stress concentration. (4) Fusion cages between the joints are more aligned with Wolff’s law, the compressive stress between the joint surfaces can accelerate bony fusion, resulting in a higher fusion rate than dorso-lateral bone graft. (5) Compared to transoral odontoidectomy, this technique reduces the incidence of surgical complications.

In patients with basilar invagination caused by platybasia or other skull base developmental abnormalities, the present technique cannot completely reposition the odontoid. Because the anterior atlantoaxial tension band is intact in patients with type B basilar invagination, distracting is more difficult than with type A basilar invagination. For cases that are difficult to distract or have severe atlantoaxial deformity, transoral or transnasal odontoidectomy and posterior decompression surgery may be necessary to relieve the spinal cord compression. Surgical limitations of this technique may be derived from the following conditions: (1) Relationship between vertebral artery and atlantoaxial joint. (2) Atlantoaxial articular space blocked by the occiput. (3) Collapse of the articular surface. Therefore, preoperative CTA and CT reconstruction examinations are necessary to clarify the individual anatomy of the CVJ area. Moreover, a bone density test is required for elderly patients to reduce the risk of joint surface collapse.

Constrained by research conditions, it was difficult to conduct a randomized study, so decisions on surgical method were made according to patients' willingness, which may import inherent biases. Fortunately, there was no statistical difference at baseline, indicating that this bias was relatively small. Ideally, a prospective randomized study should be undertaken, providing high level evidence to the treatment of type B basilar invagination.